Thank you to Caroline Powell for Designing these marketing posters.

Local scene called Seaton Sluice

Tynemouth Priory

St Mary’s Lighthouse

Spanish City

Weevles Updates Disabled Bloggers Team

Weevl Bloggers Corner

For all blog posts without a category

Thank you to Caroline Powell for Designing these marketing posters.

Local scene called Seaton Sluice

Tynemouth Priory

St Mary’s Lighthouse

Spanish City

During World War I, Newcastle upon Tyne was a global hub for armament production, primarily through the industrial giant Armstrong Whitworth. The company’s massive Elswick and Scotswood works produced a vast array of war materiel, making it the largest munitions company in the world at the time.

Key Armaments and Production

The factories along the River Tyne manufactured a wide variety of armaments and related equipment:

The Industrial Landscape

The vast scale of the Newcastle armaments industry meant the region had a disproportionately large impact on the war effort and its eventual outcome.

Gary is eating my sweets. Naughty boy!

In the Nuremberg Trials, the Allies indicted and prosecuted leaders of Nazi Germany after World War II ended. The trials lasted from November 1945 to October 1946 and took place in Nuremberg, Germany.

In total, 199 defendants were tried at Nuremberg; 161 were found guilty, and 37 were sentenced to death. Each trial had a combination of judges from the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and France.

First, the Allies charged 24 top Nazi leaders for their crimes. The judges found most of them guilty of war crimes, starting wars of aggression, crimes against humanity, and conspiracy. Evidence about the Holocaust played a major role in the trial. The judges called the Holocaust one of the worst crimes in history.

After the first trial, the Allies held 12 additional trials. These included separate trials for Nazi physicians, members of the Einsatzgruppen, and German judges.

The Nuremberg Trials weren’t just about punishment. They were also about showing the world what happened during the war and making sure people understood how serious these crimes were.

These trials were important because they created new rules to prevent such crimes in the future. They also showed that even powerful leaders would face justice if they broke international laws.

The International Military Tribunal was opened on October 18, 1945, in the Supreme Court Building in Berlin.

Judge Nikitchenko from the Soviet Union presided over the first session. The prosecution brought criminal charges against 24 Nazi leaders. The indictments were for:

The 24 accused were:

“I” indicted “G” indicted and found guilty “O” Not Charged

| Name | Count | Sentence | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

Martin Bormann | I | O | G | G | Death | Successor to Hess as Nazi Party Secretary. Sentenced to death while not being at the courtroom. His body was found in 1972.[5] |

Karl Dönitz | I | G | G | O | 10 years | Leader of the Kriegsmarine (the Navy) from 1943. Started the U-boat campaign. Became President of Germany after Hitler’s death.[6] In evidence presented at the trial of Karl Dönitz on his orders to the U-boat fleet to breach the London Rules, Admiral Chester Nimitz stated that unrestricted submarine warfare was carried on in the Pacific Ocean by the United States from the first day that nation entered the war. Dönitz was found guilty of breaching the 1936 Second London Naval Treaty, but his sentence was not assessed on the ground of his breaches of the international law of submarine warfare.[7] |

Hans Frank | I | O | G | G | Death | Reich Law Leader 1933–1945 and Governor-General of the General Government in occupied Poland 1939–1945. Expressed sorrow.[8] |

Wilhelm Frick | I | G | G | G | Death | Hitler’s Minister of the Interior (1933–1943) and Reich Protector of Bohemia–Moravia (1943–1945). One of the writers of the Nuremberg Laws.[9] |

Hans Fritzsche | I | I | I | O | Acquitted | Popular radio commentator and head of the news division of the Nazi Propaganda Ministry. Tried in place of Joseph Goebbels.[10] |

Walther Funk | I | G | G | G | Life Imprisonment | Hitler’s Minister of Economics. Succeeded Schacht as head of the Reichsbank. Released from prison due to ill health on May 16, 1957.[11] |

Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring | G | G | G | G | Death | Commander of the Luftwaffe (1935–1945), Chief of the 4-Year Plan (1936–1945), leader of several departments of the SS, and Prime Minister of Prussia. Committed suicide the night before his execution.[12] |

| Rudolf Hess | G | G | I | I | Life Imprisonment | Hitler’s deputy, flew to Scotland in 1941 to try to make peace with Great Britain. After trial he was sent to Spandau Prison and died there in 1987.[13] |

Generaloberst Alfred Jodl | G | G | G | G | Death | Wehrmacht. Keitel’s deputy and Chief of the OKW‘s Operations Division (1938–1945). Later exonerated by a German court in 1953.[14] |

Ernst Kaltenbrunner | I | O | G | G | Death | Highest surviving SS leader. Chief of RSHA 1943–45, the central Nazi intelligence office. Commanded many of the Einsatzgruppen and several concentration camps.[15] |

Wilhelm Keitel | G | G | G | G | Death | Head of Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) 1938–1945.[16] |

| Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach | I | I | I | —- | Major Nazi industrialist. CEO of Krupp AG 1912–45. Medically unfit for trial. The prosecutors attempted to substitute his son Alfried (who ran Krupp for his father during most of the war) in the indictment, but the judges ruled it was too close to trial. Alfried was tried in a separate Nuremberg trial for his use of slave labor, thus escaping the worst notoriety and possibly death. | |

Robert Ley | I | I | I | I | —- | Head of DAF, The German Labour Front. Killed himself on October 25, 1945, before the trial began. |

Konstantin Freiherr von Neurath | G | G | G | G | 15 years | Minister of Foreign Affairs 1932–1938, succeeded by von Ribbentrop. Protector of Bohemia and Moravia 1939–43. Resigned in 1943 after a dispute with Hitler. Released from prison because of ill health on November 6, 1954.[17] |

Franz von Papen | I | I | O | O | Acquitted | Chancellor of Germany in 1932 and Vice-Chancellor under Hitler in 1933–1934. Ambassador to Austria 1934–38 and ambassador to Turkey 1939–1944. Although acquitted at Nuremberg, von Papen was classed as a war criminal in 1947 by a German de-Nazification court, and sentenced to eight years’ hard labour. He was acquitted following appeal after serving two years.[18] |

| Erich Raeder | G | G | G | O | Life Imprisonment | Commander-in-Chief of the Kriegsmarine from 1928 until his retirement in 1943, succeeded by Dönitz. Released because of ill health on September 26, 1955.[19] |

Joachim von Ribbentrop | G | G | G | G | Death | Ambassador-Plenipotentiary 1935–1936. Ambassador to the United Kingdom 1936–1938. Minister of Foreign Affairs 1938–1945.[20] |

Alfred Rosenberg | G | G | G | G | Death | Racial theory ideologist. Later, Minister of the Eastern Occupied Territories 1941–1945.[21] |

Fritz Sauckel | I | I | G | G | Death | Gauleiter of Thuringia 1927–1945. Plenipotentiary of the Nazi slave labor program 1942–1945.[22] |

Dr. Hjalmar Schacht | I | I | O | O | Acquitted | Prominent banker and economist. President of the Reichsbank 1923–1930 and 1933–1938 and Economics Minister 1934–1937. Admitted breaking the Treaty of Versailles.[23] |

Baldur von Schirach (standing) | I | O | O | G | 20 years | Head of the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) from 1933 to 1940, Gauleiter of Vienna 1940–1943. Expressed sorrow.[24] |

Arthur Seyß-Inquart | I | G | G | G | Death | Helped the Anschluß (joining Germany and Austria). Was briefly the Austrian Chancellor 1938. Deputy to Frank in Poland 1939–1940. Later, Reich Commissioner of the occupied Netherlands 1940–1945. Expressed sorrow.[25] |

Albert Speer | I | I | G | G | 20 Years | Hitler’s favourite architect, personal friend, and Minister of Armaments from 1942. As Minister of Armaments, he used slave labour from the occupied territories in weapons production. Expressed sorrow.[26] |

Julius Streicher | I | O | O | G | Death | Gauleiter of Franconia 1922–1945. Incited hatred and murder against the Jews through his weekly newspaper, Der Stürmer.[27] |

“I” indicted “G” indicted and found guilty “O” Not Charged

The Allies also tried seven Nazi organizations at Nuremberg:[28]

The death sentences were carried out on 16 October 1946 by hanging using the inefficient American “standard” drop method instead of the long drop.[30][31] The executioner was John C. Woods. The French judges suggested the use of a firing squad for the convicted military officials, as is standard for military courts-martial. However, Biddle and the Soviet judges did not agree. They said that the military officers acted so badly that they did not deserve to be treated as soldiers.

