i’m going to Kirby Lonsdale next week. I am looking forward to this.

Weevles Updates Disabled Bloggers Team

Weevl Bloggers Corner

For all blog posts without a category

i’m going to Kirby Lonsdale next week. I am looking forward to this.

The British government mobilised civilians more effectively than any other combatant nation. By 1944 a third of the civilian population were engaged in war work, including over 7,000,000 women.

Minister of Labour Ernest Bevin was responsible for Britain’s manpower resources. He introduced the Essential Work Order (EWO) which became law in March 1941. The EWO tied workers to jobs considered essential for the war effort and prevented employers from sacking workers without permission from the Ministry of Labour.

Bevin was also responsible for overhauling the reserved occupations scheme that gave groups of skilled workers in certain occupations exemption from military service.

Art

Image: IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 2850)

Ruby Loftus had been brought to the attention of the War Artist’s Advisory Committee as ‘an outstanding factory worker’.

Artist Laura Knight had originally expected to produce a studio portrait of Miss Loftus, however, the Ministry of Supply requested that she be painted at work in the Royal Ordnance Factory in Newport, South Wales.

Here we see 21-year-old Ruby Loftus making a Bofors Breech ring, a task considered to be the most highly skilled job in the factory, normally requiring eight or nine years training.

Ernest Bevin met with Ruby Loftus during a visit to No 11 Royal Ordnance Factory in 1943.

Image: IWM (HU 36287)

Women working in a Royal Ordnance Factory prepare for their shift in the “beauty parlour”.

From early 1941, it became compulsory for women aged between 18 and 60 to register for war work. Conscription of women began in December.

Unmarried ‘mobile’ women between the ages of 20 and 30 were called up and given a choice between joining the services or working in industry.

Pregnant women, those who had a child under the age of 14 or women with heavy domestic responsibilities could not be made to do war work, but they could volunteer. ‘Immobile’ women, who had a husband at home or were married to a serviceman, were directed into local war work.

As well as men and women carrying out paid war work in Britain’s factories, there were also thousands of part-time volunteer workers contributing to the war effort on top of their every day domestic responsibilities.

Other vital war work was carried out on the land and on Britain’s transport network.

During the spring of 1939 the deteriorating international situation forced the British government under Neville Chamberlain to consider preparations for a possible war against Nazi Germany.

Plans for limited conscription applying to single men aged between 20 and 22 were given parliamentary approval in the Military Training Act in May 1939. This required men to undertake six months’ military training, and some 240,000 registered for service.

On the day Britain declared war on Germany, 3 September 1939, Parliament immediately passed a more wide-reaching measure.

The National Service (Armed Forces) Act imposed conscription on all males aged between 18 and 41 who had to register for service. Those medically unfit were exempted, as were others in key industries and jobs such as baking, farming, medicine, and engineering.

Conscientious objectors had to appear before a tribunal to argue their reasons for refusing to join-up. If their cases were not dismissed, they were granted one of several categories of exemption, and were given non-combatant jobs.

Conscription helped greatly to increase the number of men in active service during the first year of the war.

In December 1941 Parliament passed a second National Service Act. It widened the scope of conscription still further by making all unmarried women and all childless widows between the ages of 20 and 30 liable to call-up.

Men were now required to do some form of National Service up to the age of 60, which included military service for those under 51. The main reason was that there were not enough men volunteering for police and civilian defence work, or women for the auxiliary units of the armed forces.

William Francis Eve (1894-1981) was born in Clapham, London, on 22 September 1894, the son of Richard Edward Eve and Emmeline Augusta Eve. His father was a silversmith and the family lived at 9 Solon New Road, Clapham.

By 1911 William had moved in with his uncle Henry James Melhius and his wife Blanche Millicent at 3 Highworth Gardens, Midhurst Road, West Ealing, Middlesex. Around this time he also joined the Territorial Force, enlisting with The Queen’s Westminster Rifles.

Following the outbreak of war, Eve was called up on 26 August 1914 and joined his unit at its headquarters at 58 Buckingham Gate. Like most Territorial soldiers he immediately volunteered for ‘Foreign Service’.

