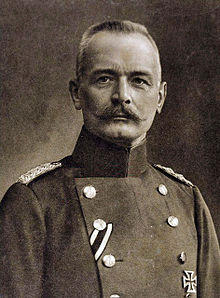

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934), known as simply Paul von Hindenburg, was a German military officer and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War and later became president of Germany from 1925 until his death. He played a key role in the Nazi seizure of power in 1933 when, under pressure from advisers, he appointed Adolf Hitler as chancellor of Germany.

Hindenburg was born to a family of minor Prussian nobility in Posen. Upon completing his education as a cadet, he enlisted in the Third Regiment of Foot Guards as a second lieutenant. He saw combat during the Austro-Prussian and Franco-Prussian wars. In 1873, he was admitted to the prestigious Kriegsakademie in Berlin, where he studied before being appointed to the General Staff Corps. In 1885, he was promoted to major and became a member of the German General Staff. After teaching at the Kriegsakademie, Hindenburg rose to become a lieutenant general by 1900. Around the time of his promotion to General of the Infantry in 1905, Count Alfred von Schlieffen recommended Hindenburg succeed him as Chief of the Great General Staff, but the post went to Helmuth von Moltke in 1906. In 1911, Hindenburg retired.

After World War I began in 1914, Hindenburg was recalled and achieved fame on the Eastern Front as victor of Tannenberg. He oversaw crushing victories against the Russians that made him a national hero and center of a personality cult. By 1916, his popularity had risen to the point he replaced General Erich von Falkenhayn as Chief of the Great General Staff. He and General Erich Ludendorff exploited Emperor Wilhelm II‘s delegation of power to the Supreme Army Command to establish a de facto military dictatorship. Under their leadership, Germany secured Russia’s defeat and achieved the largest advance on the Western Front since the conflict’s outbreak. However, improvements in Germany’s fortunes were reversed, after its Army was decisively defeated in the Second Battle of the Marne and the Allies’ Hundred Days Offensive. Upon the armistice, Hindenburg stepped down as commander-in-chief and retired again in 1919.

In 1925, Hindenburg returned to public life to become the second elected president of the German Weimar Republic. Opposed to Hitler and his Nazi Party, Hindenburg nonetheless played a major role in the instability that resulted in their rise to power. After twice dissolving the Reichstag in 1932, Hindenburg agreed in January 1933 to appoint Hitler as chancellor in coalition with the Deutschnationale Volkspartei. In response to the February 1933 Reichstag fire, Hindenburg approved the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended various civil liberties. He signed the Enabling Act of 1933, which gave the Nazi regime emergency powers. After Hindenburg died the following year, Hitler combined the presidency with the chancellery before declaring himself Führer (lit. ’Leader’) of Germany and transforming the country into a totalitarian state.

Early life

Hindenburg was born in Posen, Prussia, the son of Prussian junker Hans Robert Ludwig von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (1816–1902) and his wife Luise Schwickart (1825–1893), the daughter of physician Karl Ludwig Schwickart and wife Julie Moennich. His paternal grandparents were Otto Ludwig Fady von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (1778–1855), through whom he was remotely descended from the illegitimate daughter of Count Heinrich VI of Waldeck, and his wife Eleonore von Brederfady (d. 1863). Hindenburg’s younger brothers and sister were Otto (b. 1849), Ida (b. 1851) and Bernhard (b. 1859). His family was all Lutheran Protestants in the Evangelical Church of Prussia, which since 1817 included both Calvinist and Lutheran parishioners.

Paul was proud of his family and could trace his ancestors back to 1289. The dual surname was adopted in 1789 to secure an inheritance and appeared in formal documents, but in everyday life, they were von Beneckendorffs. True to family tradition, his father supported his family as an infantry officer; he retired as a major. In the summer, they visited his grandfather at the Hindenburg estate of Neudeck in East Prussia. At age 11, Paul entered the Cadet Corps School at Wahlstatt (now Legnickie Pole, Poland).At 16, he was transferred to the School in Berlin, and, at 18, he served as a page to the widow of King Frederick William IV of Prussia. Graduates entering the army were presented to King William I, who asked for their father’s name and rank. He became a second lieutenant in the Third Regiment of Foot Guards.

