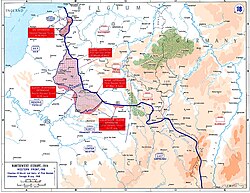

The Western Front was one of the main theatres of war during the First World War. Following the outbreak of war in August 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The German advance was halted with the Battle of the Marne. Following the Race to the Sea, both sides dug in along a meandering line of fortified trenches, stretching from the North Sea to the Swiss frontier with France, the position of which changed little except during early 1917 and again in 1918.

Between 1915 and 1917 there were several offensives along this front. The attacks employed massive artillery bombardments and massed infantry advances. Entrenchments, machine gun emplacements, barbed wire, and artillery repeatedly inflicted severe casualties during attacks and counter-attacks and no significant advances were made. Among the most costly of these offensives were the Battle of Verdun, in 1916, with a combined 700,000 casualties, the Battle of the Somme, also in 1916, with more than a million casualties, and the Battle of Passchendaele, in 1917, with 487,000 casualties.

To break the deadlock of the trench warfare on the Western Front, both sides tried new military technology, including poison gas, aircraft, and tanks. The adoption of better tactics and the cumulative weakening of the armies in the west led to the return of mobility in 1918. The German spring offensive of 1918 was made possible by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that ended the war of the Central Powers against Russia and Romania on the Eastern Front. Using short, intense “hurricane” bombardments and infiltration tactics, the German armies moved nearly 100 kilometres (60 miles) to the west, the deepest advance by either side since 1914, but the result was indecisive.

The unstoppable advance of the Allied armies during the Hundred Days Offensive of 1918 caused a sudden collapse of the German armies and persuaded the German commanders that defeat was inevitable. The German government surrendered in the Armistice of 11 November 1918, and the terms of peace were settled by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

1914

War plans – Battle of the Frontiers

French bayonet charge (1913 photograph)

German infantry on the battlefield, 7 August 1914

The Western Front was the place where the most powerful military forces in Europe, the German and French armies, met and where the First World War was decided. At the outbreak of the war, the German Army, with seven field armies in the west and one in the east, executed a modified version of the Schlieffen Plan, bypassing French defenses along the common border by moving quickly through neutral Belgium, and then turning southwards to attack France and attempt to encircle the French Army and trap it on the German border. Belgian neutrality had been guaranteed by Britain under the Treaty of London, 1839; this caused Britain to join the war at the expiration of its ultimatum at midnight on 4 August. Armies under German generals Alexander von Kluck and Karl von Bülow attacked Belgium on 4 August 1914. Luxembourg had been occupied without opposition on 2 August. The first battle in Belgium was the Battle of Liège, a siege that lasted from 5–16 August. Liège was well fortified and surprised the German Army under Bülow with its level of resistance. German heavy artillery was able to demolish the main forts within a few days. Following the fall of Liège, most of the Belgian field army retreated to Antwerp, leaving the garrison of Namur isolated, with the Belgian capital, Brussels, falling to the Germans on 20 August. Although the German army bypassed Antwerp, it remained a threat to their flank. Another siege followed at Namur, lasting from about 20–23 August.

The French deployed five armies on the frontier. The French Plan XVII was intended to bring about the capture of Alsace–Lorraine. On 7 August, the VII Corps attacked Alsace to capture Mulhouse and Colmar. The main offensive was launched on 14 August with the First and Second Armies attacking toward Sarrebourg-Morhange in Lorraine. In keeping with the Schlieffen Plan, the Germans withdrew slowly while inflicting severe losses upon the French. The French Third and Fourth Armies advanced toward the Saar and attempted to capture Saarburg, attacking Briey and Neufchateau but were repulsed. The French VII Corps captured Mulhouse after a brief engagement first on 7 August, and then again on 23 August, but German reserve forces engaged them in the Battle of Mulhouse and forced the French to retreat twice.

The German Army swept through Belgium, executing civilians and razing villages. The application of “collective responsibility” against a civilian population further galvanised the allies. Newspapers condemned the German invasion, violence against civilians and destruction of property, which became known as the “Rape of Belgium.”After marching through Belgium, Luxembourg and the Ardennes, the Germans advanced into northern France in late August, where they met the French Army, under Joseph Joffre, and the divisions of the British Expeditionary Force under Field Marshal Sir John French. A series of engagements known as the Battle of the Frontiers ensued, which included the Battle of Charleroi and the Battle of Mons. In the former battle the French Fifth Army was almost destroyed by the German 2nd and 3rd Armies and the latter delayed the German advance by a day. A general Allied retreat followed, resulting in more clashes at the Battle of Le Cateau, the Siege of Maubeuge and the Battle of St. Quentin (also called the First Battle of Guise).