After forming up at Hemel Hempstead, his battalion eventually landed at Le Havre on 2 November. The Queen’s Westminster Rifles were amongst the very first Territorials to enter the line as reinforcements for the hard-pressed British Expeditionary Force (BEF).

On recovering from trench foot, Eve was promoted to lance-corporal and eventually commissioned in September 1915 as a second lieutenant in the 2/6th (City of London) Battalion (Rifles), The London Regiment. Unfortunately, he developed epilepsy and was invalided from the Army in July 1916.

Eve settled at 79 Harrow View, Harrow, Middlesex. He married in 1922 and lived in Surrey where he died in February 1981.

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leading the United Kingdom during the First World War, for social-reform policies, for his role in the Paris Peace Conference, and for negotiating the establishment of the Irish Free State.

Born in Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, and raised in Llanystumdwy, Lloyd George gained a reputation as an orator and proponent of a Welsh blend of radical Liberal ideas that included support for Welsh devolution, the disestablishment of the Church of England in Wales, equality for labourers and tenant farmers, and reform of land ownership. He won an 1890 by-election to become the Member of Parliament for Caernarvon Boroughs, and was continuously re-elected to the role for 55 years. He served in Henry Campbell-Bannerman‘s cabinet from 1905. After H. H. Asquith succeeded to the premiership in 1908, Lloyd George replaced him as Chancellor of the Exchequer. To fund extensive welfare reforms, he proposed taxes on land ownership and high incomes in the 1909 People’s Budget, which the Conservative-dominated House of Lords rejected. The resulting constitutional crisis was only resolved after elections in 1910 and passage of the Parliament Act 1911. His budget was enacted in 1910, with the National Insurance Act 1911 and other measures helping to establish the modern welfare state. He was embroiled in the 1913 Marconi scandal but remained in office and secured the disestablishment of the Church of England in Wales.

In 1915, Lloyd George became Minister of Munitions and expanded artillery shell production for the war. In 1916, he was appointed Secretary of State for War but was frustrated by his limited power and clashes with Army commanders over strategy. Asquith proved ineffective as prime minister and was replaced by Lloyd George in December 1916. He centralised authority by creating a smaller war cabinet. To combat food shortages caused by u-boats, he implemented the convoy system, established rationing, and stimulated farming. After supporting the disastrous French Nivelle Offensive in 1917, he had to reluctantly approve Field Marshal Douglas Haig‘s plans for the Battle of Passchendaele, which resulted in huge casualties with little strategic benefit. Against British military commanders, he was finally able to see the Allies brought under one command in March 1918. The war effort turned in the Allies’ favour and was won in November. Following the December 1918 “Coupon” election, he and the Conservatives maintained their coalition with popular support.

Lloyd George was a leading proponent at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, but the situation in Ireland worsened, erupting into the Irish War of Independence, which lasted until Lloyd George negotiated independence for the Irish Free State in 1921. At home, he initiated education and housing reforms, but trade-union militancy rose to record levels, the economy became depressed in 1920 and unemployment rose; spending cuts followed in 1921–22, and in 1922 he became embroiled in a scandal over the sale of honours and the Chanak Crisis. The Carlton Club meeting decided the Conservatives should end the coalition and contest the next election alone. Lloyd George resigned as prime minister, but continued as the leader of a Liberal faction. After an awkward reunion with Asquith’s faction in 1923, Lloyd George led the weak Liberal Party from 1926 to 1931. He proposed innovative schemes for public works and other reforms, but made only modest gains in the 1929 election. After 1931, he was a mistrusted figure heading a small rump of breakaway Liberals opposed to the National Government. In 1940, he refused to serve in Churchill’s War Cabinet. He was elevated to the peerage in 1945 but died before he could take his seat in the House of Lords.

David George was born on 17 January 1863 in Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, to Welsh parents William George and Elizabeth Lloyd George. William died in June 1864 of pneumonia, aged 44. David was just over one year old. Elizabeth George moved with her children to her native Llanystumdwy in Caernarfonshire, where she lived in a cottage known as Highgate with her brother Richard, a shoemaker, lay minister and a strong Liberal. Richard Lloyd was a towering influence on his nephew and David adopted his uncle’s surname to become “Lloyd George”. Lloyd George was educated at the local Anglican school, Llanystumdwy National School, and later under tutors.

