Werner Eduard Fritz von Blomberg (2 September 1878 – 13 March 1946) was a German general and politician who served as the first Minister of War in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1938. Blomberg had served as Chief of the Truppenamt, equivalent to the German General Staff, during the Weimar Republic from 1927 to 1929.

Blomberg served on the Western Front during World War I and rose through the ranks of the Reichswehr until he was appointed chief of the Truppenamt. Despite being dismissed from the Truppenamt, he was later appointed Defence Minister by President Paul von Hindenburg in January 1933.

Following the Nazis’ rise to power in Germany, Blomberg was named Minister of War and Commander-in-Chief of the German Armed Forces. In this capacity, he played a central role in Germany’s rearmament as well as purging the military of dissidents to the new regime. However, as Blomberg grew increasingly critical of the Nazis’ foreign policy, he was ultimately forced to resign in the Blomberg-Fritsch affair in 1938 orchestrated by his political rivals, Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler. Thereafter, Blomberg spent World War II in obscurity until he served as a witness in the Nuremberg trials shortly before his death.

Early life and career

Werner Eduard Fritz von Blomberg was born on 2 September 1878 in Stargard, Province of Pomerania (now Stargard, Poland) into a noble Baltic German family. Blomberg joined the Prussian Army in 1897 and attended the Prussian Military Academy from 1904 to 1908. Blomberg entered the German General Staff in 1908 and served as a staff officer with distinction on the Western Front during the First World War. He participated in the First Battle of the Marne in 1914 and the Battle of Verdun in 1916. Blomberg was awarded the Pour le Mérite.

Blomberg married Charlotte Hellmich in April 1904. The couple had five children.

In 1920, Blomberg was appointed chief of staff of the Döberitz Brigade; in 1921, he was appointed chief of staff of the Stuttgart Army Area. In 1925, General Hans von Seeckt appointed him chief of army training. By 1927, Blomberg was a major-general and chief of the Troop Office (German: Truppenamt), the thin disguise for the German General Staff, which had been forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles.

In the Weimar Republic

In 1928, Blomberg visited the Soviet Union, where he was much impressed by the high status of the Red Army, and left a convinced believer in the value of totalitarian dictatorship as the prerequisite for military power.

This was part of a broader shift on the part of the German military to the idea of a totalitarian Wehrstaat (transl. Defence State) which, beginning in the mid-1920s, became increasingly popular with military officers. The German historian Eberhard Kolb wrote that:

from the mid-1920s onwards the Army leaders had developed and propagated new social conceptions of a militarist kind, tending towards a fusion of the military and civilian sectors and ultimately a totalitarian military state (Wehrstaat).

Blomberg’s visit to the Soviet Union in 1928 confirmed his view that totalitarian power fosters the greatest military power. Blomberg believed the next world war, as the previous one, would become a total war, requiring full mobilization of German society and economy by the state, and that a totalitarian state would best prepare society in peacetime, militarily and economically, for war. As most of Nazi Germany’s military elite, Blomberg took for granted that, for Germany to achieve the world power that it had unsuccessfully sought in the First World War would require another war, and that such a war would be total war of a highly mechanized, industrial type.

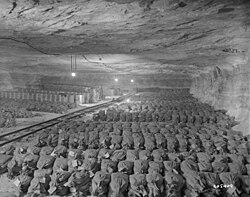

In 1929, Blomberg came into conflict with General Kurt von Schleicher at the Truppenamt and was removed from his post and appointed military commander in East Prussia. Early that year, Schleicher had started a policy of “frontier defense” (Grenzschutz) under which the Reichswehr would stockpile arms in secret depots and begin training volunteers beyond the limits imposed by the Treaty of Versailles in the eastern parts of Germany bordering Poland; in order to avoid incidents with France, there was to be no such Grenzschutz in western Germany.

The French planned to withdraw from the Rhineland in June 1930 – five years earlier than specified by the Treaty of Versailles – and Schleicher wanted no violations of the Treaty that might seem to threaten France before French troops left the Rhineland. When Blomberg, whom Schleicher personally disliked, insisted on extending Grenzschutz to areas bordering France, Schleicher in August 1929 leaked to the press that Blomberg had attended armed maneuvers by volunteers in Westphalia. Defence Minister General Wilhelm Groener called Blomberg to Berlin to explain himself. Blomberg expected Schleicher to stick to the traditional Reichswehr policy of denying everything, and was shocked to see Schleicher instead attack him in front of Groener as a man who had recklessly exposed Germany to the risk of providing the French with an excuse to remain in the Rhineland until 1935.