First Battle of the Marne

Main article: First Battle of the Marne

The German Army came within 70 km (43 mi) of Paris but at the First Battle of the Marne (6–12 September), French and British troops were able to force a German retreat by exploiting a gap which appeared between the 1st and 2nd Armies, ending the German advance into France. The German Army retreated north of the Aisne and dug in there, establishing the beginnings of a static western front that was to last for the next three years. Following this German retirement, the opposing forces made reciprocal outflanking manoeuvres, known as the Race to the Sea and quickly extended their trench systems from the Swiss frontier to the North Sea. The territory occupied by Germany held 64 percent of French pig-iron production, 24 percent of its steel manufacturing and 40 percent of the coal industry – dealing a serious blow to French industry.

On the Entente side (those countries opposing the German alliance), the final lines were occupied with the armies of each nation defending a part of the front. From the coast in the north, the primary forces were from Belgium, the British Empire and then France. Following the Battle of the Yser in October, the Belgian army controlled a 35 km (22 mi) length of West Flanders along the coast, known as the Yser Front, along the Yser and the Ieperlee from Nieuwpoort to Boezinge.Meanwhile, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) occupied a position on the flank, having occupied a more central position.

First Battle of Ypres

Main article: First Battle of Ypres

From 19 October until 22 November, the German forces made their final breakthrough attempt of 1914 during the First Battle of Ypres, which ended in a mutually-costly stalemate. After the battle, Erich von Falkenhayn judged that it was no longer possible for Germany to win the war by purely military means and on 18 November 1914 he called for a diplomatic solution. The Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg; Generalfeldmarschall Paul von Hindenburg, commanding Ober Ost (Eastern Front high command); and his deputy, Erich Ludendorff, continued to believe that victory was achievable through decisive battles. During the Lodz offensive in Poland (11–25 November), Falkenhayn hoped that the Russians would be made amenable to peace overtures. In his discussions with Bethmann Hollweg, Falkenhayn viewed Germany and Russia as having no insoluble conflict and that the real enemies of Germany were France and Britain. A peace with only a few annexations of territory also seemed possible with France and that with Russia and France out of the war by negotiated settlements, Germany could concentrate on Britain and fight a long war with the resources of Europe at its disposal. Hindenburg and Ludendorff continued to believe that Russia could be defeated by a series of battles which cumulatively would have a decisive effect, after which Germany could finish off France and Britain.

Trench warfare

Main article: Trench warfare

Trench warfare in 1914, while not new, quickly improved and provided a very high degree of defense. According to two prominent historians:Trenches were longer, deeper, and better defended by steel, concrete, and barbed wire than ever before. They were far stronger and more effective than chains of forts, for they formed a continuous network, sometimes with four or five parallel lines linked by interfacings. They were dug far below the surface of the earth out of reach of the heaviest artillery…. Grand battles with the old maneuvers were out of the question. Only by bombardment, sapping, and assault could the enemy be shaken, and such operations had to be conducted on an immense scale to produce appreciable results. Indeed, it is questionable whether the German lines in France could ever have been broken if the Germans had not wasted their resources in unsuccessful assaults, and the blockade by sea had not gradually cut off their supplies. In such warfare no single general could strike a blow that would make him immortal; the “glory of fighting” sank down into the dirt and mire of trenches and dugouts.

1915

Between the coast and the Vosges was a westward bulge in the trench line, named the Noyon salient after the French town at the maximum point of the German advance near Compiègne. Joffre’s plan for 1915 was to attack the salient on both flanks to cut it off. The Fourth Army had attacked in Champagne from 20 December 1914 – 17 March 1915 but the French were not able to attack in Artois at the same time. The Tenth Army formed the northern attack force and was to attack eastwards into the Douai plain on a 16 km (9.9 mi) front between Loos and Arras. On 10 March, as part of the larger offensive in the Artois region, the British Army fought the Battle of Neuve Chapelle to capture Aubers Ridge. The assault was made by four divisions on a 2 mi (3.2 km) front. Preceded by a hurricane bombardment lasting only 35 minutes, the village was captured within four hours. The advance then slowed because of supply and communication difficulties. The Germans brought up reserves and counterattacked, forestalling the attempt to capture the ridge. Since the British had used about a third of their artillery ammunition, General Sir John French blamed the failure on the Shell Crisis of 1915, despite the early success.