The prisoners sentenced to imprisonment were transferred to Spandau Prison in 1947.

Nuremberg principles is a document created as a result of the trial. It defines what a war crime is.

The medical experiments conducted by German doctors and prosecuted in the so-called Doctors’ Trial led to the creation of the Nuremberg Code to control future trials involving human subjects.

The Nuremberg executions took place on the early morning of October 16, 1946, shortly after the conclusion of the Nuremberg trials. Ten prominent members of the political and military leadership of Nazi Germany were executed by hanging: Hans Frank, Wilhelm Frick, Alfred Jodl, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Wilhelm Keitel, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Alfred Rosenberg, Fritz Sauckel, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, and Julius Streicher. Hermann Göring was also scheduled to be hanged on that day, but committed suicide using a potassium cyanide capsule the night before. Martin Bormann was also sentenced to death in absentia; at the time, his whereabouts were unknown, but it has since been confirmed that he died while attempting to escape Berlin on May 2, 1945.

For their last meal, the condemned men were served sausage and cold cuts, along with potato salad and black bread, and were given tea to drink. Starting at approximately 1:10 am, they were led one at a time to the execution chamber to be hanged. The death sentences were carried out in the gymnasium of Nuremberg Prison by the United States Army using the standard drop method (instead of the long drop method favored by British executioners). Three temporary gallows had been erected in the gymnasium, with the execution team using two in alternating order and reserving the remaining gallows as a spare.

The executioners were Master Sergeant John C. Woods and his assistant, military policeman Joseph Malta. Woods’s use of standard drops for the executions meant that some of the men did not die quickly of an intended broken neck but instead strangled to death slowly. Some reports indicated some executions took from 14 to 28 minutes. The Army denied claims that the drop length was too short or that the condemned died from strangulation instead of a broken neck. Additionally, the trapdoor was too small, such that several of the condemned suffered bleeding head injuries when they hit the sides of the trapdoor while dropping through. The bodies were rumored to have been taken to Dachau for cremation but were incinerated in a crematorium in Munich and the ashes scattered over the river Isar.

Kingsbury Smith of the International News Service wrote an eyewitness account of the hangings. His account, accompanied by photos, appeared in newspapers.

Footnote

Do not miss Russell Crowe new film about these trials. He plays the part of Hermann Goering who cheated the hangman by taking cyanide pill on hearing his sentence. The film comes out on Saturday 15th November 2025.

“I recently used my new washing machine for the first time and have now familiarized myself with its operation. To access the user instructions, it is necessary to scan the code located on the machine.” I am really pleased with myself given I have a Learning Disability. This is all about promoting that we can lead constructive lives and manage day-to-day activities.

Doxxing happens when someone shares your private information online without your consent. It’s an invasive and sometimes dangerous act that can lead to harassment or worse. While stories of celebrities and influencers being doxxed often make headlines, this isn’t just their problem. Everyday people can be targeted too. In fact, over 11 million Americans were doxxed in 2024 alone, according to a SafeHome study.

https://www.cyberghostvpn.com/privacyhub/what-is-doxxing-why-dangerous-how-to-avoid

I am booking my visit to Santas grotto in Newcastle

During World War I, the German Empire was one of the Central Powers. It began participation in the conflict after the declaration of war against Serbia by its ally, Austria-Hungary. German forces fought the Allies on both the eastern and western fronts, although German territory itself remained relatively safe from widespread invasion for most of the war, except for a brief period in 1914 when East Prussia was invaded. A tight blockade imposed by the Royal Navy caused severe food shortages in the cities, especially in the winter of 1916–17, known as the Turnip Winter. At the end of the war, Germany’s defeat and widespread popular discontent triggered the German Revolution of 1918–1919 which overthrew the monarchy and established the Weimar Republic.

Main articles: German entry into World War I and German Empire § World War I

Germany’s population had already responded to the outbreak of war in 1914 with a complex mix of emotions, in a similar way to the emotions of the population in the United Kingdom; notions of universal enthusiasm known as the Spirit of 1914 have been challenged by more recent scholarship. The German government, dominated by the Junkers, saw the war as a way to end being surrounded by hostile powers France, Russia and Britain. The war was presented inside Germany as the chance for the nation to secure “our place under the sun,” as the Foreign Minister Bernhard von Bülow had put it, which was readily supported by prevalent nationalism among the public. The German establishment hoped the war would unite the public behind the monarchy, and lessen the threat posed by the dramatic growth of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, which had been the most vocal critic of the Kaiser in the Reichstag before the war. Despite its membership in the Second International, the Social Democratic Party of Germany ended its differences with the Imperial government and abandoned its principles of internationalism to support the war effort. The German state spent 170 billion Marks during the war. The money was raised by borrowing from banks and from public bond drives. Symbolic purchasing of nails which were driven into public wooden crosses spurred the aristocracy and middle class to buy bonds. These bonds became worthless with the 1923 hyperinflation.

It soon became apparent that Germany was not prepared for a war lasting more than a few months. At first, little was done to regulate the economy on a wartime footing, and the German war economy would remain badly organized throughout the war. The country depended on imports of food and raw materials, which were stopped by the British blockade of Germany. First food prices were limited, then rationing was introduced. The winter of 1916/17 was called the “turnip winter” because the potato harvest was poor and people ate animal food, including vile-tasting turnips. From August 1914 to mid-1919, excess deaths compared to peacetime caused by malnutrition and high rates of exhaustion and disease and despair came to about 474,000 civilians excluding “Alsace-Lorraine and the Polish provinces”.

Main article: German entry into World War I

According to the biographer, Konrad H. Jarausch, a primary concern for Bethmann Hollweg in July 1914 was the steady growth of Russian power and the growth of British and French military collaboration. Under these circumstances he decided to run what he considered a calculated risk to back Vienna in a local war against Serbia, while risking a big war with Russia. He calculated that France would not support Russia. It failed when Russia decided on general mobilization. By rushing through Belgium, Germany expanded the war to include England. Bethmann Hollweg thus failed to keep France and Britain out of the conflict.

The crisis came to a head on 5 July 1914 when Count Hoyos Mission arrived in Berlin in response to Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold‘s plea for friendship. Bethmann Hollweg was assured that Britain would not intervene in the frantic diplomatic rounds across the European powers. Reliance on that assumption encouraged Austria to demand Serbian concessions. His main concern was Russian border manoeuvres, conveyed by his ambassadors at a time when Raymond Poincaré himself was preparing a secret mission to St Petersburg. He wrote to Count Sergey Sazonov, “Russian mobilisation measures would compel us to mobilise and that then European war could scarcely be prevented.”

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, Bethmann Hollweg and his foreign minister, Gottlieb von Jagow, were instrumental in assuring Austria-Hungary of Germany’s unconditional support, regardless of Austria’s actions against Serbia. While Grey was suggesting mediation between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, Bethmann Hollweg wanted Austria-Hungary to attack Serbia and so he tampered with the British message and deleted the last line of the letter: “Also, the whole world here is convinced, and I hear from my colleagues that the key to the situation lies in Berlin, and that if Berlin seriously wants peace, it will prevent Vienna from following a foolhardy policy.

When the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum was presented to Serbia, Kaiser Wilhelm II ended his vacation and hurried back to Berlin.

When Wilhelm arrived at the Potsdam station late in the evening of July 26, he was met by a pale, agitated, and somewhat fearful Chancellor. Bethmann Hollweg’s apprehension stemmed not from the dangers of the looming war, but rather from his fear of the Kaiser’s wrath when the extent of his deceptions were revealed. The Kaiser’s first words to him were suitably brusque: “How did it all happen?” Rather than attempt to explain, the Chancellor offered his resignation by way of apology. Wilhelm refused to accept it, muttering furiously, “You’ve made this stew, now you’re going to eat it!”