As a result, Blomberg was demoted from command of the Truppenamt and sent to command a division in East Prussia. Since East Prussia was cut off from the rest of Germany and had only one infantry division stationed there, Blomberg—to increase the number of fighting men in the event of a war with Poland—started to make lists of all the men fit for military service, which further increased the attraction of a totalitarian state able to mobilize an entire society for war to him, and of an ideologically motivated levée en masse as the best way to fight the next war. During his time as commander of Wehrkreis I, the military district which comprised East Prussia, Blomberg fell under the influence of a Nazi-sympathizing Lutheran chaplain, Ludwig Müller, who introduced Blomberg to Nazism. Blomberg cared little for Nazi doctrines per se, his support for the Nazis being motivated by his belief that only a dictatorship could make Germany a great military power again, and that the Nazis were the best party to establish a dictatorship in Germany.

Because he had the command of only one infantry division in East Prussia, Blomberg depended very strongly on Grenzschutz to increase the number of fighting men available. This led him to co-operate closely with the SA as a source of volunteers for Grenzschutz forces. Blomberg had excellent relations with the SA at this time, which led to the SA serving by 1931 as an unofficial militia backing up the Reichswehr. Many generals saw East Prussia as a model for future Army-Nazi co-operation all over Germany.

Blomberg’s interactions with the SA in East Prussia led him to the conclusion that Nazis made for excellent soldiers, which further increased the appeal of Nazism for him. But at the same time, Blomberg saw the SA only as a junior partner to the Army, and utterly opposed the SA’s ambitions to replace the Reichswehr as Germany’s main military force. Blomberg, like almost all German generals, envisioned a future Nazi-Army relationship where the Nazis would indoctrinate ordinary people with the right sort of ultra-nationalist, militarist values so that when young German men joined the Reichswehr they would be already half-converted into soldiers while at the same time making it clear that control of military matters would rest solely with the generals. In 1931, he visited the US, where he openly proclaimed his belief in the certainty and the benefits of a Nazi government for Germany. Blomberg’s first wife Charlotte died on 11 May 1932, leaving him with two sons and three daughters.

In 1932, Blomberg served as part of the German delegation to the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva where, during his time as the German chief military delegate, he not only continued his pro-Nazi remarks to the press, but used his status as Germany’s chief military delegate to communicate his views to Paul von Hindenburg, whose position as President of Germany made him German Supreme Commander in Chief.

In his reports to Hindenburg, Blomberg wrote that his arch-rival Schleicher’s attempts to create the Wehrstaat had clearly failed, and that Germany needed a new approach to forming the Wehrstaat. By late January 1933, it was clear that the Schleicher government could only stay in power by proclaiming martial law and by authorizing the Reichswehr to crush popular opposition. In doing so, the military would have to kill hundreds, if not thousands of German civilians; any régime established in this way could never expect to build the national consensus necessary to create the Wehrstaat. The military had decided that Hitler alone was capable of peacefully creating the national consensus that would allow the creation of the Wehrstaat, and thus the military successfully brought pressure on Hindenburg to appoint Hitler as Chancellor.

In late January 1933, President Hindenburg—without informing the chancellor, Schleicher, or the army commander, General Kurt von Hammerstein—recalled Blomberg from the World Disarmament Conference to return to Berlin. Upon learning of this, Schleicher guessed correctly that the order to recall Blomberg to Berlin meant his own government was doomed. When Blomberg arrived at the railroad station in Berlin on 28 January 1933, he was met by two officers, Adolf-Friedrich Kuntzen and Oskar von Hindenburg, adjutant and son of President Hindenburg. Kuntzen had orders from Hammerstein for Blomberg to report at once to the Defense Ministry, while Oskar von Hindenburg had orders for Blomberg to report directly to the Palace of the Reich President.

Over and despite Kuntzen’s protests, Blomberg chose to go with Hindenburg to meet the president, who swore him in as defense minister. This was done in a manner contrary to the Weimar constitution, under which the president could only swear in a minister after receiving the advice of the chancellor. Hindenburg had not consulted Schleicher about his wish to see Blomberg replace him as defense minister because in late January 1933, there were wild (and untrue) rumors circulating in Berlin that Schleicher was planning to stage a putsch. To counter alleged plans of a putsch by Schleicher, Hindenburg wanted to remove Schleicher as defense minister as soon as possible.