Gas warfare

Main article: Chemical weapons in World War I

All sides had signed the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, which prohibited the use of chemical weapons in warfare. In 1914, there had been small-scale attempts by both the French and Germans to use various tear gases, which were not strictly prohibited by the early treaties but which were also ineffective.The first use of more lethal chemical weapons on the Western Front was against the French near the Belgian town of Ypres. The Germans had already deployed gas against the Russians in the east at the Battle of Humin-Bolimów

Despite the German plans to maintain the stalemate with the French and British, Albrecht, Duke of Württemberg, commander of the 4th Army planned an offensive at Ypres, site of the First Battle of Ypres in November 1914. The Second Battle of Ypres, April 1915, was intended to divert attention from offensives in the Eastern Front and disrupt Franco-British planning. After a two-day bombardment, the Germans released a lethal cloud of 168 long tons (171 t) of chlorine onto the battlefield. Though primarily a powerful irritant, it can asphyxiate in high concentrations or prolonged exposure. Being heavier than air, the gas crept across no man’s land and drifted into the French trenches. The green-yellow cloud started killing some defenders and those in the rear fled in panic, creating an undefended 3.7-mile (6 km) gap in the Allied line. The Germans were unprepared for the level of their success and lacked sufficient reserves to exploit the opening. Canadian troops on the right drew back their left flank and halted the German advance. The gas attack was repeated two days later and caused a 3.1 mi (5 km) withdrawal of the Franco-British line but the opportunity had been lost.

The success of this attack would not be repeated, as the Allies countered by introducing gas masks and other countermeasures. An example of the success of these measures came a year later, on 27 April in the Gas attacks at Hulluch 40 km (25 mi) to the south of Ypres, where the 16th (Irish) Division withstood several German gas attacks. The British retaliated, developing their own chlorine gas and using it at the Battle of Loos in September 1915. Fickle winds and inexperience led to more British casualties from the gas than German. French, British and German forces all escalated the use of gas attacks through the rest of the war, developing the more deadly phosgene gas in 1915, then the infamous mustard gas in 1917, which could linger for days and could kill slowly and painfully. Countermeasures also improved and the stalemate continued.

Air warfare

Main article: Aviation in World War I

Specialised aeroplanes for aerial combat were introduced in 1915. Aircraft were already in use for scouting and on 1 April, the French pilot Roland Garros became the first to shoot down an enemy aircraft by using a machine-gun that shot forward through the propeller blades. This was achieved by crudely reinforcing the blades to deflect bullets. Several weeks later Garros force-landed behind German lines. His aeroplane was captured and sent to Dutch engineer Anthony Fokker, who soon produced a significant improvement, the interrupter gear, in which the machine gun is synchronised with the propeller so it fires in the intervals when the blades of the propeller are out of the line of fire. This advance was quickly ushered into service, in the Fokker E.I (Eindecker, or monoplane, Mark 1), the first single seat fighter aircraft to combine a reasonable maximum speed with an effective armament. Max Immelmann scored the first confirmed kill in an Eindecker on 1 August. Both sides developed improved weapons, engines, airframes and materials, until the end of the war. It also inaugurated the cult of the ace, the most famous being Manfred von Richthofen (the Red Baron). Contrary to the myth, anti-aircraft fire claimed more kills than fighters.

Spring offensive

The final Entente offensive of the spring was the Second Battle of Artois, an offensive to capture Vimy Ridge and advance into the Douai plain. The French Tenth Army attacked on 9 May after a six-day bombardment and advanced 5 kilometres (3 mi) to capture Vimy Ridge. German reinforcements counter-attacked and pushed the French back towards their starting points because French reserves had been held back and the success of the attack had come as a surprise. By 15 May the advance had been stopped, although the fighting continued until 18 June. In May the German Army captured a French document at La Ville-aux-Bois describing a new system of defence. Rather than relying on a heavily fortified front line, the defence was to be arranged in a series of echelons. The front line would be a thinly manned series of outposts, reinforced by a series of strongpoints and a sheltered reserve. If a slope was available, troops were deployed along the rear side for protection. The defence became fully integrated with command of artillery at the divisional level. Members of the German high command viewed this new scheme with some favour and it later became the basis of an elastic defence in depth doctrine against Entente attacks.