Bethmann Hollweg, much of whose foreign policy before the war had been guided by his desire to establish good relations with Britain, was particularly upset by Britain’s declaration of war following the German violation of Belgium’s neutrality during its invasion of France. He reportedly asked the departing British Ambassador Edward Goschen how Britain could go to war over a “scrap of paper” (“ein Fetzen Papier“), which was the 1839 Treaty of London guaranteeing Belgium’s neutrality.

Bethmann Hollweg sought public approval from a declaration of war. His civilian colleagues pleaded for him to register some febrile protest, but he was frequently outflanked by the military leaders, who played an increasingly important role in the direction of all German policy.[9] However, according to historian Fritz Fischer, writing in the 1960s, Bethmann Hollweg made more concessions to the nationalist right than had previously been thought. He supported the ethnic cleansing of Poles from the Polish Border Strip as well as Germanisation of Polish territories by settlement of German colonists.

A few weeks after the war began Bethmann presented the Septemberprogramm, which was a survey of ideas from the elite should Germany win the war. Bethmann Hollweg, with all credibility and power now lost, conspired over Falkenhayn’s head with Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff (respectively commander-in-chief and chief of staff for the Eastern Front) for an Eastern Offensive. They then succeeded, in August 1916 in securing Falkenhayn’s replacement by Hindenburg as Chief of the General Staff, with Ludendorff as First Quartermaster-General (Hindenburg’s deputy). Thereafter, Bethmann Hollweg’s hopes for US President Woodrow Wilson‘s mediation at the end of 1916 came to nothing. Over Bethmann Hollweg’s objections, Hindenburg and Ludendorff forced the adoption of unrestricted submarine warfare in March 1917, adopted as a result of Henning von Holtzendorff‘s memorandum. Bethmann Hollweg had been a reluctant participant and opposed it in cabinet. The US entered the war in April 1917.

According to Wolfgang J. Mommsen, Bethmann Hollweg weakened his position by failing to establish good control over public relations. To avoid highly intensive negative publicity, he conducted much of his diplomacy in secret, thereby failing to build strong support for it. In 1914 he was willing to risk a world war to win public support. Bethmann Hollweg remained in office until July 1917, when a Reichstag revolt resulted in the passage of Matthias Erzberger‘s Peace Resolution by an alliance of the Social Democratic, Progressive, and Centre parties. Opposition to him from high-level military leaders, including Hindenburg and Ludendorff, who both threatened to resign was exacerbated when Bethmann Hollweg convinced the Emperor to agree publicly to the introduction of equal male suffrage in Prussian state elections. The combination of political and military opposition forced Bethmann Hollweg’s resignation and replacement by Georg Michaelis.

Main article: Western Front (World War I)

The German army opened the war on the Western Front with a modified version of the Schlieffen Plan, designed to quickly attack France through neutral Belgium before turning southwards to encircle the French army on the German border. The Belgians fought back, and sabotaged their rail system to delay the Germans. The Germans did not expect this and were delayed, and responded with systematic reprisals on civilians, killing nearly 6,000 Belgian noncombatants, including women and children, and burning 25,000 houses and buildings. The plan called for the right flank of the German advance to converge on Paris and initially, the Germans were very successful, particularly in the Battle of the Frontiers (14–24 August). By 12 September, the French with assistance from the British forces halted the German advance east of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September). The last days of this battle signified the end of mobile warfare in the west. The French offensive into Germany launched on 7 August with the Battle of Mulhouse had limited success.

In the east, only one Field Army defended East Prussia and when Russia attacked in this region it diverted German forces intended for the Western Front. Germany defeated Russia in a series of battles collectively known as the First Battle of Tannenberg (17 August – 2 September), but this diversion exacerbated problems of insufficient speed of advance from rail-heads not foreseen by the German General Staff. The Central Powers were thereby denied a quick victory and forced to fight a war on two fronts. The German army had fought its way into a good defensive position inside France and had permanently incapacitated 230,000 more French and British troops than it had lost itself. Despite this, communications problems and questionable command decisions cost Germany the chance of obtaining an early victory.

1916 was characterized by two great battles on the Western front, at Verdun and the Somme. They each lasted most of the year, achieved minimal gains, and drained away the best soldiers of both sides. Verdun became the iconic symbol of the murderous power of modern defensive weapons, with 280,000 German casualties, and 315,000 French. At the Somme, there were over 400,000 German casualties, against over 600,000 Allied casualties. At Verdun, the Germans attacked what they considered to be a weak French salient which nevertheless the French would defend for reasons of national pride. The Somme was part of a multinational plan of the Allies to attack on different fronts simultaneously. German woes were also compounded by Russia’s grand “Brusilov offensive”, which diverted more soldiers and resources. Although the Eastern front was held to a standoff and Germany suffered fewer casualties than their allies with ~150,000 of the ~770,000 Central powers casualties, the simultaneous Verdun offensive stretched the German forces committed to the Somme offensive. German experts are divided in their interpretation of the Somme. Some say it was a stand-off, but most see it as a British victory and argue it marked the point at which German morale began a permanent decline and the strategic initiative was lost, along with irreplaceable veterans and confidence.

See also: Berlin Conference (March 31, 1917)

In early 1917 the SPD leadership became concerned about the activity of its anti-war left-wing which had been organising as the Sozialdemokratische Arbeitsgemeinschaft (SAG, “Social Democratic Working Group”). On 17 January they expelled them, and in April 1917 the left wing went on to form the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (German: Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands). The remaining faction was then known as the Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany. This happened as the enthusiasm for war was fading in light of the enormous numbers of casualties, the dwindling supply of manpower, the mounting difficulties on the home front, and the never-ending flow of casualty reports. A grimmer and grimmer attitude began to prevail amongst the general population. The only highlight was the first use of mustard gas in warfare, in the Battle of Ypres.

Subsequently, morale was helped by victories against Serbia, Greece, Italy and Russia, which constituted great gains for the Central Powers. Morale was at its greatest since 1914 at the end of 1917 and beginning of 1918, with the defeat of Russia following her uprising in revolution, and the German people braced themselves for what General Erich Ludendorff said would be the “Peace Offensive” in the west.

Further information: German spring offensive

In spring 1918, Germany realized that time was running out. It prepared for the decisive strike with new armies and new tactics, hoping to win the war on the Western front before millions of American soldiers appeared in battle. General Erich Ludendorff and Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg had full control of the army, they had a large supply of reinforcements moved from the Eastern front, and they trained storm troopers with new tactics to race through the trenches and attack the enemy’s command and communications centers. The new tactics would indeed restore mobility to the Western front, but the German army was over-optimistic.

During the winter of 1917-18 it was “quiet” on the Western Front—British casualties averaged “only” 3,000 a week. Serious attacks were impossible in the winter because of the deep caramel-thick mud. Quietly the Germans brought in their best soldiers from the eastern front, selected elite storm troops, and trained them all winter long in the new tactics. With stopwatch timing, the German artillery would lay down a sudden, fearsome barrage just ahead of its advancing infantry. Moving in small units, firing light machine guns, the stormtroopers would bypass enemy strong points, and head directly for critical bridges, command posts, supply dumps and, above all, artillery batteries. By cutting enemy communications they would paralyze response in the critical first half hour. By silencing the artillery they would break the enemy’s firepower. Rigid schedules sent in two more waves of infantry to mop up the strong points that had been bypassed. The shock troops frightened and disoriented the first line of defenders, who would flee in panic. In one instance an easy-going Allied regiment broke and fled; reinforcements rushed in on bicycles. The panicky soldiers seized the bikes and beat an even faster retreat. The stormtrooper tactics provided mobility, but not increased firepower. Eventually—in 1939 and 1940—the formula would be perfected with the aid of dive bombers and tanks, but in 1918 the Germans as yet lacked both.