Two days later, on 30 January 1933, Hindenburg swore in Adolf Hitler as Chancellor, after telling him that Blomberg was to be his defense minister regardless of his wishes. Hitler for his part welcomed and accepted Blomberg.

Minister of Defense

In 1933, Blomberg rose to national prominence when he was appointed Minister of Defense in Hitler’s government. Blomberg became one of Hitler’s most devoted followers and worked feverishly to expand the size and the power of the army. Blomberg was made a colonel general for his services in 1933. Although Blomberg and his predecessor, Kurt von Schleicher, loathed each other, their feud was purely personal, not political, and in all essentials, Blomberg and Schleicher had identical views on foreign and defense policies. Their dispute was simply over who was best qualified to carry out the policies, not the policies themselves.

Blomberg was chosen personally by Hindenburg as a man he trusted to safeguard the interests of the Defense Ministry and could be expected to work well with Hitler. Above all, Hindenburg saw Blomberg as a man who would safeguard the German military’s traditional “state within the state” status dating back to Prussian times under which the military did not take orders from the civilian government, headed by the chancellor, but co-existed as an equal alongside the civilian government because of its allegiance only to the head of state, not the chancellor, who was the head of government. Until 1918, the head of state had been the emperor, and since 1925, it had been Hindenburg himself. Defending the military “state within the state” and trying to reconcile the military to the Nazis was to be one of Blomberg’s major concerns as a defense minister.

Blomberg was an ardent supporter of the Nazi regime and cooperated with it in many capacities, including serving on the Academy for German Law. On 20 July 1933, Blomberg had a new Army Law passed, which ended the jurisdiction of civil courts over the military and extinguished the theoretical right for the military to elect councils, although that right, despite being guaranteed by the Weimar Constitution in 1919, had never been put into practice.

Blomberg’s first act as defense minister was to carry out a purge of the officers associated with his hated archenemy, Schleicher. Blomberg sacked Ferdinand von Bredow as chief of the Ministeramt and replaced him with General Walter von Reichenau, Eugen Ott was dismissed as chief of the Wehramt and sent to Japan as a military attaché and General Wilhelm Adam was sacked as chief of the Truppenamt (the disguised General Staff) and replaced with Ludwig Beck. The British historian Sir John Wheeler-Bennett wrote about the “ruthless” way that Blomberg set about isolating and undermining the power of the army commander-in-chief, a close associate of Schleicher, General Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, to the point that in February 1934 Hammerstein finally resigned in despair, as his powers had become more nominal than real. With Hammerstein’s resignation, the entire Schleicher faction that had dominated the army since 1926 had been removed from their positions within the High Command. Wheeler-Bennett commented that as a military politician Blomberg was every bit as ruthless as Schleicher had been. The resignation of Hammerstein caused a crisis in military-civil relations when Hitler attempted to appoint as his successor Reichenau, a man who was not acceptable to the majority of the Reichswehr. Blomberg supported the attempt to appoint Reichenau, but reflecting the power of the “state within the state”, certain Army officers appealed to Hindenburg, which led to Werner von Fritsch being appointed instead.

Far more serious than dealing with the followers of Schleicher was Blomberg’s relations with the SA. He was resolutely opposed to any effort to subject the military to the control of the Nazi Party or that of any of its affiliated organizations such as the SA or the SS, and throughout his time as a minister, he fought fiercely to protect the institutional autonomy of the military.

By the autumn of 1933, Blomberg had come into conflict with Ernst Röhm, who made it clear that he wanted to see the SA absorb the Reichswehr, a prospect that Blomberg was determined to prevent at all costs. In December 1933, he made clear to Hitler his displeasure about Röhm being appointed to the Cabinet. In February 1934, when Röhm penned a memo about the SA absorbing the Reichswehr to become the new military force, Blomberg informed Hitler that the Army would never accept it under any conditions. On 28 February 1934, Hitler ruled the Reichswehr would be the main military force, and the SA was to remain a political organization. Despite the ruling, Röhm continued to press for a greater role for the SA. In March 1934, Blomberg and Röhm began openly fighting each other at cabinet meetings and exchanging insults and threats. As a result of his increasingly-heated feud with Röhm, Blomberg warned Hitler that he must curb the ambitions of the SA, or the Army would do so itself.