He was brought up with Welsh as his first language; Roy Jenkins, another Welsh politician, notes that, “Lloyd George was Welsh, that his whole culture, his whole outlook, his language was Welsh.”

Though brought up a devout evangelical, Lloyd George privately lost his religious faith as a young man. Biographer Don Cregier says he became “a Deist and perhaps an agnostic, though he remained a chapel-goer and connoisseur of good preaching all his life.” He was nevertheless, according to Frank Owen, “one of the foremost fighting leaders of a fanatical Welsh Nonconformity” for a quarter of a century.

Lloyd George qualified as a solicitor in 1884 after being articled to a firm in Porthmadog and taking Honours in his final law examination. He set up his own practice in the back parlour of his uncle’s house in 1885. Although many prime ministers have been barristers, Lloyd George is, as of 2025, the only solicitor to have held that office.

As a solicitor, Lloyd George was politically active from the start, campaigning for his uncle’s Liberal Party in the 1885 election. He was attracted by Joseph Chamberlain‘s “unauthorised programme” of Radical reform. After the election, Chamberlain split with William Ewart Gladstone in opposition to Irish Home Rule, and Lloyd George moved to join the Liberal Unionists. Uncertain of which wing to follow, he moved a resolution in support of Chamberlain at a local Liberal club and travelled to Birmingham to attend the first meeting of Chamberlain’s new National Radical Union, but arrived a week too early. In 1907 Lloyd George would tell Herbert Lewis that he had thought Chamberlain’s plan for a federal solution to the Home Rule Question correct in 1886 and still thought so, and that “If Henry Richmond, Osborne Morgan and the Welsh members had stood by Chamberlain on an agreement as regards the [Welsh] disestablishment, they would have carried Wales with them”

His legal practice quickly flourished; he established branch offices in surrounding towns and took his brother William into partnership in 1887.Lloyd George’s legal and political triumph came in the Llanfrothen burial case, which established the right of Nonconformists to be buried according to denominational rites in parish burial grounds, as given by the Burial Laws Amendment Act 1880 but theretofore ignored by the Anglican clergy. On Lloyd George’s advice, a Baptist burial party broke open a gate to a cemetery that had been locked against them by the vicar. The vicar sued them for trespass and although the jury returned a verdict for the party, the local judge misrecorded the jury’s verdict and found in the vicar’s favour. Suspecting bias, Lloyd George’s clients won on appeal to the Divisional Court of Queen’s Bench in London, where Lord Chief Justice Coleridge found in their favour. The case was hailed as a great victory throughout Wales and led to Lloyd George’s adoption as the Liberal candidate for Carnarvon Boroughs on 27 December 1888. The same year, he and other young Welsh Liberals founded a monthly paper, Udgorn Rhyddid (Bugle of Freedom).

In 1889, Lloyd George became an alderman on Carnarvonshire County Council (a new body which had been created by the Local Government Act 1888) and would remain so for the rest of his life.Lloyd George would also serve the county as a Justice of the Peace (1910), chairman of Quarter Sessions (1929–38), and Deputy Lieutenant in 1921.

Lloyd George married Margaret Owen, the daughter of a well-to-do local farming family, on 24 January 1888. They had five children.

Lloyd George’s career as a member of parliament began when he was returned as a Liberal MP for Caernarfon Boroughs (now Caernarfon), narrowly winning the by-election on 10 April 1890, following the death of the Conservative member Edmund Swetenham. He would remain an MP for the same constituency until 1945, 55 years later. Lloyd George’s early beginnings in Westminster may have proven difficult for him as a radical liberal and “a great outsider”.[10] Backbench members of the House of Commons were not paid at that time, so Lloyd George supported himself and his growing family by continuing to practise as a solicitor. He opened an office in London under the name of “Lloyd George and Co.” and continued in partnership with William George in Criccieth. In 1897, he merged his growing London practice with that of Arthur Rhys Roberts (who was to become Official Solicitor) under the name of “Lloyd George, Roberts and Co.”