During the autumn of 1915, the “Fokker Scourge” began to have an effect on the battlefront as Allied reconnaissance aircraft were nearly driven from the skies. These reconnaissance aircraft were used to direct gunnery and photograph enemy fortifications but now the Allies were nearly blinded by German fighters. However, the impact of German air superiority was diminished by their primarily defensive doctrine in which they tended to remain over their own lines, rather than fighting over Allied held territory.

Autumn offensive

In September 1915 the Entente allies launched another offensive, with the French Third Battle of Artois, Second Battle of Champagne and the British at Loos. The French had spent the summer preparing for this action, with the British assuming control of more of the front to release French troops for the attack. The bombardment, which had been carefully targeted by means of aerial photography began on 22 September. The main French assault was launched on 25 September and, at first, made good progress in spite of surviving wire entanglements and machine gun posts. Rather than retreating, the Germans adopted a new defence-in-depth scheme that consisted of a series of defensive zones and positions with a depth of up to 8.0 km (5 mi).

On 25 September, the British began the Battle of Loos, part of the Third Battle of Artois, which was meant to supplement the larger Champagne attack. The attack was preceded by a four-day artillery bombardment of 250,000 shells and a release of 5,100 cylinders of chlorine gas. The attack involved two corps in the main assault and two corps performing diversionary attacks at Ypres. The British suffered heavy losses, especially due to machine gun fire during the attack and made only limited gains before they ran out of shells. A renewal of the attack on 13 October fared little better. In December, French was replaced by General Douglas Haig as commander of the British forces.

1916

Falkenhayn believed that a breakthrough might no longer be possible and instead focused on forcing a French defeat by inflicting massive casualties. His new goal was to “bleed France white.” As such, he adopted two new strategies. The first was the use of unrestricted submarine warfare to cut off Allied supplies arriving from overseas. The second would be attacks against the French army intended to inflict maximum casualties; Falkenhayn planned to attack a position from which the French could not retreat, for reasons of strategy and national pride and thus trap the French. The town of Verdun was chosen for this because it was an important stronghold, surrounded by a ring of forts, that lay near the German lines and because it guarded the direct route to Paris.

Falkenhayn limited the size of the front to 5–6 kilometres (3–4 mi) to concentrate artillery firepower and to prevent a breakthrough from a counter-offensive. He also kept tight control of the main reserve, feeding in just enough troops to keep the battle going. In preparation for their attack, the Germans had amassed a concentration of aircraft near the fortress. In the opening phase, they swept the air space of French aircraft, which allowed German artillery-observation aircraft and bombers to operate without interference. In May, the French countered by deploying escadrilles de chasse with superior Nieuport fighters and the air over Verdun turned into a battlefield as both sides fought for air superiority.

Battle of Verdun

Main article: Battle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun began on 21 February 1916 after a nine-day delay due to snow and blizzards. After a massive eight-hour artillery bombardment, the Germans did not expect much resistance as they slowly advanced on Verdun and its forts. Sporadic French resistance was encountered. The Germans took Fort Douaumont and then reinforcements halted the German advance by 28 February.

The Germans turned their focus to Le Mort Homme on the west bank of the Meuse which blocked the route to French artillery emplacements, from which the French fired across the river. After some of the most intense fighting of the campaign, the hill was taken by the Germans in late May. After a change in French command at Verdun from the defensive-minded Philippe Pétain to the offensive-minded Robert Nivelle, the French attempted to re-capture Fort Douaumont on 22 May but were easily repulsed. The Germans captured Fort Vaux on 7 June and with the aid of diphosgene gas, came within 1 kilometre (1,100 yd) of the last ridge before Verdun before being contained on 23 June.

Over the summer, the French slowly advanced. With the development of the rolling barrage, the French recaptured Fort Vaux in November and by December 1916 they had pushed the Germans back 2.1 kilometres (1.3 mi) from Fort Douaumont, in the process rotating 42 divisions through the battle. The Battle of Verdun—also known as the ‘Mincing Machine of Verdun’ or ‘Meuse Mill’—became a symbol of French determination and self-sacrifice.

Battle of the Somme

Main article: Battle of the Somme

In the spring, Allied commanders had been concerned about the ability of the French Army to withstand the enormous losses at Verdun. The original plans for an attack around the River Somme were modified to let the British make the main effort. This would serve to relieve pressure on the French, as well as the Russians who had also suffered great losses. On 1 July, after a week of heavy rain, British divisions in Picardy began the Battle of the Somme with the Battle of Albert, supported by five French divisions on their right flank. The attack had been preceded by seven days of heavy artillery bombardment. The experienced French forces were successful in advancing but the British artillery cover had neither blasted away barbed wire, nor destroyed German trenches as effectively as was planned. They suffered the greatest number of casualties (killed, wounded and missing) in a single day in the history of the British Army, about 57,000.