To defend the military “state within the state”, Blomberg followed a strategy of Nazifying the military more and more in a paradoxical effort to persuade Hitler that it was not necessary to end the traditional “state within the state” to prevent Gleichschaltung being imposed by engaging in what can be called a process of “self-Gleichschaltung”.

In February 1934, Blomberg, on his own initiative, had all of the men considered to be Jews serving in the Reichswehr given an automatic and immediate dishonorable discharge. As a result, 74 soldiers lost their jobs for having “Jewish blood”. The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, enacted in April 1933, had excluded Jews who were First World War veterans and did not apply to the military. Thereby, Blomberg’s discharge order was his way of circumventing the law and went beyond what even the Nazis then wanted. The German historian Wolfram Wette called the order “an act of proactive obedience”.

The German historian Klaus-Jürgen Müller [de] wrote that Blomberg’s anti-Semitic purge in early 1934 was part of his increasingly-savage feud with Röhm, who since the summer of 1933 had been drawing unfavorable comparisons between the “racial purity” of his SA, which had no members with “Jewish” blood, and the Reichswehr, which had some. Müller wrote that Blomberg wanted to show Hitler that the Reichswehr was even more loyal and ideologically sound than was the SA and that purging Reichswehr members who could be considered Jewish without being ordered to do so was an excellent way to demonstrate loyalty within the Nazi regime. As both the Army and the Navy had longstanding policies of refusing to accept Jews, there were no Jews to purge within the military. Instead, Blomberg used the Nazi racial definition of a Jew in his purge. None of the men given dishonorable discharges themselves practiced Judaism, but they were the sons or grandsons of Jews who had converted to Christianity and thus were considered to be “racially” Jewish.

Blomberg ordered every member of the Reichswehr to submit documents to their officers and that anyone who was a “non-Aryan” or refused to submit documents would be dishonorably discharged. As a result, seven officers, eight officer cadets, 13 NCOs and 28 privates from the Army, and three officers, four officer candidates, three NCOs and four sailors from the Navy were dishonorably discharged, together with four civilian employees of the Defense Ministry. With the exception of Erich von Manstein, who complained that Blomberg had ruined the careers of 70 men for something that was not their fault, there were no objections.Again, on his own initiative as part of “self-Gleichschaltung”, Blomberg had the Reichswehr in May 1934 adopt Nazi symbols into their uniforms. In 1935, Blomberg worked hard to ensure that the Wehrmacht complied with the Nuremberg Laws by preventing any so-called Mischling from serving.

Blomberg had a reputation as something of a lackey to Hitler. As such, he was nicknamed “Rubber Lion” by some of his critics in the army who were less than enthusiastic about Hitler.[1] One of the few notable exceptions was during the run-up to the Night of the Long Knives from 30 June to 2 July 1934. In early June, Hindenburg decided that unless Hitler did something to end the growing political tension in Germany, he would declare martial law and turn over control of the government to the army. Blomberg, who had been known to oppose the growing power of the SA, was chosen to inform Hitler of that decision on the president’s behalf. When Hitler arrived at Hindenburg’s estate at Neudeck on 21 June 1934, he was greeted by Blomberg on the steps leading into the estate. Wheeler-Bennett wrote that Hitler was faced with “a von Blomberg no longer the affable ‘Rubber Lion’ or the adoring ‘Hitler-Junge Quex‘, but embodying all the stern ruthlessness of the Prussian military caste”.

Blomberg bluntly informed Hitler that Hindenburg was highly displeased with the recent developments and was seriously considering dismissing Hitler as chancellor if he did not rein in the SA at once. When Hitler met Hindenburg, the latter insisted for Blomberg to attend the meeting as a sign of his confidence in the Defense Minister. The meeting lasted half-an-hour, and Hindenburg repeated the threat to dismiss Hitler.

Blomberg was aware of least in general of the purge that Hitler began planning after the Neudeck meeting. The conversations between Blomberg and Hitler in late June 1934 were generally not recorded, which makes it difficult to determine how much Blomberg knew, but he was definitely aware of what Hitler had decided to do. On 25 June 1934, the military was placed in a state of alert, and on 28 June, Röhm was expelled from the League of German Officers.[41] The decision to expel Röhm was part of Blomberg’s effort to maintain the “honor” of the German military. Röhm being executed as a traitor from the League would besmirch the honor of the reputation of the League in general. The same thinking later led to those officers involved in the putsch attempt of 20 July 1944 to be dishonorably discharged before they were tried for treason as a way of upholding military “honor.”