Ludendorff erred by attacking the British first in 1918, instead of the French. He mistakenly thought the British to be too uninspired to respond rapidly to the new tactics. The exhausted, dispirited French perhaps might have folded. The German assaults on the British were ferocious—the most extensive of the entire war. At the Somme River in March, 63 divisions attacked in a blinding fog. No matter, the German lieutenants had memorized their maps and their orders. The British lost 270,000 men, fell back 40 miles, and then held. They quickly learned how to handle the new German tactics: fall back, abandon the trenches, let the attackers overextend themselves, and then counterattack. They gained an advantage in firepower from their artillery and from tanks used as mobile pillboxes that could retreat and counterattack at will. In April Ludendorff hit the British again, inflicting 305,000 casualties—but he lacked the reserves to follow up. In total, Ludendorff launched five major attacks between March and July, inflicting a million British and French casualties. The Western Front now had opened up—the trenches were still there but the importance of mobility now reasserted itself. The Allies held. The Germans suffered twice as many casualties as they inflicted, including most of their precious stormtroopers. The new German replacements were under-aged youth or embittered middle-aged family men in poor condition. They were not inspired by the enthusiasm of 1914, nor thrilled with battle—they hated it, and some began talking of revolution. Ludendorff could not replace his losses, nor could he devise a new brainstorm that might somehow snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. The British likewise were bringing in reinforcements from the whole Empire, but since their home front was in good condition and they could sight inevitable victory, their morale was higher. The great German spring offensive was a race against time, for everyone could see the Americans were training millions of fresh soldiers who would eventually arrive on the Western Front.

The attrition warfare now caught up to both sides. Germany had used up all the best soldiers they had, and still had not conquered much territory. The British likewise were bringing in youths of 18 and unfit and middle-aged men, but they could see the Americans arriving steadily. The French had also nearly exhausted their manpower. Berlin had calculated it would take months for the Americans to ship all their soldiers and equipment—but the U.S. troops arrived much sooner, as they left their heavy equipment behind, and relied on British and French artillery, tanks, airplanes, trucks and equipment. Berlin also assumed that Americans were fat, undisciplined and unaccustomed to hardship and severe fighting. They soon realized their mistake. The Germans reported that “[t]he qualities of the [Americans] individually may be described as remarkable. They are physically well set up, their attitude is good… They lack at present only training and experience to make formidable adversaries. The men are in fine spirits and are filled with naive assurance.”

By September 1918, the Central Powers were exhausted from fighting, the American forces were pouring into France at a rate of 10,000 a day, the British Empire was mobilised for war peaking at 4.5 million soldiers and 4,000 tanks on the Western Front. The decisive Allied counteroffensive, known as the Hundred Days Offensive, began on 8 August 1918—what Ludendorff called the “Black Day of the German army.” The Allied armies advanced steadily as German defenses faltered.

Although German armies were still on enemy soil as the war ended, the generals, the civilian leadership—and indeed the soldiers and the people—knew all was hopeless. They started looking for scapegoats. The hunger and popular dissatisfaction with the war precipitated revolution throughout Germany. By 11 November Germany had virtually surrendered, the Kaiser and all the royal families had abdicated, and the German Empire fell.

The “spirit of 1914” was the enthusiastic support of mostly the educated middle- and upper-class elements of the population for the war when it first broke out in 1914. In the Reichstag, the vote for credits was unanimous, including from the Social Democrats. One professor testified to a “great single feeling of moral elevation or soaring of religious sentiment, in short, the ascent of a whole people to the heights.” At the same time, there was a level of anxiety; most commentators predicted a short victorious war – but that hope was dashed in a matter of weeks, as the invasion of Belgium bogged down and the French Army held before Paris. The Western Front became a killing machine, as neither army moved more than a few hundred yards at a time. Industry in late 1914 was in chaos, unemployment soared while it took months to reconvert to munitions productions. In 1916, the Hindenburg Program called for the mobilization of all economic resources to produce artillery, shells, and machine guns. Church bells and copper roofs were ripped out and melted down.

According to historian William H. MacNeil:By 1917, after three years of war, the various groups and bureaucratic hierarchies which had been operating more or less independently of one another in peacetime (and not infrequently had worked at cross-purposes) were subordinated to one (and perhaps the most effective) of their number: the General Staff. Military officers controlled civilian government officials, the staffs of banks, cartels, firms, and factories, engineers and scientists, working men, farmers – indeed almost every element in German society; and all efforts were directed in theory, and in large degree also in practice, to forwarding the war effort.

Germany had no plans for mobilizing its civilian economy for the war effort, and no stockpiles of food or critical supplies had been made. Germany had to improvise rapidly. All major political sectors initially supported the war, including the Socialists.

Early in the war industrialist Walther Rathenau held senior posts in the Raw Materials Department of the War Ministry, while becoming chairman of AEG upon his father’s death in 1915. Rathenau played the key role in convincing the War Ministry to set up the War Raw Materials Department (Kriegsrohstoffabteilung – ‘KRA’); he was in charge of it from August 1914 to March 1915 and established the basic policies and procedures. His senior staff were on loan from industry. KRA focused on raw materials threatened by the British blockade, as well as supplies from occupied Belgium and France. It set prices and regulated the distribution to vital war industries. It began the development of ersatz raw materials. KRA suffered many inefficiencies caused by the complexity and selfishness KRA encountered from commerce, industry, and the government.

While the KRA handled critical raw materials, the crisis over food supplies grew worse. The mobilization of so many farmers and horses, and the shortages of fertilizer, steadily reduced the food supply. Prisoners of war were sent to work on farms, and many women and elderly men took on work roles. Supplies that had once come in from Russia and Austria were cut off.

The concept of “total war” in World War I, meant that food supplies had to be redirected towards the armed forces and, with German commerce being stopped by the British blockade, German civilians were forced to live in increasingly meagre conditions. Food prices were first controlled. Bread rationing was introduced in 1915 and worked well; the cost of bread fell. Keith Allen says there were no signs of starvation and states, “the sense of domestic catastrophe one gains from most accounts of food rationing in Germany is exaggerated.” However, Howard argues that hundreds of thousands of civilians died from malnutrition—usually from typhus or a disease that their weakened body could not resist. (Starvation itself rarely caused death.) A 2014 study, derived from a recently discovered dataset on the heights and weights of German children between 1914 and 1924, found evidence that German children suffered from severe malnutrition during the blockade, with working-class children suffering the most. The study furthermore found that German children quickly recovered after the war due to a massive international food aid program.

Conditions deteriorated rapidly on the home front, with severe food shortages reported in all urban areas. The causes involved the transfer of so many farmers and food workers into the military, combined with the overburdened railroad system, shortages of coal, and the British blockade, which cut off imports from abroad. The winter of 1916–1917 was known as the “turnip winter,” because that hardly-edible vegetable, usually fed to livestock, was used by people as a substitute for potatoes and meat, which were increasingly scarce. Thousands of soup kitchens were opened to feed the hungry people, who grumbled that the farmers were keeping the food for themselves. Even the army had to cut the rations for soldiers. Morale of both civilians and soldiers continued to sink.

The drafting of miners reduced the main energy source, coal. The textile factories produced army uniforms, and warm clothing for civilians ran short. The device of using ersatz materials, such as paper and cardboard for cloth and leather proved unsatisfactory. Soap was in short supply, as was hot water. All cities reduced tram services, cut back on street lighting, and closed down theaters and cabarets.

The food supply increasingly focused on potatoes and bread, it was harder and harder to buy meat. The meat ration in late 1916 was only 31% of peacetime, and it fell to 12% in late 1918. The fish ration was 51% in 1916, and none at all by late 1917. The rations for cheese, butter, rice, cereals, eggs and lard were less than 20% of peacetime levels. In 1917 the harvest was poor all across Europe, and the potato supply ran short, and Germans substituted almost inedible turnips; the “Turnip Winter” of 1916–17 was remembered with bitter distaste for generations. Early in the war bread rationing was introduced, and the system worked fairly well, albeit with shortfalls during the Turnip Winter and summer of 1918. White bread used imported flour and became unavailable, but there was enough rye or rye-potato flour to provide a minimal diet for all civilians.