The Verdun lesson learnt, the Allies’ tactical aim became the achievement of air superiority and until September, German aircraft were swept from the skies over the Somme. The success of the Allied air offensive caused a reorganisation of the German air arm and both sides began using large formations of aircraft rather than relying on individual combat. After regrouping, the battle continued throughout July and August, with some success for the British despite the reinforcement of the German lines. By August, General Haig had concluded that a breakthrough was unlikely and instead, switched tactics to a series of small unit actions. The effect was to straighten out the front line, which was thought necessary in preparation for a massive artillery bombardment with a major push.

The final phase of the battle of the Somme saw the first use of the tank on the battlefield. The Allies prepared an attack that would involve 13 British and Imperial divisions and four French corps. The attack made early progress, advancing 3,200–4,100 metres (3,500–4,500 yd) in places but the tanks had little effect due to their lack of numbers and mechanical unreliability. The final phase of the battle took place in October and early November, again producing limited gains with heavy loss of life. All told, the Somme battle had made penetrations of only 8 kilometres (5 mi) and failed to reach the original objectives. The British had suffered about 420,000 casualties and the French around 200,000. It is estimated that the Germans lost 465,000, although this figure is controversial.

The Somme led directly to major new developments in infantry organisation and tactics; despite the terrible losses of 1 July, some divisions had managed to achieve their objectives with minimal casualties. In examining the reasons behind losses and achievements, once the British war economy produced sufficient equipment and weapons, the army made the platoon the basic tactical unit, similar to the French and German armies. At the time of the Somme, British senior commanders insisted that the company (120 men) was the smallest unit of manoeuvre; less than a year later, the section of ten men would be so.

Hindenburg line

Main article: Hindenburg Line

In August 1916 the German leadership along the Western Front had changed as Falkenhayn resigned and was replaced by Hindenburg and Ludendorff. The new leaders soon recognised that the battles of Verdun and the Somme had depleted the offensive capabilities of the German Army. They decided that the German Army in the west would go over to the strategic defensive for most of 1917, while the Central powers would attack elsewhere.

During the Somme battle and through the winter months, the Germans created a fortification behind the Noyon Salient that would be called the Hindenburg Line, using the defensive principles elaborated since the defensive battles of 1915, including the use of Eingreif divisions. This was intended to shorten the German front, freeing 10 divisions for other duties. This line of fortifications ran from Arras south to St Quentin and shortened the front by about 50 kilometres (30 mi). British long-range reconnaissance aircraft first spotted the construction of the Hindenburg Line in November 1916.

1917

Main articles: Hindenburg Line and Western Front tactics, 1917

The Hindenburg Line was built between 2 mi (3.2 km) and 30 mi (48 km) behind the German front line. On 25 February the German armies west of the line began Operation Alberich a withdrawal to the line and completed the retirement on 5 April, leaving a supply desert of scorched earth to be occupied by the Allies. This withdrawal negated the French strategy of attacking both flanks of the Noyon salient, as it no longer existed. The British continued offensive operations as the War Office claimed, with some justification, that this withdrawal resulted from the casualties the Germans received during the Battles of the Somme and Verdun, despite the Allies suffering greater losses.

On 6 April the United States declared war on Germany. In early 1915, following the sinking of the Lusitania, Germany had stopped unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic because of concerns of drawing the United States into the conflict. With the growing discontent of the German public due to the food shortages, the government resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in February 1917. They calculated that a successful submarine and warship siege of Britain would force that country out of the war within six months, while American forces would take a year to become a serious factor on the Western Front. The submarine and surface ships had a long period of success before Britain resorted to the convoy system, bringing a large reduction in shipping losses.

By 1917, the size of the British Army on the Western Front had grown to two-thirds of the size of the French force. In April 1917 the BEF began the Battle of Arras. The Canadian Corps and the 5th Division of the First Army, fought the Battle of Vimy Ridge, completing the capture of the ridge and the Third Army to the south achieved the deepest advance since trench warfare began. Later attacks were confronted by German reinforcements defending the area using the lessons learned on the Somme in 1916. British attacks were contained and, according to Gary Sheffield, a greater rate of daily loss was inflicted on the British than in “any other major battle”.