Wheeler-Bennett wrote that the fact that Blomberg instigated the expulsion of Röhm from the League just two days before Röhm was arrested on charges of high treason proved he knew what was coming. Röhm had been quite open about his homosexuality ever since he had been outed in 1925 after the publication in a newspaper of his love letters to a former boyfriend. Wheeler-Bennett found highly implausible Blomberg’s claim that a homosexual would not be allowed to be a member of the League of German Officers. On 29 June 1934, an article by Blomberg appeared in the official newspaper of the Nazi Party, the Völkischer Beobachter, stating that the military was behind Hitler and would support him whatever he did.

In the same year, after Hindenburg’s death on 2 August, as part of his “self-Gleichschaltung” strategy, Blomberg personally ordered all soldiers in the army and all sailors in the Navy to pledge the oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler[44][page needed] not to People and Fatherland but to the new Führer, which is thought to have limited later opposition to Hitler. The oath was the initiative of Blomberg and the Ministeramt chief General Walther von Reichenau. The entire military took the oath to Hitler, who was most surprised at the offer. Thus, the popular view that Hitler imposed the oath on the military is incorrect.

On the other hand, Hitler had long expected Hindenburg’s death and had planned on taking power anyhow and so could he have very well convinced von Blomberg to implement such an oath long before the actual implementation took place.

The intention of Blomberg and Reichenau in having the military swear an oath to Hitler was to create a personal special bond between Hitler and the military, which was intended to tie Hitler more tightly towards the military and away from the Nazi Party. Blomberg later admitted that he had not thought the full implications of the oath at the time. As part of his defense of the military “state within the state”, Blomberg fought against the attempts of the SS to create a military wing.

Heinrich Himmler repeatedly insisted that the SS needed a military wing to crush any attempt at a communist revolution before Blomberg conceded in the idea, which eventually become the Waffen-SS.Blomberg’s relations with the SS were badly strained in late 1934 to early 1935 when it was discovered that the SS had bugged the offices of the Abwehr chief, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. That led Blomberg to warn Hitler the military would not tolerate being spied upon. In response to Blomberg’s protests, Hitler gave orders that the SS could not spy upon the military, no member of the military could be arrested by the police, and cases of suspected “political unreliability” in the military were to be investigated solely by the military police.

Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and Minister of War

On 21 May 1935, the Ministry of Defense was renamed the Ministry of War (Reichskriegsministerium); Blomberg also was given the title of Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces (Wehrmacht), a title no other German officer had ever held. Hitler remained the Supreme Commander of the military in his capacity as Head of State, the Führer of Germany. On 20 April 1936, the loyal Blomberg became the first Generalfeldmarschall appointed by Hitler. On 30 January 1937 to mark the fourth anniversary of the Nazi regime, Hitler personally presented the Golden Party Badge to the remaining non-Nazi members of the cabinet, including Blomberg, and enrolled him in the Party (membership number 3,805,226).

In December 1936, a crisis was created within the German decision-making machinery when General Wilhelm Faupel, the chief German officer in Spain, started to demand the dispatch of three German divisions to fight in the Spanish Civil War as the only way for victory. That was strongly opposed by the Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin von Neurath, who wanted to limit the German involvement in Spain.

At a conference held at the Reich Chancellery on 21 December 1936 attended by Hitler, Hermann Göring, Blomberg, Neurath, General Werner von Fritsch, General Walter Warlimont and Faupel, Blomberg argued against Faupel that an all-out German drive for victory in Spain would be too likely to cause a general war before Germany had rearmed properly. He stated that even if otherwise, it would consume money better spent on military modernization. Blomberg prevailed against Faupel.

Unfortunately for Blomberg, his position as the ranking officer of Nazi Germany alienated Hermann Göring, Hitler’s second-in-command and Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe, Germany’s air force, and Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, the security organization of the Nazi Party, and concurrently the chief of all police forces of Germany, who conspired to oust him from power. Göring, in particular, had ambitions of becoming Commander-in-Chief himself of the entire military.