German women were not employed in the Army, but large numbers took paid employment in industry and factories, and even larger numbers engaged in volunteer services. Housewives were taught how to cook without milk, eggs or fat; agencies helped widows find work. Banks, insurance companies and government offices for the first time hired women for clerical positions. Factories hired them for unskilled labor – by December 1917, half the workers in chemicals, metals, and machine tools were women. Laws protecting women in the workplace were relaxed, and factories set up canteens to provide food for their workers, lest their productivity fall off. The food situation in 1918 was better, because the harvest was better, but serious shortages continued, with high prices, and a complete lack of condiments and fresh fruit. Many migrants had flocked into cities to work in industry, which made for overcrowded housing. Reduced coal supplies left everyone in the cold. Daily life involved long working hours, poor health, and little or no recreation, and increasing fears for the safety of loved ones in the Army and in prisoner-of-war camps. The men who returned from the front were those who had been permanently disabled; wounded soldiers who had recovered were sent back to the trenches.

See also: Aftermath of World War I

Many Germans wanted an end to the war and increasing numbers of Germans began to associate with the political left, such as the Social Democratic Party and the more radical Independent Social Democratic Party which demanded an end to the war. The third reason was the entry of the United States into the war in April 1917, which tipped the long-run balance of power even more to the Allies. The end of October 1918, in Kiel, in northern Germany, saw the beginning of the German Revolution of 1918–19. Sailors mutinied at the prospect of a final battle against the British Navy, and by means of workers’ and soldiers’ councils, they quickly spread the revolt across Germany. Meanwhile, Hindenburg and the senior generals lost confidence in the Kaiser and his government.

In November 1918, with internal revolution, a stalemated war, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire suing for peace, Austria-Hungary falling apart from multiple ethnic tensions, and pressure from the German High Command and the workers’ and soldiers’ councils, the Kaiser and all German ruling princes abdicated. On 9 November 1918, the Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed a Republic. The new government led by the German Social Democrats called for and received an armistice on 11 November 1918; in practice it was a surrender, and the Allies kept up the food blockade to guarantee an upper hand in negotiations. The now defunct German Empire had gotten so defunct that it fell and France took all of the empire.

7 million soldiers and sailors were quickly demobilized. Some joined right-wing organizations such as the Freikorps; radicals or the far Left helped form the Communist Party of Germany.

Due to German military forces still occupying portions of France on the day of the armistice, various nationalist groups and those angered by the defeat in the war shifted blame to civilians; accusing them of betraying the army and surrendering. This contributed to the “Stab-in-the-back myth” that dominated the French occupied German government.

Main article: World War I casualties

Out of a population of 65 million, Germany suffered 1.7 million military deaths and 430,000 civilian deaths due to wartime causes (especially the food blockade), plus about 17,000 killed in Africa and the other overseas colonies.

The Allied blockade continued until July 1919, causing severe additional hardships.

Despite the often ruthless conduct of the German military machine, in the air and at sea as well as on land, individual German and soldiers could view the enemy with respect and empathy and the war with contempt. Some examples from letters homeward:

“A terrible picture presented itself to me. A French and a German soldier on their knees were leaning against each other. They had pierced each other with the bayonet and had dropped like this to the ground…Courage, heroism, does it really exist? I am about to doubt it, since I haven’t seen anything else than fear, anxiety, and despair in every face during the battle. There was nothing at all like courage, bravery, or the like. In reality, there is nothing else than texting discipline and coercion propelling the soldiers forward” Dominik Richert, 1914.

“Our men have reached an agreement with the French to cease fire. They bring us bread, wine, sardines etc., we bring them schnapps. The masters make war, they have a quarrel, and the workers, the little men…have to stand there fighting against each other. Is that not a great stupidity?…If this were to be decided according to the number of votes, we would have been long home by now” Hermann Baur, 1915.

“I have no idea what we are still fighting for anyway, maybe because the newspapers portray everything about the war in a false light which has nothing to do with the reality…..There could be no greater misery in the enemy country and at home. The people who still support the war haven’t got a clue about anything…If I stay alive, I will make these things public…We all want peace…What is the point of conquering half of the world, when we have to sacrifice all our strength?..You out there, just champion peace! … We give away all our worldly possessions and even our freedom. Our only goal is to be with our wife and children again,” Anonymous Bavarian soldier, 17 October 1914.

The Hitler cabinet was the government of Nazi Germany between 30 January 1933 and 30 April 1945 upon the appointment of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany by President Paul von Hindenburg. It was contrived by the national conservative politician Franz von Papen, who reserved the office of the Vice-Chancellor for himself. Originally, Hitler’s first cabinet was called the Reich Cabinet of National Salvation, which was a coalition of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and the national conservative German National People’s Party (DNVP). The Hitler cabinet lasted until his suicide during the defeat of Nazi Germany. Hitler’s cabinet was succeeded by the short-lived Goebbels cabinet, with Karl Dönitz appointed by Hitler as the new Reichspräsident.

In brokering the appointment of Hitler as Reich Chancellor, Papen had sought to control Hitler by limiting the number of Nazi ministers in the cabinet; initially Hermann Göring (without portfolio) and Wilhelm Frick (Interior) were the only Nazi ministers. Further, Alfred Hugenberg, the head of the DNVP, was enticed into joining the cabinet by being given the Economic and Agricultural portfolios for both the Reich and Prussia, with the expectation that Hugenberg would be a counterweight to Hitler and would be useful in controlling him. Of the other significant ministers in the initial cabinet, Foreign Minister Konstantin von Neurath was a holdover from the previous administration, as were Finance Minister Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk, Post and Transport Minister Paul Freiherr von Eltz-Rübenach, and Justice Minister Franz Gürtner.

The cabinet was “presidential” and not “parliamentary”, in that it governed on the basis of emergency powers granted to the President in Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution rather than through a majority vote in the Reichstag. This had been the basis for Weimar cabinets since Hindenburg’s appointment of Heinrich Brüning as Chancellor in March 1930. Hindenburg specifically wanted a cabinet of the nationalist right, without participation by the Catholic Centre Party or the Social Democratic Party, which had been the mainstays of earlier parliamentary cabinets. Hindenburg turned to Papen, a former Chancellor himself, to bring such a body together, but blanched at appointing Hitler as Chancellor. Papen was certain that Hitler and the Nazi Party had to be included, but Hitler had previously turned down the position of Vice Chancellor. So Papen, with the help of Hindenburg’s son Oskar, persuaded Hindenburg to appoint Hitler Chancellor.

Initially, the Hitler cabinet, like its immediate predecessors, ruled through Presidential decrees written by the cabinet and signed by Hindenburg. However, the Enabling Act of 1933, passed two months after Hitler took office, gave the cabinet the power to make laws without legislative consent or Hindenburg’s signature. In effect, the power to rule by decree was vested in Hitler, and for all intents and purposes it made him a dictator. After the Enabling Act’s passage, serious deliberations more or less ended at cabinet meetings. It met only sporadically after 1934, and last met in full on 5 February 1938.

When Hitler came to power, the cabinet consisted of the Chancellor, the Vice-Chancellor and the heads of 10 Reich Ministries. Between 1933 and 1941 six new Reichsministries were established, but the War Ministry was abolished and replaced by the OKW. The cabinet was further enlarged by the addition of several Reichsministers without Portfolio and by other officials, such as the commanders-in-chief of the armed services, who were granted the rank and authority of Reichsministers but without the title. In addition, various officials – though not formally Reichsministers – such as Reich Youth Leader Baldur von Schirach, Prussian Finance Minister Johannes Popitz, and Chief of the Organisation for Germans Abroad, Ernst Wilhelm Bohle, were authorised to participate in Reich cabinet meetings when issues within their area of jurisdiction were under discussion.

As the Nazis consolidated political power, other parties were outlawed or dissolved themselves. Of the three original DNVP ministers, Franz Seldte joined the Nazi Party in April 1933, Hugenberg departed the cabinet in June when the DNVP was dissolved and Gürtner stayed on without a party designation. There were originally several other independent politicians in the cabinet, mainly holdovers from previous governments. Gereke was the first of these to be dismissed when he was arrested for embezzlement on 23 March 1933. Papen was then dismissed in early August 1934. Then, on 30 January 1937, Hitler presented the Golden Party Badge to all remaining non-Nazi members of the cabinet (Blomberg, Eltz-Rübenach, Fritsch, Gürtner, Neurath, Raeder & Schacht) and enrolled them in the Party. Only Eltz-Rübenach, a devout Roman Catholic, refused and resigned. Similarly, on 20 April 1939, Brauchitsh and Keitel were presented with the Golden Party Badge. Dorpmüller received it in December 1940 and formally joined the Party on 1 February 1941. Dönitz followed on 30 January 1944. Thus, no independent politicians or military leaders were left in the cabinet.