Kenneth O. Morgan describes Lloyd George as a “lifelong Welsh nationalist” and suggests that between 1880 and 1914 he was “the symbol and tribune of the national reawakening of Wales“, although he is also clear that from the early 1900s his main focus gradually shifted to UK-wide issues. He also became an associate of Tom Ellis, MP for Merioneth, having previously told a Caernarfon friend in 1888 that he was a “Welsh Nationalist of the Ellis type”.

One of Lloyd George’s first acts as an MP was to organise an informal grouping of Welsh Liberal members with a programme that included; disestablishing and disendowing the Church of England in Wales, temperance reform, and establishing Welsh home rule. He was keen on decentralisation and thus Welsh devolution, starting with the devolution of the Church in Wales saying in 1890: “I am deeply impressed with the fact that Wales has wants and inspirations of her own which have too long been ignored, but which must no longer be neglected. First and foremost amongst these stands the cause of Religious Liberty and Equality in Wales. If returned to Parliament by you, it shall be my earnest endeavour to labour for the triumph of this great cause. I believe in a liberal extension of the principle of Decentralization.”

During the next decade, Lloyd George campaigned in Parliament largely on Welsh issues, in particular for disestablishment and disendowment of the Church of England. When Gladstone retired in 1894 after the defeat of the second Home Rule Bill, the Welsh Liberal members chose him to serve on a deputation to William Harcourt to press for specific assurances on Welsh issues. When those assurances were not provided, they resolved to take independent action if the government did not bring a bill for disestablishment. When a bill was not forthcoming, he and three other Welsh Liberals (D. A. Thomas, Herbert Lewis and Frank Edwards) refused the whip on 14 April 1894, but accepted Lord Rosebery‘s assurance and rejoined the official Liberals on 29 May.

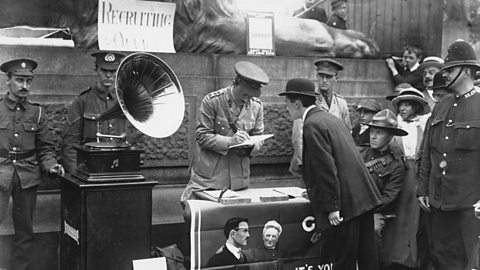

In August 1914, Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, realised Britain needed a bigger army.

He made a direct appeal to the men of Britain. Posters showed him pointing his finger at anyone passing by.

Men felt proud to fight for their country.

In the first weekend of the war, 100 men an hour (3,000 a day) signed up to join the armed forces.

By the end of 1914 1,186,337 men had enlisted.

Image gallerySkip image gallery

1. Photograph of a man giving his name to an officer at a recruitment drive in Trafalgar Square during World War One, 3.Recruitment drives were held in places like Trafalgar Square Only men aged between 18 and 41 could become soldiers. (The age limit was increased to 51 in April 1918.)

The Government wanted as many men as possible to join the forces willingly.

But in 1916 a law was passed to say men had to join whether they wanted to or not. This was called conscription.

“I’m looking forward to watching my YouTube preview tonight at 19:00. It’s a preview of the new route I’m following: Exeter – Plymouth – Paignton.”

During World War I, Britain primarily sourced its food through imports from its empire and other countries like the USA and Canada, as it only produced 40% of its food domestically. When German U-boats threatened these supply lines, Britain implemented a strict rationing system and a national propaganda campaign to increase domestic agricultural production, urging farmers to plow up more grassland and grow more cereals to feed the nation.

Dependence on Imports

The German Threat

Government and Public Response

Alfred was a Trinidadian and Tobagonian of Portuguese descent who served with the British Army during the First World War.

He fought for two years in Flanders and was awarded the Military Medal for bravely putting his own safety at risk to locate and rescue injured soldiers across No Man’s Land at the Battle of Passchendaele in mid-1917.

Due to his short stature, Alfred Mendes was often used as a messenger, having to brave No Man’s Land’s horrors and hazards.

Alfred recorded one incident in his autobiography.

On the morning of October 12, 1917, Alfred’s company received orders to “go forward to meet him with fixed bayonets”, if the German Army were encountered.

Alfred’s C Company had lost contact with A, B and D Companies. Alfred, highly aware of the dangers sending a lone messenger into No Man’s Land brings, immediately volunteered to find the missing companies.