In the Prussian Army

Action in two wars

When the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 broke out, Hindenburg wrote to his parents: ‘I rejoice in this bright-coloured future. For the soldier war is the normal state of things[…]If I fall, it is the most honorable and beautiful death.’ During the decisive Battle of Königgrätz, he was briefly knocked unconscious by a bullet that pierced his helmet and creased the top of his skull. Quickly regaining his senses, he wrapped his head in a towel and resumed leading his detachment, winning a decoration. He was a battalion adjutant when the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) broke out. After weeks of marching, the Guards attacked the village of Saint Privat (near Metz). Climbing a gentle slope, they came under heavy fire from the superior French rifles. After four hours the Prussian artillery came up to blast the French lines while the infantry, filled with the “holy lust of battle”, swept through the French lines. His regiment suffered 1096 casualties, and he became a regimental adjutant. The Guards were spectators at the Battle of Sedan and for the following months sat in the siege lines surrounding Paris. He was his regiment’s elected representative at the Palace of Versailles when the German Empire was proclaimed on 18 January 1871; at 1.98m (6 feet 6 inches) tall with a muscular frame and striking blue eyes, he was an impressive figure. After the French surrender, he watched from afar the suppression of the Paris Commune.

General Staff

In 1873, he passed the highly competitive entrance examination for admission to the Kriegsakademie in Berlin. After three years of study, his grades were high enough for an appointment with the General Staff. He was promoted to captain in 1878 and assigned to the staff of the II Corps. He married the intelligent and accomplished Gertrud von Sperling (1860–1921), daughter of General Oskar von Sperling, in 1879. The couple would have two daughters, Irmengard Pauline (1880) and Annemaria (1891), and one son, Oskar (1883). Next, he commanded an infantry company, in which his men were ethnic Poles.

He was transferred in 1885 to the General Staff and was promoted to major. His section was led by Count Alfred von Schlieffen, a student of encirclement battles like Cannae, whose Schlieffen Plan proposed to pocket the French Army. For five years Hindenburg also taught tactics at the Kriegsakademie. At the maneuvers of 1885, he met the future Kaiser Wilhelm II; they met again at the next year’s war game in which Hindenburg commanded the “Russian army“. He learned the topography of the lakes and sand barrens of East Prussia during the annual Great General Staff’s ride in 1888. The following year, he moved to the War Ministry, to write the field service regulations on field-engineering and on the use of heavy artillery in field engagements; both were used during the First World War. He became a lieutenant colonel in 1891, and, two years later, was promoted to colonel, commanding an infantry regiment. He became chief of staff of the VIII Corps in 1896.

Field commands and retirement

Hindenburg became a major-general (equivalent to a British and US brigadier general) in 1897, and in 1900 he was promoted to lieutenant general (equivalent to major-general) and received command of the 28th Infantry Division. Five years later he was made commander of the IV Corps based in Magdeburg as a General of the Infantry (lieutenant-general; the German equivalent to four-star rank was Colonel-General). The annual maneuvers taught him how to maneuver a large force; in 1908 he defeated a corps commanded by the Kaiser.Schlieffen recommended him as Chief of the General Staff in 1909, but he lost out to Helmuth von Moltke. He retired in 1911 “to make way for younger men”. He had been in the army for 46 years, including 14 years in General Staff positions. During his career, Hindenburg did not have political ambitions and remained a staunch monarchist.

World War I

1914

Assumption of command in East Prussia

When WWI broke out, Hindenburg was retired in Hannover. On 22 August, due to the purge of German command following Russian success in East Prussia, he was selected by the War Cabinet and the German Supreme Army Command (Oberste Heeresleitung, OHL) to assume command of the German Eighth Army in East Prussia, with General Erich Ludendorff as his chief of staff. After the Eighth Army had been defeated by the Russian 1st Army at Gumbinnen, it had found itself in danger of encirclement as the Russian 2nd Army under General Alexander Samsonov advanced from the south towards the Vistula River. Momentarily panicked, Eighth Army commander Maximilian von Prittwitz notified OHL of his intent to withdraw his forces into Western Prussia. The Chief of the German General Staff, Generaloberst Helmuth von Moltke, responded by relieving Prittwitz and replacing him with Hindenburg.