The actual power of the cabinet as a body was minimised when it stopped meeting in person and decrees were worked out between the ministries by sharing and marking-up draft proposals, which only went to Hitler for rejection, revision or signing when that process was completed. The cabinet was also overshadowed by the numerous ad hoc agencies – both of the state and of the Nazi Party – such as Supreme Reich Authorities and plenipotentiaries – that Hitler caused to be created to deal with specific problems and situations. Individual ministers, however, especially Göring, Goebbels, Himmler, Speer, and Bormann, held extensive power, at least until, in the case of Göring and Speer, Hitler came to distrust them.

By the final years of World War II, Bormann had emerged as the most powerful minister, not because he was head of the Party Chancellery, which was the basis of his position in the cabinet, but because of his control of access to Hitler in his role as Secretary to the Führer.

Paul Joseph Goebbels (German: 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician and philologist who was the Gauleiter (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 1945. He was one of Adolf Hitler‘s closest and most devoted followers, known for his skills in public speaking and his virulent antisemitism which was evident in his publicly voiced views. He advocated progressively harsher discrimination, including the extermination of Jews and other groups in the Holocaust.

Goebbels, who aspired to be an author, obtained a doctorate in philology from the University of Heidelberg in 1922. He joined the Nazi Party in 1924 and worked with Gregor Strasser in its northern branch. He was appointed Gauleiter of Berlin in 1926, where he began to take an interest in the use of propaganda to promote the party and its programme. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Goebbels’s Propaganda Ministry quickly gained control over the news media, arts and information in Nazi Germany. He was particularly adept at using the relatively new media of radio and film for propaganda purposes. Topics for party propaganda included antisemitism, attacks on Christian churches, and (after the start of the Second World War) attempts to shape morale.

In 1943, Goebbels began to pressure Hitler to introduce measures that would produce “total war“, including closing businesses not essential to the war effort, conscripting women into the labour force, and enlisting men in previously exempt occupations into the Wehrmacht. Hitler finally appointed him as Reich Plenipotentiary for Total War on 23 July 1944, whereby Goebbels undertook largely unsuccessful measures to increase the number of people available for armaments manufacture and the Wehrmacht.

As the war drew to a close and Nazi Germany faced defeat, Magda Goebbels and the Goebbels children joined Hitler in Berlin. They moved into the underground Vorbunker, part of Hitler’s underground bunker complex, on 22 April 1945. Hitler committed suicide on 30 April. In accordance with Hitler’s will, Goebbels succeeded him as Chancellor of Germany; he served one day in this post. The following day, Goebbels and his wife, Magda, committed suicide, after having poisoned their six children with a cyanide compound.

Paul Joseph Goebbels was born on 29 October 1897 in Rheydt, an industrial town south of Mönchengladbach near Düsseldorf, Germany. Both of his parents were Roman Catholics with modest family backgrounds. His father, Fritz, was a German factory clerk; his mother, Katharina Maria (née Odenhausen), was born to Dutch and German parents in a Dutch village close to the border with Germany. Goebbels had five siblings: Konrad (1893–1949), Hans (1895–1947), Maria (1896–1896), Elisabeth (1901–1915) and Maria (1910–1949), who married the German filmmaker Max W. Kimmich in 1938. In 1932 Goebbels commissioned the publication of a pamphlet of his family tree to refute the rumours that his maternal grandmother was of Jewish ancestry.

During childhood Goebbels experienced ill health, which included a long bout of inflammation of the lungs. He had a deformed right foot, which turned inwards due to a congenital disorder or an infection in the bone. It was thicker and shorter than his left foot. Just prior to starting grammar school he underwent an operation, which failed to correct the problem. Goebbels wore a metal brace and a special shoe because of his shortened leg and walked with a limp. He was rejected for military service in World War I because of this condition.

Goebbels was educated at a Gymnasium, where he completed his Abitur (university entrance examination) in 1917. He was the top student of his class and was given the traditional honour of speaking at the awards ceremony. His parents initially hoped that he would become a Catholic priest, which Goebbels seriously considered. He studied literature and history at the universities of Bonn, Würzburg, Freiburg and Munich, aided by a scholarship from the Albertus Magnus Society. By this time Goebbels had begun to distance himself from the church.

Historians, including Richard J. Evans and Roger Manvell, speculate that Goebbels’ lifelong pursuit of women may have been in compensation for his physical disability. At Freiburg he met and fell in love with Anka Stalherm, who was three years his senior. She went on to Würzburg to continue studying, as did Goebbels By 1920 the relationship with Anka was over; the break-up filled Goebbels with thoughts of suicide. In 1921 he wrote a semi-autobiographical novel, Michael, a three-part work of which only Parts I and III have survived. Goebbels felt he was writing his “own story”. Antisemitic content and material about a charismatic leader may have been added by Goebbels shortly before the book was published in 1929 by Eher-Verlag, the publishing house of the Nazi Party (National Socialist German Workers’ Party; NSDAP).

At the University of Heidelberg Goebbels wrote his doctoral thesis on Wilhelm von Schütz, a minor 19th-century romantic dramatist. He had hoped to write his thesis under the supervision of Friedrich Gundolf, a literary historian. It did not seem to bother Goebbels that Gundolf was Jewish. As he was no longer teaching, Gundolf directed Goebbels to associate professor Max Freiherr von Waldberg. Waldberg, who was also Jewish, recommended Goebbels write his thesis on Wilhelm von Schütz. After submitting the thesis and passing his oral examination, Goebbels received his PhD on 21 April 1922. By 1940 he had written 14 books.

Goebbels returned home and worked as a private tutor. He also found work as a journalist and was published in the local newspaper. His writing during that time reflected his growing antisemitism and dislike for modern culture. In the summer of 1922 he met and began a love affair with Else Janke, a schoolteacher. After she revealed to him that she was half-Jewish, Goebbels stated the “enchantment [was] ruined.” Nevertheless he continued to see her on and off until 1927.

He continued for several years to try to become a published author. His diaries, which he began in 1923 and continued for the rest of his life, provided an outlet for his desire to write. The lack of income from his literary works – he wrote two plays in 1923, neither of which sold – forced him to take employment as a caller on the stock exchange and as a bank clerk in Cologne, a job he detested. He was dismissed from the bank in August 1923 and returned to Rheydt. During this period he read avidly and was influenced by the works of Oswald Spengler, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Houston Stewart Chamberlain, the British-born German writer whose book The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century (1899) was one of the standard works of the extreme right in Germany. He also began to study the social question and read the works of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Rosa Luxemburg, August Bebel and Gustav Noske. According to German historian Peter Longerich, Goebbels’s diary entries from late 1923 to early 1924 reflected the writings of a man who was isolated, preoccupied with “religious-philosophical” issues and lacked a sense of direction. Diary entries from mid-December 1923 onwards show Goebbels was moving towards the Völkisch nationalist movement.

Goebbels first took an interest in Adolf Hitler and Nazism in 1924. In February 1924, Hitler’s trial for treason began in the wake of his failed attempt to seize power in the Beer Hall Putsch of 8–9 November 1923. The trial attracted widespread press coverage and gave Hitler a platform for propaganda. Hitler was sentenced to five years in prison, but was released on 20 December 1924, after serving just over a year, including pre-trial detention. Goebbels was drawn to the Nazi Party mostly because of Hitler’s charisma and commitment to his beliefs. He joined the Nazi Party around this time, becoming member number 8762. In late 1924, Goebbels offered his services to Karl Kaufmann, who was Gauleiter (Nazi Party district leader) for the Rhine-Ruhr District. Kaufmann put him in touch with Gregor Strasser, a leading Nazi organiser in northern Germany, who hired him to work on their weekly newspaper and undertake secretarial work for the regional party offices. He was also put to work as party speaker and representative for Rhineland–Westphalia.Strasser founded the National Socialist Working Association on 10 September 1925, a short-lived group of about a dozen northern and western German Gauleiter; Goebbels became its business manager and the editor of its biweekly journal, NS-Briefe.[45] Members of Strasser’s northern branch of the Nazi Party, including Goebbels, had a more socialist outlook than the rival Hitler group in Munich. Strasser disagreed with Hitler on many parts of the party platform, and in November 1926 began working on a revision.