During the winter of 1916–1917, German air tactics had been improved, a fighter training school was opened at Valenciennes and better aircraft with twin guns were introduced. The result was higher losses of Allied aircraft, particularly for the British, Portuguese, Belgians and Australians who were struggling with outmoded aircraft, poor training and tactics. The Allied air successes over the Somme were not repeated. During their attack at Arras, the British lost 316 air crews and the Canadians lost 114 compared to 44 lost by the Germans. This became known to the Royal Flying Corps as Bloody April.

Nivelle Offensive

Main articles: Battle of Arras (1917), Nivelle Offensive, and 1917 French Army mutinies

The same month, the French Commander-in-chief, General Robert Nivelle, ordered a new offensive against the German trenches, promising that it would end the war within 48 hours. The 16 April attack, dubbed the Nivelle Offensive (also known as the Second Battle of the Aisne), would be 1.2 million men strong, preceded by a week-long artillery bombardment and accompanied by tanks. The offensive proceeded poorly as the French troops, with the help of two Russian brigades, had to negotiate rough, upward-sloping terrain in extremely bad weather. Planning had been dislocated by the voluntary German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line. Secrecy had been compromised and German aircraft gained air superiority, making reconnaissance difficult and in places, the creeping barrage moved too fast for the French troops. Within a week the French suffered 120,000 casualties. Despite the casualties and his promise to halt the offensive if it did not produce a breakthrough, Nivelle ordered the attack to continue into May.

On 3 May the weary French 2nd Colonial Division, veterans of the Battle of Verdun, refused orders, arriving drunk and without their weapons. Lacking the means to punish an entire division, its officers did not immediately implement harsh measures against the mutineers. Mutinies occurred in 54 French divisions and 20,000 men deserted. Other Allied forces attacked but suffered massive casualties. Appeals to patriotism and duty followed, as did mass arrests and trials. The French soldiers returned to defend their trenches but refused to participate in further offensive action. On 15 May Nivelle was removed from command, replaced by Pétain who immediately stopped the offensive. The French would go on the defensive for the following months to avoid high casualties and to restore confidence in the French High Command, while the British assumed greater responsibility.

American Expeditionary Force

On 25 June the first US troops began to arrive in France, forming the American Expeditionary Force. However, the American units did not enter the trenches in divisional strength until October. The incoming troops required training and equipment before they could join in the effort, and for several months American units were relegated to support efforts. Despite this, however, their presence provided a much-needed boost to Allied morale, with the promise of further reinforcements that could tip the manpower balance towards the Allies.

Flanders offensive

Main articles: Battle of Messines (1917) and Third Battle of Ypres

In June, the British launched an offensive in Flanders, in part to take the pressure off the French armies on the Aisne, after the French part of the Nivelle Offensive failed to achieve the strategic victory that had been planned and French troops began to mutiny. The offensive began on 7 June, with a British attack on Messines Ridge, south of Ypres, to retake the ground lost in the First and Second battles in 1914. Since 1915 specialist Royal Engineer tunnelling companies had been digging tunnels under the ridge, and about 500 t (490 long tons) of explosives had been planted in 21 mines under the German defences. Following several weeks of bombardment, the explosives in 19 of these mines were detonated, killing up to 7,000 German troops. The infantry advance that followed relied on three creeping barrages which the British infantry followed to capture the plateau and the east side of the ridge in one day. German counter-attacks were defeated and the southern flank of the Gheluvelt plateau was protected from German observation.

On 11 July 1917, during Unternehmen Strandfest (Operation Beachparty) at Nieuport on the coast, the Germans introduced a new weapon into the war when they fired a powerful blistering agent Sulfur mustard (Yellow Cross) gas. The artillery deployment allowed heavy concentrations of the gas to be used on selected targets. Mustard gas was persistent and could contaminate an area for days, denying it to the British, an additional demoralising factor. The Allies increased production of gas for chemical warfare but took until late 1918 to copy the Germans and begin using mustard gas.