Tannenberg

Upon arriving at Marienburg on 23 August, Hindenburg and Ludendorff were met by members of the 8th Army’s staff led by Lieutenant Colonel Max Hoffmann, an expert on the Russian army. Hoffman informed them of his plans to shift part of the 8th Army south to attack the exposed left flank of the advancing Russian Second Army. Agreeing with Hoffman’s strategy, Hindenburg authorized Ludendorff to transfer most of the 8th Army south while leaving only two cavalry brigades to face the Russian First Army in the north. In Hindenburg’s words the line of soldiers defending Germany’s border was “thin, but not weak”, because the men were defending their homes. If pushed too hard by the Second Army, he believed they would cede ground only gradually as German reinforcements continued to mass on the invading Russians’ flanks before ultimately encircling and annihilating them. On the eve of the ensuing battle, Hindenburg reportedly strolled close to the decaying walls of the fortress of the Knights of Prussia, recalling how the Knights of Prussia were defeated by the Slavs in 1410 at nearby Tannenberg.

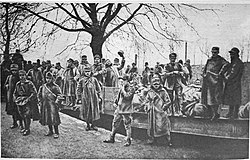

On the night of 25 August, Hindenburg told his staff, “Gentlemen, our preparations are so well in hand that we can sleep soundly tonight”. On the day of the battle, Hindenburg reportedly watched from a hilltop as his forces’ weak center gradually gave ground until the sudden roar of German guns to his right heralded the surprise attack on the Russians’ flanks. Ultimately, the Battle of Tannenberg resulted in the destruction of the Russian 2nd Army, with 92,000 Russians captured together with four hundred guns, while German casualties numbered only 14,000. According to British field marshal Edmund Ironside it was the “greatest defeat suffered by any of the combatants during the war”. Recognizing the victory’s propaganda value, Hindenburg suggested naming the battle “Tannenberg” as a way of “avenging” the defeat inflicted on the Order of the Teutonic Knights by the Polish and Lithuanian knights in 1410, even though it was fought nowhere near the field of Tannenberg.

After this decisive victory, Hindenburg re-positioned the Eighth Army to face the Russian First Army. Hindenburg’s tactics spurned head-on attacks all along the front in favor of schwerpunkte: sharp, localized hammer blows. Two schwerpunkte struck in the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes. Two columns drove east from these breakthrough points to pocket the Russians led by General Paul von Rennenkampf, who managed to retreat 100 km (62 mi) with heavy losses. In the first six weeks of the war the Russians had lost more than 310,000 men. Eight hundred thousand refugees were able to return to their East Prussian homes, thanks to victories that strikingly contrasted with the bloody deadlock of the Western Front following the failure of the Schlieffen Plan.

Partnership with Ludendorff

The Hindenburg-Ludendorff duo’s successful performance on the Eastern Front in 1914 marked the beginning of a military and political partnership that lasted until the end of the war. As Hindenburg wrote to the Kaiser a few months later: “[Ludendorff] has become my faithful adviser and a friend who has my complete confidence and cannot be replaced by anyone.” Despite their strikingly dissimilar temperaments, the older general’s calm decisiveness proved to be an outstanding fit for Ludendorff’s energy and tactical ingenuity. Ludendorff’s nerves twice drove him to consider changing their plans for Tannenberg at the last minute; both times Hindenburg talked to him privately and his confidence wavered no further.

Defending Silesia

On the east bank of the Vistula in Poland the Russians were mobilizing new armies which were shielded from attack by the river; once assembled they would cross the river to march west into Silesia. To counter the Russians’ pending invasion of Silesia, Hindenburg advanced into Poland and occupied the west bank of the Vistula opposite from where Russian forces were mobilizing. He set up headquarters at Posen in West Prussia, accompanied by Ludendorff and Hoffmann.When the Russians attempted to cross the Vistula, the German forces under his command held firm, but the Russians were able to cross into the Austro-Hungarian sector to the south. Hindenburg retreated and destroyed all railways and bridges so that the Russians would be unable to advance beyond 120 km (75 mi) west of their railheads—well short of the German frontier.