“The snipers got wind of me, and their individual bullets were soon seeking me out,” wrote Alfred, “until I came to the comforting conclusion that they were so nonplussed at seeing a lone man wandering circles about No Man’s Land, as must at times have been the case, that they decided, out of perhaps a secret admiration for my nonchalance, to dispatch their bullets safely out of my way.”

Alfred managed to find the wayward units and spent two days carrying messages between the companies. He returned “without a scratch but certainly with a series of hair-raising experiences that would keep my grand-and great-grandchildren enthralled for nights on end.”

In an interview with Variety, Sam Mendes said he had a childhood memory of Albert sharing a story about a “messenger who has a message to carry through”.

“It lodged with me as a child, this story or this fragment, and obviously I’ve enlarged it and changed it significantly,” Mendes said.

Ultimately, the story Sam Mendes told in 1917 of the pair of Lance-Corporals is fictional, insofar as there was no specific mission undertaken by Blake and Schofield to halt an attack on German lines on 6th April 1917.

However, the look and feel of the film 1917 is such, coupled with the urgency of the cinematography and performances, that it feels sufficiently authentic, as much as the popular image of World War One is often depicted.

But what about 1917’s historical accuracy? The movie strives for authenticity in the action and imagery it offers, but are the events depicted in line with the British or Commonwealth soldier’s experiences on the Western Front?

Image: British soldiers go over the top on the Western Front (© IWM Q 7009)

Sam Mendes employed historical and technical advisors Andrew Robertshaw and Paul Biddiss to work on the film. Their knowledge helped ground the actors in the physical and historical context of that specific period.

One of the key plot points is the sudden German withdrawal from the section of the line near Ecoust, northern France. The British Army had been caught unawares and the retreating Germans had left a blighted, scored land, stripped of resources and infrastructure, for the British to navigate.

This has a strong basis in reality. On 5th April 1917, the Imperial German Army completed Operation Alberich: a strategic retreat aimed at shortening the German line and strengthening new positions across the newly built Hindenburg Line.

The devastation wrought during Alberich was huge. Anything the Allies could use (pipes, cables, roads, bridges, tunnels, and even entire villages) was smashed to pieces.

Image: A mine crater in Athies, Pas-de-Calais, blasted to impede any British advance following Operation Alberich (Wikimedia Commons)

1917 also depicts many black and Sikh soldiers on the frontline to show this “wasn’t a war fought just by white men”.

Image: A Great War-era Sikh soldier. While Sikhs fought in great numbers on European battlefields, by the time of the film 1917’s events, they had been moved to other theatres (© IWM Q 24754)

The First World War was truly a global conflict, bringing in people and cultures from across the world to fight. Mendes is entirely right to point out this wasn’t simply a white man’s war, but the manner in which soldiers are presented is inaccurate.

Tens of thousands of black soldiers served with the British Army and many hundreds of thousands of black Africans served as part of the labour corps during the war. For instance, the British West Indian Regiment sent 15,000 men from the Caribbean to Europe to serve but their roles were restricted to support and logistical duties.

Likewise, Sikh and Indian personnel fought across the battlefields of the Great War. More than 74,000 Indian personnel of World War One are in Commonwealth War Graves’ care.

In the case of the movie 1917, however, the Sikh regiments had long since transferred away from the Western Front. After fighting in the brutal campaigns of 1915 at Neuve Chapelle, Ypres, and the Somme, the Sikhs had taken major casualties and transferred to other theatres of conflict.

At the time of 1917’s fictional story, no Sikh soldiers would have been in France or Belgium, and it would be unlikely to see a single Sikh soldier mixing in with British units as shown in the movie 1917.

Another inaccuracy is the care of wounded troops.

In 1917, as casualties mount, wounded men are taken to a casualty clearing station, just metres from the frontline. Medical tents spread out over an open field as surgeons do their level best to aid their injured comrades.

Image: A Great War Casualty Clearing Station. Such stations would be far from the frontline, unlike the facility shown in 1917 (© IWM CO 3151)

The reality of getting wounded treatment was significantly more complex. Sometimes, depending on the nature of the battlefield, aid posts could be on the frontlines.