Hitler viewed Strasser’s actions as a threat to his authority, and summoned 60 Gauleiters and party leaders, including Goebbels, to a special conference in Bamberg, in Streicher’s Gau of Franconia, where he gave a two-hour speech repudiating Strasser’s new political programme.Hitler was opposed to the socialist leanings of the northern wing, stating it would mean “political bolshevization of Germany.” Further, there would be “no princes, only Germans,” and a legal system with no “Jewish system of exploitation … for plundering of our people.” The future would be secured by acquiring land, not through expropriation of the estates of the former nobility, but through colonising territories to the east. Goebbels was horrified by Hitler’s characterisation of socialism as “a Jewish creation” and his assertion that a Nazi government would not expropriate private property. He wrote in his diary: “I no longer fully believe in Hitler. That’s the terrible thing: my inner support has been taken away.”

After reading Hitler’s book Mein Kampf, Goebbels found himself agreeing with Hitler’s assertion of a “Jewish doctrine of Marxism“. In February 1926, Goebbels gave a speech titled “Bolshevism or National-socialism? Lenin or Hitler?” in which he asserted that communism or Marxism could not save the German people, but he believed it would cause a “socialist nationalist state” to arise in Russia.[51] In 1926, Goebbels published a pamphlet titled Nazi-Sozi which attempted to explain how National Socialism differed from Marxism.

In hopes of winning over the opposition, Hitler arranged meetings in Munich with the three Greater Ruhr Gau leaders, including Goebbels. Goebbels was impressed when Hitler sent his own car to meet them at the railway station. That evening, Hitler and Goebbels both gave speeches at a beer hall rally. The following day, Hitler offered his hand in reconciliation to the three men, encouraging them to put their differences behind them. Goebbels capitulated completely, offering Hitler his total loyalty. He wrote in his diary: “I love him … He has thought through everything,” “Such a sparkling mind can be my leader. I bow to the greater one, the political genius.” He later wrote: “Adolf Hitler, I love you because you are both great and simple at the same time. What one calls a genius.” As a result of the Bamberg and Munich meetings, the National Socialist Working Association was disbanded. Strasser’s new draft of the party programme was discarded, the original National Socialist Program of 1920 was retained unchanged, and Hitler’s position as party leader was greatly strengthened.

At Hitler’s invitation, Goebbels spoke at party meetings in Munich and at the annual Party Congress, held in Weimar in 1926. For the following year’s event, Goebbels was involved in the planning for the first time. He and Hitler arranged for the rally to be filmed. Receiving praise for doing well at these events led Goebbels to shape his political ideas to match Hitler’s, and to admire and idolise him even more.

Goebbels was first offered the position of party Gauleiter for the Berlin section in August 1926. He travelled to Berlin in mid-September and by the middle of October accepted the position. Thus Hitler’s plan to divide and dissolve the northwestern Gauleiters group that Goebbels had served in under Strasser was successful. Hitler gave Goebbels great authority over the area, allowing him to determine the course for organisation and leadership for the Gau. Goebbels was given control over the local Sturmabteilung (SA) and Schutzstaffel (SS) and answered only to Hitler. The party membership numbered about 1,000 when Goebbels arrived, and he reduced it to a core of 600 of the most active and promising members. To raise money, he instituted membership fees and began charging admission to party meetings. Aware of the value of publicity (both positive and negative), he deliberately provoked beer-hall battles and street brawls, including violent attacks on the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Goebbels adapted recent developments in commercial advertising to the political sphere, including the use of catchy slogans and subliminal cues. His new ideas for poster design included using large type, red ink, and cryptic headers that encouraged the reader to examine the fine print to determine the meaning.

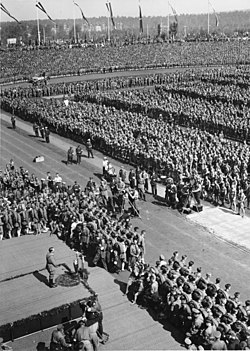

Goebbels speaks at a political rally (1932). This body position, with arms akimbo, was intended to show the speaker as being in a position of authority.

Goebbels giving a speech in Lustgarten, Berlin, August 1934. This hand gesture was used while delivering a warning or threat.

Like Hitler, Goebbels practised his public speaking skills in front of a mirror. Meetings were preceded by ceremonial marches and singing, and the venues were decorated with party banners. His entrance (almost always late) was timed for maximum emotional impact. Goebbels usually meticulously planned his speeches ahead of time, using pre-planned and choreographed inflection and gestures, but he was also able to improvise and adapt his presentation to make a good connection with his audience. He used loudspeakers, decorative flames, uniforms, and marches to attract attention to speeches.

Goebbels’ tactic of using provocation to bring attention to the Nazi Party, along with violence at the public party meetings and demonstrations, led the Berlin police to ban the Nazi Party from the city on 5 May 1927. Violent incidents continued, including young Nazis randomly attacking Jews in the streets. Goebbels was subjected to a public speaking ban until the end of October. During this period, he founded the newspaper Der Angriff (The Attack) as a propaganda vehicle for the Berlin area, where few supported the party. It was a modern-style newspaper with an aggressive tone; 126 libel suits were pending against Goebbels at one point.To his disappointment, circulation was initially only 2,000. Material in the paper was highly anti-communist and antisemitic. Among the paper’s favourite targets was the Jewish Deputy Chief of the Berlin Police Bernhard Weiß. Goebbels gave him the derogatory nickname “Isidore” and subjected him to a relentless campaign of Jew-baiting in the hope of provoking a crackdown he could then exploit. Goebbels continued to try to break into the literary world, with a revised version of his book Michael finally being published, and the unsuccessful production of two of his plays (Der Wanderer and Die Saat (The Seed)). The latter was his final attempt at playwriting.[75] During this period in Berlin he had relationships with many women, including his old flame Anka Stalherm, who was now married and had a small child. He was quick to fall in love, but easily tired of a relationship and moved on to someone new. He worried too about how a committed personal relationship might interfere with his career.

The ban on the Nazi Party was lifted before the Reichstag elections on 20 May 1928. The Nazi Party lost nearly 100,000 voters and earned only 2.6 per cent of the vote nationwide. Results in Berlin were even worse, where they attained only 1.4 per cent of the vote. Goebbels was one of the first 12 Nazi Party members to gain election to the Reichstag. This gave him immunity from prosecution for a long list of outstanding charges, including a three-week jail sentence he received in April for insulting the deputy police chief Weiß. The Reichstag changed the immunity regulations in February 1931, and Goebbels was forced to pay fines for libellous material he had placed in Der Angriff over the course of the previous year. Goebbels continued to be elected to the Reichstag at every subsequent election during the Weimar and Nazi regimes.

In his newspaper Berliner Arbeiterzeitung (Berlin Workers Newspaper), Gregor Strasser was highly critical of Goebbels’ failure to attract the urban vote. However, the party as a whole did much better in rural areas, attracting as much as 18 per cent of the vote in some regions.This was partly because Hitler had publicly stated just prior to the election that Point 17 of the party programme, which mandated the expropriation of land without compensation, would apply only to Jewish speculators and not private landholders.After the election, the party refocused their efforts to try to attract still more votes in the agricultural sector. In May, shortly after the election, Hitler considered appointing Goebbels as party propaganda chief. But he hesitated, as he worried that the removal of Gregor Strasser from the post would lead to a split in the party. Goebbels considered himself well suited to the position, and began to formulate ideas about how propaganda could be used in schools and the media.

By 1930 Berlin was the party’s second-strongest base of support after Munich.That year the violence between the Nazis and communists led to local SA troop leader Horst Wessel being shot by two members of the KPD. He later died in hospital. Exploiting Wessel’s death, Goebbels turned him into a martyr for the Nazi movement. He officially declared Wessel’s march Die Fahne hoch (Raise the flag), renamed as the Horst-Wessel-Lied, to be the Nazi Party anthem.