From 31 July to 10 November the Third Battle of Ypres included the First Battle of Passchendaele and culminated in the Second Battle of Passchendaele. The battle had the original aim of capturing the ridges east of Ypres then advancing to Roulers and Thourout to close the main rail line supplying the German garrisons on the Western front north of Ypres. If successful the northern armies were then to capture the German submarine bases on the Belgian coast. It was later restricted to advancing the British Army onto the ridges around Ypres, as the unusually wet weather slowed British progress. The Canadian Corps relieved the II ANZAC Corps and took the village of Passchendaele on 6 November, despite rain, mud and many casualties. The offensive was costly in manpower for both sides for relatively little gain of ground against determined German resistance but the ground captured was of great tactical importance. In the drier periods, the British advance was inexorable and during the unusually wet August and in the Autumn rains that began in early October, the Germans achieved only costly defensive successes, which led the German commanders in early October to begin preparations for a general retreat. Both sides lost a combined total of over a half million men during this offensive.The battle has become a byword among some British revisionist historians for bloody and futile slaughter, whilst the Germans called Passchendaele “the greatest martyrdom of the war.”

Battle of Cambrai

Main article: Battle of Cambrai

On 20 November the British launched the first massed tank attack and the first attack using predicted artillery-fire (aiming artillery without firing the guns to obtain target data) at the Battle of Cambrai. The Allies attacked with 324 tanks (with one-third held in reserve) and twelve divisions, advancing behind a hurricane bombardment, against two German divisions. The machines carried fascines on their fronts to bridge trenches and the 13-foot-wide (4 m) German tank traps. Special “grapnel tanks” towed hooks to pull away the German barbed wire. The attack was a great success for the British, who penetrated further in six hours than at the Third Ypres in four months, at a cost of only 4,000 British casualties. The advance produced an awkward salient and a surprise German counter-offensive began on 30 November, which drove back the British in the south and failed in the north. Despite the reversal, the attack was seen as a success by the Allies, proving that tanks could overcome trench defences. The Germans realised that the use of tanks by the Allies posed a new threat to any defensive strategy they might mount. The battle had also seen the first mass use of German Stosstruppen on the Western front in the attack, who used infantry infiltration tactics to penetrate British defences, bypassing resistance and quickly advancing into the British rear.

1918

Following the successful Allied attack and penetration of the German defences at Cambrai, Ludendorff and Hindenburg determined that the only opportunity for German victory lay in a decisive attack along the Western front during the spring, before American manpower became overwhelming. On 3 March 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed and Russia withdrew from the war. This would now have a dramatic effect on the conflict as 33 divisions were released from the Eastern Front for deployment to the west. The Germans occupied almost as much Russian territory under the provisions of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk as they did in the Second World War but this considerably restricted their troop redeployment. The Germans achieved an advantage of 192 divisions in the west to the 178 Allied divisions, which allowed Germany to pull veteran units from the line and retrain them as Stosstruppen (40 infantry and 3 cavalry divisions were retained for German occupation duties in the east).

The Allies lacked unity of command and suffered from morale and manpower problems, the British and French armies were severely depleted and not in a position to attack in the first half of the year, while the majority of the newly arrived American troops were still training, with just six complete divisions in the line. Ludendorff decided on an offensive strategy beginning with a big attack against the British on the Somme, to separate them from the French and drive them back to the channel ports. The attack would combine the new storm troop tactics with over 700 aircraft, tanks and a carefully planned artillery barrage that would include gas attacks.

German spring offensives

Main article: German spring offensive

Operation Michael, the first of the German spring offensives, very nearly succeeded in driving the Allied armies apart, advancing to within shelling distance of Paris for the first time since 1914.As a result of the battle, the Allies agreed on unity of command. General Ferdinand Foch was appointed commander of all Allied forces in France. The unified Allies were better able to respond to each of the German drives and the offensive turned into a battle of attrition. In May, the American divisions also began to play an increasing role, winning their first victory in the Battle of Cantigny. By summer, between 250,000 and 300,000 American soldiers were arriving every month. A total of 2.1 million American troops would be deployed on this front before the war came to an end. The rapidly increasing American presence served as a counter for the large numbers of redeployed German forces.

Allied counter-offensives

Main articles: Second Battle of the Marne, Hundred Days Offensive, and Armistice of 11 November 1918

In July, Foch began the Second Battle of the Marne, a counter-offensive against the Marne salient which was eliminated by August. The Battle of Amiens began two days later, with Franco-British forces spearheaded by Australian and Canadian troops, along with 600 tanks and 800 aircraft. Hindenburg named 8 August as the “Black Day of the German army.” The Italian 2nd Corps, commanded by General Alberico Albricci, also participated in the operations around Reims. German manpower had been severely depleted after four years of war and its economy and society were under great internal strain. The Allies fielded 216 divisions against 197 German divisions. The Hundred Days Offensive beginning in August proved the final straw and following this string of military defeats, German troops began to surrender in large numbers.As the Allied forces advanced, Prince Maximilian of Baden was appointed as Chancellor of Germany in October to negotiate an armistice. Ludendorff was forced out and fled to Sweden. The German retreat continued and the German Revolution put a new government in power. The Armistice of Compiègne was quickly signed, stopping hostilities on the Western Front on 11 November 1918, later known as Armistice Day. The German Imperial Monarchy collapsed when General Groener, the successor to Ludendorff, backed the moderate Social Democratic Government under Friedrich Ebert, to forestall a revolution like those in Russia the previous year.