On 5 November 1937, the conference between the Reich’s top military–foreign policy leadership and Hitler recorded in the so-called Hossbach Memorandum occurred. At the conference, Hitler stated that it was the time for war or, more accurately wars, as what Hitler envisioned would be a series of localized wars in Central and Eastern Europe in the near future. Hitler argued that because the wars were necessary to provide Germany with Lebensraum, autarky and the arms race with France and the United Kingdom made it imperative to act before the Western powers developed an insurmountable lead in the arms race.

Of those invited to the conference, objections arose from Foreign Minister Konstantin von Neurath, Blomberg and the Army Commander-in-Chief, General Werner von Fritsch, that any German aggression in Eastern Europe was bound to trigger a war against France because of the French alliance system in Eastern Europe, the so-called cordon sanitaire, and if a Franco–German war broke out, Britain was almost certain to intervene rather than risk the prospect of France’s defeat. Moreover, it was objected that Hitler’s assumption was flawed that Britain and France would just ignore the projected wars because they had started their rearmament later than Germany had.

Accordingly, Fritsch, Blomberg and Neurath advised Hitler to wait until Germany had more time to rearm before pursuing a high-risk strategy of localized wars that was likely to trigger a general war before Germany was ready. None of those present at the conference had any moral objections to Hitler’s strategy with which they basically agreed; only the question of timing divided them.

Scandal and downfall

Main article: Blomberg–Fritsch affair

Göring and Himmler found an opportunity to strike against Blomberg in January 1938, when the 59-year-old general married his second wife, Erna Gruhn (1913–1978, sometimes referred to as “Eva” or “Margarete”). Blomberg had been a widower since the death of his first wife, Charlotte, in 1932. Gruhn was a 24-year-old typist and secretary, but the Berlin police had a long criminal file on her and her mother, a former prostitute. Among the reports was information that Erna Gruhn had posed for pornographic photos around Christmas 1931,and had been accused by a customer of stealing his gold watch in December 1934.

This information was reported to the Berlin police chief, Wolf-Heinrich von Helldorf, who went to Wilhelm Keitel with the file on the new Mrs. Blomberg. Helldorff said he was uncertain about what to do. Keitel told Helldorf to take the file to Göring, which he did.

Göring, who had served as best man to Blomberg at the wedding, used the file to argue Blomberg was unfit to serve as a war minister. Göring then informed Hitler, who had been present at the wedding. Hitler ordered Blomberg to annul the marriage to avoid a scandal and to preserve the integrity of the army. The upcoming wedding of one of Blomberg’s daughters, Dorothea, would have been threatened by scandal. She was engaged to Karl-Heinz Keitel, the eldest son of Wilhelm Keitel. Blomberg refused to end his marriage but when Göring threatened to make public the pasts of Erna Gruhn and her mother, Blomberg was forced to resign his posts to prevent that, which he did on 27 January 1938. His daughter was married in May the same year.

Keitel, who would be promoted to the rank of field marshal in 1940, and Blomberg’s former right-hand man would be appointed by Hitler as the Chief of the OKW of the Armed Forces.

A few days later, Göring and Himmler accused Generaloberst Werner von Fritsch, the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, of being a homosexual. Hitler used these opportunities for a major reorganization of the Wehrmacht. Fritsch was later acquitted; together, the events became known as the Blomberg–Fritsch Affair.

Generalfeldmarschall von Blomberg and his wife went on a honeymoon for a year to the island of Capri. Admiral Erich Raeder decided that Blomberg needed to commit suicide to atone for his marriage, and dispatched an officer to Italy, who followed the Blombergs around on their honeymoon and persistently and unsuccessfully tried to force Blomberg to commit suicide. The officer at one point even tried to force a gun into Blomberg’s hands, but he declined to end his life. Spending World War II in obscurity, Blomberg was arrested by the Allies in 1945 and later gave evidence at the Nuremberg trials.

Imprisonment and death

Blomberg’s health declined rapidly while he was in detention at Nuremberg. He faced the contempt of his former colleagues and the intention of his young wife to abandon him. It is possible that he manifested symptoms of cancer as early as 1939. On 12 October 1945, he noted in his diary that he weighed slightly over 72 kilograms (159 lb). He was diagnosed with colorectal cancer on 20 February 1946. Resigned to his fate and gripped by depression, he spent the final weeks of his life refusing to eat.

Blomberg died on 13 March 1946. His body was buried without ceremony in an unmarked grave. His remains were later cremated and interred in his residence in Bad Wiessee.