The Great Depression greatly impacted Germany and by 1930 there was a dramatic increase in unemployment. During this time, the Strasser brothers started publishing a new daily newspaper in Berlin, the Nationaler Sozialist Like their other publications, it conveyed the brothers’ own brand of Nazism, including nationalism, anti-capitalism, social reform, and anti-Westernism. Goebbels complained vehemently about the rival Strasser newspapers to Hitler and admitted that their success was causing his own Berlin newspapers to be “pushed to the wall”. In late April 1930, Hitler publicly and firmly announced his opposition to Gregor Strasser and appointed Goebbels to replace him as Reich leader of Nazi Party propaganda. One of Goebbels’ first acts was to ban the evening edition of the Nationaler Sozialist. Goebbels was also given control of other Nazi papers across the country, including the party’s national newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter (People’s Observer). He still had to wait until 3 July for Otto Strasser and his supporters to announce they were leaving the Nazi Party. Upon receiving the news, Goebbels was relieved the “crisis” with the Strassers was finally over and glad that Otto Strasser had lost all power.

The rapid deterioration of the economy led to the resignation on 27 March 1930 of the coalition government that had been elected in 1928. Paul von Hindenburg appointed Heinrich Brüning as chancellor. A new cabinet was formed, and Hindenburg used his power as president to govern via emergency decrees. Goebbels took charge of the Nazi Party’s national campaign for Reichstag elections called for 14 September 1930. Campaigning was undertaken on a huge scale, with thousands of meetings and speeches held all over the country. Hitler’s speeches focused on blaming the country’s economic woes on the Weimar Republic, particularly its adherence to the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, which required war reparations that had proven devastating to the German economy. He proposed a new German society based on race and national unity. The resulting success took even Hitler and Goebbels by surprise: the party received 6.5 million votes nationwide and took 107 seats in the Reichstag, making it the second-largest party in the country.

In late 1930 Goebbels met Magda Quandt, a divorcée who had joined the party a few months earlier. She worked as a volunteer in the party offices in Berlin, helping Goebbels organise his private papers. Her flat on Reichskanzlerplatz soon became a favourite meeting place for Hitler and other Nazi Party officials. Goebbels and Quandt married on 19 December 1931 at a Protestant church. Hitler was his best man.

At the 24 April 1932 Prussian state election, Goebbels won a seat in the Landtag of Prussia. For the two Reichstag elections held in 1932, Goebbels organised massive campaigns that included rallies, parades, speeches, and Hitler travelling around the country by aeroplane with the slogan “the Führer over Germany”. Goebbels wrote in his diary that the Nazis must gain power and exterminate Marxism.He undertook numerous speaking tours during these election campaigns and had some of their speeches published on gramophone records and as pamphlets. Goebbels was also involved in the production of a small collection of silent films that could be shown at party meetings, though they did not yet have enough equipment to widely use this medium. Many of Goebbels’ campaign posters used violent imagery such as a giant half-clad male destroying political opponents or other perceived enemies such as “International High Finance”. His propaganda characterised the opposition as “November criminals“, “Jewish wire-pullers”, or a communist threat.

Support for the party continued to grow, but neither of these elections led to a majority government. In an effort to stabilise the country and improve economic conditions, Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Reich chancellor on 30 January 1933.

To celebrate Hitler’s appointment as chancellor, Goebbels organised a torchlight parade in Berlin on the night of 30 January of an estimated 60,000 men, many in the uniforms of the SA and SS. The spectacle was covered by a live state radio broadcast, with commentary by longtime party member and future Minister of Aviation Hermann Göring. Goebbels was disappointed not to be given a post in Hitler’s new cabinet. Bernhard Rust was appointed as Minister of Culture, the post that Goebbels was expecting to receive.Like other Nazi Party officials, Goebbels had to deal with Hitler’s leadership style of giving contradictory orders to his subordinates, while placing them into positions where their duties and responsibilities overlapped. In this way, Hitler fostered distrust, competition, and infighting among his subordinates to consolidate and maximise his own power. The Nazi Party took advantage of the Reichstag fire of 27 February 1933, with Hindenburg passing the Reichstag Fire Decree the following day at Hitler’s urging. This was the first of several pieces of legislation that dismantled democracy in Germany and put a totalitarian dictatorship—headed by Hitler—in its place. On 5 March, yet another Reichstag election took place, the last to be held before the defeat of the Nazis at the end of the Second World War. While the Nazi Party increased their number of seats and percentage of the vote, it was not the landslide expected by the party leadership. Goebbels received Hitler’s appointment to the cabinet, becoming head of the newly created Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda in March 1933.

The role of the new ministry, which set up its offices in the 18th-century Ordenspalais across from the Reich Chancellery, was to centralise Nazi control of all aspects of German cultural and intellectual life. On 25 March 1933, Goebbels said that he hoped to increase popular support of the party from the 37 per cent achieved at the last free election held in Germany to 100 per cent support. An unstated goal was to present to other nations the impression that the Nazi Party had the full and enthusiastic backing of the entire population. One of Goebbels’ first productions was staging the Day of Potsdam, a ceremonial passing of power from Hindenburg to Hitler, held in Potsdam on 21 March. He composed the text of Hitler’s decree authorising the Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses, held on 1 April. Later that month, Goebbels travelled back to Rheydt, where he was given a triumphal reception. The townsfolk lined the main street, which had been renamed in his honour. On the following day, Goebbels was declared a local hero.

Goebbels converted the 1 May holiday from a celebration of workers’ rights (observed as such especially by the communists) into a day celebrating the Nazi Party. In place of the usual ad hoc labour celebrations, he organised a huge party rally held at Tempelhof Field in Berlin. The following day, all trade union offices in the country were forcibly disbanded by the SA and SS, and the Nazi-run German Labour Front was created to take their place. “We are the masters of Germany,” he commented in his diary entry of 3 May. Less than two weeks later, he gave a speech at the Nazi book burning in Berlin on 10 May, a ceremony he suggested.

Meanwhile, the Nazi Party began passing laws to marginalise Jews and remove them from German society. The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, passed on 7 April 1933, forced all non-Aryans to retire from the legal profession and civil service.[126] Similar legislation soon deprived Jewish members of other professions of their right to practise.[126] The first Nazi concentration camps (initially created to house political dissenters) were founded shortly after Hitler seized power. In a process termed Gleichschaltung (coordination), the Nazi Party proceeded to rapidly bring all aspects of life under control of the party. All civilian organisations, including agricultural groups, volunteer organisations, and sports clubs, had their leadership replaced with Nazi sympathisers or party members. By June 1933, virtually the only organisations not in the control of the Nazi Party were the army and the churches. On 2 June 1933, Hitler appointed Goebbels a Reichsleiter, the second highest political rank in the Nazi Party. On 3 October 1933, on the formation of the Academy for German Law, Goebbels was made a member and given a seat on its executive committee. In a move to manipulate Germany’s middle class and shape popular opinion, the regime passed on 4 October 1933 the Schriftleitergesetz (Editor’s Law), which became the cornerstone of the Nazi Party’s control of the popular press.Modelled to some extent on the system in Benito Mussolini‘s Fascist Italy, the law defined a Schriftleiter as anyone who wrote, edited, or selected texts and illustrated material for serial publication. Individuals selected for this position were chosen based on experiential, educational, and racial criteria. The law required journalists to “regulate their work in accordance with National Socialism as a philosophy of life and as a conception of government.”[

In 1934, Goebbels published Vom Kaiserhof zur Reichskanzlei (lit. ’From the Kaiserhof to the Reich Chancellery’), his account of Hitler’s seizure of power, which he based on his diary from 1 January 1932 to 1 May 1933. The book sought to glorify both Hitler and the author. It sold around 660,000 copies, making it Goebbels’s best-selling publication during his lifetime. An English translation was published in 1935 under the title My Part in Germany’s Fight.

At the end of June 1934, top officials of the SA and opponents of the regime, including Gregor Strasser, were arrested and killed in a purge later called the Night of Long Knives. Goebbels was present at the arrest of SA leader Ernst Röhm in Munich. On 2 August 1934, President von Hindenburg died. In a radio broadcast, Goebbels announced that the offices of president and chancellor had been combined, and Hitler had been formally named as Führer und Reichskanzler (leader and chancellor).