Aftermath

Main article: Aftermath of World War I

| Nationality | Killed | Wounded | POW |

|---|---|---|---|

| France | 1,395,000 | c. 6,000,000 | 508,000 |

| United Kingdom | 700,600 | c. 3,000,500 | 223,600 |

| Canada | 56,400 | 259,700 | — |

| United States | 117,000 | 330,100 | 4,430 |

| Australia | 48,900 | 175,900 | — |

| Belgium | 80,200 | 144,700 | 10,200 |

| New Zealand | 12,900 | 34,800 | — |

| India | 6,670 | 15,750 | 1,090 |

| Pakistan | 6,670 | 15,750 | 1,090 |

| Russia | 7,542[f] | 20,000 | — |

| Italy | 4,500[g] | 10,500 | — |

| South Africa | 3,250 | 8,720 | 2,220 |

| Portugal | 1,290 | 13,750 | 6,680 |

| Siam | 19 | — | — |

| Allies | 2,440,941 | c. 10,029,670 | c. 757,310 |

| Germany | 1,593,000 | 5,116,000 | 774,000 |

| Austro-Hungary | 779 | 13,113 | 5,403 |

| Central Powers | 1,593,779 | c. 5,129,113 | c. 779,403 |

| Grand Total | c. 4.034,720 | c. 15,158,783 | c. 1,536,710 |

The war along the Western Front led the German government and its allies to sue for peace in spite of German success elsewhere. As a result, the terms of the peace were dictated by France, Britain and the United States, during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. The result was the Treaty of Versailles, signed in June 1919 by a delegation of the new German government. The terms of the treaty constrained Germany as an economic and military power. The Versailles treaty returned the border provinces of Alsace-Lorraine to France, thus limiting the quantity of coal available to German industry. The Saar, which formed the west bank of the Rhine, would be demilitarized and controlled by Britain and France, while the Kiel Canal opened to international traffic. The treaty also drastically reshaped Eastern Europe. It severely limited the German armed forces by restricting the size of the army to 100,000 and prohibiting a navy or air force. The navy was sailed to Scapa Flow under the terms of surrender but was later scuttled as a reaction to the treaty.

Casualties

Main article: Casualties of World War I

The war in the trenches of the Western Front left tens of thousands of maimed soldiers and war widows. The unprecedented loss of life had a lasting effect on popular attitudes toward war, resulting later in an Allied reluctance to pursue an aggressive policy toward Adolf Hitler. Belgium suffered 30,000 civilian dead and France 40,000 (including 3,000 merchant sailors). The British lost 16,829 civilian dead; 1,260 civilians were killed in air and naval attacks, 908 civilians were killed at sea and there were 14,661 merchant marine deaths. Another 62,000 Belgian, 107,000 British and 300,000 French civilians died due to war-related causes.

Economic costs

See also: French war planning 1920–1940

Germany in 1919 was bankrupt, the people living in a state of semi-starvation and having no commerce with the remainder of the world. The Allies occupied the Rhine cities of Cologne, Koblenz and Mainz, with restoration dependent on payment of reparations. In Germany a Stab-in-the-back myth (Dolchstoßlegende) was propagated by Hindenburg, Ludendorff and other defeated generals, that the defeat was not the fault of the ‘good core’ of the army but due to certain left-wing groups within Germany who signed a disastrous armistice; this would later be exploited by nationalists and the Nazi party propaganda to excuse the overthrow of the Weimar Republic in 1930 and the imposition of the Nazi dictatorship after March 1933.

France suffered more casualties relative to its population than any other great power and the industrial north-east of the country was devastated by the war. The provinces overrun by Germany had produced 40 percent of French coal and 58 percent of its steel output. Once it was clear that Germany was going to be defeated, Ludendorff had ordered the destruction of the mines in France and Belgium. His goal was to cripple the industries of Germany’s main European rival. To prevent similar German attacks in the future, France later built a massive series of fortifications along the German border known as the Maginot Line.