It is very unlikely, however, that they would set up a major medical hub so close to the front with little to no cover as depicted in 1917.

These places were hugely important but vulnerable, so would be built in abandoned buildings, underground bunkers, and even shell craters. Keeping them out in the open would present unnecessary danger.

Returning to 1917’s historical accuracies, it’s worth highlighting the touching interaction between Schofield and a French civilian nursing a baby amid the rubble of a shattered Ecoust. While this scenario is fictional it has its roots in reality.

One of the objectives of Operation Alberich was to ensure as many French and Belgian refugees stayed in the Allied sector as possible.

Why? Extra mouths to feed. More civilians in Allied care meant more resources diverted to feed, clothe, and house them. In a conflict such as the First World War, any way to disadvantage your opponent must be explored.

The devastation wrought on Ecoust is accurate too. Towns and villages across Northern France and Flanders were obliterated wholesale. Look at Ypres for example.

Image: Two soldiers stand amidst the devastation of Ypres town centre. Towns and villages across France and Flanders suffered a similar fate during the Great War, something 1917 accurately depicts (© IWM Q 56727)

The city was reduced to rubble and had to be built from the ground up post-war.

Overall, 1917 veers towards historical accuracy but many liberties have been taken to tell the story Sam Mendes wanted to tell. This is often the case.

Take for instance the film’s final British charge.

Once the whistle blows, the British infantry stream over the top in a solid mass with little attempt at unit cohesion. There’s no artillery support either, indicating this attack really would have been suicidal if Schofield hadn’t completed his mission.

In reality, all along the front Officers and Non-Commission Officers would be amongst their men, keeping them together, and guiding the attack. World War One infantry assaults were not simply picking up a gun and running at the enemy as presented in 1917’s climax.

Trenches are probably the first thing people think of when they think of the Western Front.

Image: A section of flooded British trench (© IWM E(AUS) 575)

Image: A section of flooded British trench (© IWM E(AUS) 575)

Hundreds of miles of trenches were dug across the war, stretching from Calais in Northern France to the Swiss border (although not in one continuous, unbroken line).

1917 presents trenches in different states.

We start with a British reserve trench in good condition, topped with sandbags and well-ordered dugouts. Troops mill to and forth on their way to their reserve areas or to move onto the frontline.

Elsewhere, we get a glimpse of British frontline trenches, replete with shell damage, puddles of mud, hungry opportunistic rats, and exhausted soldiers sheltering and snatching sleep while they can.

We see abandoned German trenches too: deeper, sturdier with large-scale bunkhouses, kitchens, and storage sections.

As a war film, 1917 presents an accurate portrayal of trench life. The rear communication and transport trenches are in better condition than the more robust, damaged frontline trenches.

One thing you may notice about the frontline troops is the boredom. 1917’s crew charged the extras with taking on soldiers’ daily routines to add to the sense of monotony many at the front experienced.

Fighting was only a small part of trench life. 1917 shows this by showing soldiers inspecting their clothes for lice, cleaning their boots, scooping mud, and water out of the trench, playing games like chess or cards, reading novels, or simply trying to sleep.

1917 was a tumultuous year for the Allies.

February saw the German Navy recommence unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic. Any ship crossing the ocean was fair game for German submariners. Over a million tons of Allied shipping was lost in February 1917 alone.

On the real April 6, 1917, the date on which the film’s fictional events take place, the United States declared war on Imperial Germany. This would have major consequences for Germany, as it was now facing the prospect of millions of fresh, well-equipped troops being sent to the Western Front.

Major offensives that took place in 1917 include the Battle of Arras in April 1917, which included the stunning Canadian victory at Vimy, but the year is mostly dominated by Passchendaele.

The Third Battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele, took place between July and November in the Ypres Salient in Belgium, Ypres.

Passchendaele is one of the defining battles of the First World War. It drew in millions of men on both sides, resulting in hundreds of thousands of casualties and deaths. Soldiers attacked through the churning bogs of No Man’s Land to be cut down by determined defenders.

Ultimately, the British Army advanced five miles and captured the important high ground around Ypres. Casualties were still shockingly high for such a comparatively small gain.

1917, the war film, really takes place in the opening stages that would go on to be a pivotal year in the course of the First World War.

While the trials and tribulations of Lance-Corporal Blake and Schofield across 1917 are fictional, they draw heavily on the reality of the war. And for many, the Great War’s reality was also tinged with finality.

At the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, we are charged with caring for the Commonwealth’s war dead in perpetuity.

An interesting production quirk of the 1917 film was all the extras playing British soldiers were given a real-life soldier to inhabit. Many of these men would not survive the war.

Commonwealth casualties of the First World War are instead commemorated in our war cemeteries.

For instance, 1917 showcases the Devonshires charging into battle, with troops cut down by machine-gun bullets or artillery blasts.

But did you know the Devonshires have their own small war cemetery maintained by Commonwealth War Graves?

Image: Devonshire Cemetery, Mametz

Devonshire Cemetery, Mametz, marks the spot of the 8th and 9th Battalions of the Devonshire Regiment’s positions on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. 153 Devonshires are buried in the cemetery to this day.

If a casualty fell during the World War One but has no known war grave, they would be commemorated on a WW1 memorial, such as the Menin Gate or Thiepval Memorial.

1917 may have been fiction but our mission is very real.

Do you have a Blake or a Schofield in your family? If they fell in the First World War, they are commemorated by us, and we can help you uncover their story.

Use our Find War Dead tool to uncover their stories. Search by name, rank, country commemorated in, and many more fields designed to make your casualty search as smooth as possible.

James Burns was born in Newcastle in 1897. He had 8 brothers and sisters and his eldest sister Mary who was 18 years old took care of the family as their parents had died very young. There was not alot of money as their was no welfare state then. They did have aunts and uncles who helped them.

James lied about his age to join the Army and said he was born in 1896 which made him 18 but he was actually only 16 because his birthday was not till the September. So when world war one came in August 1914 he could join up to the Army and not be a burden to his family. He would have somewhere to lay his head and be fed three times a day.

They were dark days and he was given the role of a gunner in the Northumbria Fuseliers. The big guns which were pulled by horses. So the gunners had to look after the horses as well feed them take care of them and get them water to drink.

The men had to created latrines for the men each time they decided their base for operations. Set up a food station and a medical tent. Alot of soldiers worked in wet mud most of the time and suffered from trench foot. Fleas had to be burned out the the seams in their uniform which came from the rats looking for food which lived in the trenches with them. A candle was run up the seams to kill the fleas but it was just as bad the nest day.

Many a time the food run out because of war supplies were often cut off from the front line. The red cross used to give the men tins of corned beef to survive on and many said they would have starved if the Red Cross had not been so brave and kind.

Dysentry was also a problem because of the filth not being able to wash your hand before eating or after going to the toilet. Germs passed from one person to another.

James was wounded and had a metal plate in his head after an explosion and was also gassed in the trenches. The guns were targetted by the Germans who tried to blow them up with mortar shells and bombs.

James met Agnes Elizabeth Todd born in August 1901 in Newcastle where she was in service to a Lord and Lady when he was 25 years old and she was 21 years old. They married in 1922 and had three children two girls and a boy. James first in 1925, Mary in 1927 and Agnes in 1928.

James died in 1953 of stomach cancer form the gassing but he did get to hold his grand daughter before he died. The only grandchild born from Mary his daughter. His son James died aged 47 years in 1975 after suffering for many years from Epilepsy endured in a fall as a trainee plumber by falling off a roof. He married but had no children.

Agnes died aged 60 years in 1989 from complications of medication for Rhematoid Arthritis which she developed in her 20’s. She married but had no children.

James wife Agnes died in 1988 aged 87 years of heart problems after a life of hard work and looking after a wounded husband.

Mary their daughter lived to a great age of 97 years she too worked hard as a tailoress and was widowed at 35 years. Her husband was a carpenter and was working away from home and died in a car crash.

Nothing is known of the 8 brothers and sisters James Burns had and nothing is known why his parents died so young, but the spanish influenza took many in the early days of the century. Many children did not live passed the age of 5 years as chicken pox, measles, whooping cough, influenza, was rife with no immunisations available in those days.