On 1 November 1914 Hindenburg was appointed Ober Ost (commander in the east) and was promoted to field marshal. To meet the Russians’ renewed push into Silesia, Hindenburg moved the Ninth Army by rail north to Thorn and reinforced it with two corps from the Eighth Army. On 11 November, in a raging snowstorm, his forces surprised the Russian flank in the fierce Battle of Łódź, which ended the immediate Russian threat to Silesia and also captured Poland’s second largest city.

1915

Disagreements with Falkenhayn

Hindenburg argued that the still miserably equipped Russians—some only carried spears—in the huge Polish salient were in a trap in which they could be snared in a cauldron by a southward pincer from East Prussia and a northward pincer from Galicia, using motor vehicles for speed, even though the Russians outnumbered the Germans by three to one. From Hindenburg’s point of view, such an overwhelming triumph could end the war in the Eastern Front. Erich von Falkenhayn, the Chief of Germany’s Great General Staff, rejected his plan as a pipe dream. Nevertheless, urged on by Ludendorff and Hoffman, Hindenburg spent the winter fighting for his strategy by badgering the Kaiser while his press officer recruited notables like the Kaiserin and the Crown Prince to “stab the Kaiser in the back”. The Kaiser compromised by keeping Falkenhayn in supreme command but replacing him as Prussian war minister. In retaliation, Falkenhayn reassigned some of Hindenburg’s forces to a new army group under Prince Leopold of Bavaria and transferred Ludendorff to a new joint German and Austro-Hungarian Southern Army. Hindenburg and Ludendorff reacted by threatening to resign thereby resulting in Ludendorff’s reinstatement under Hindenburg’s command.

Counterattacks in East Prussia and Poland

Following his return, Ludendorff provided Hindenburg with a depressing evaluation of their allies’ army, which already had lost many of their professional officers[33] and had been driven out of much of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, their part of what once had been Poland. Meanwhile, the Russians were inexorably pushing from Galicia toward Hungary through the Carpathian passes. Under orders from Falkenhayn to contain the resurgent Russians, Hindenburg mounted an unsuccessful attack in Poland with his Ninth Army as well as an offensive by the newly formed Tenth Army which made only local gains. Following these setbacks, he set up temporary headquarters at Insterburg, and made plans to eliminate the Russians’ remaining toehold in East Prussia by ensnaring them in a pincer movement between the Tenth Army in the north and Eighth Army in the south. The attack was launched on 7 February. Hindenburg’s forces encircled an entire corps and captured more than 100,000 men in the Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes.

Shortly thereafter, Hindenburg and Ludendorff played a key role in the Central Powers’ Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive. After the Austro-Hungarian fortress of Przemyśl fell on 23 March, Austria-Hungary’s high command pushed for a joint strike on the Russian right flank that could potentially drive their forces out of the Carpathians. Agreeing to the proposal, Falkenhayn moved OHL east to the castle of Pless while forming Army Group von Mackensen from a new German Eleventh Army and the Austro-Hungarian Fourth Army. As Field Marshal August von Mackensen broke through Russian lines between Gorlice and Tarnów, Hindenburg’s Ninth and Tenth Army launched diversionary attacks that threatened Riga in the north. In one of the war’s most successful cavalry actions, three cavalry divisions swept east into Courland, the barren, sandy region near the Baltic coast. The cavalry’s gains were held by Hindenburg’s new Nieman army, named after the river.

In June, the Supreme Army Command ordered Hindenburg to launch a Bug-Narew Offensive in Poland toward the Narew River north of Warsaw. Hindenburg created Army Group Gallwitz, named after its commander. Von Gallwitz was one of many able commanders selected by Hindenburg, who stayed at the new army’s headquarters to be available if needed. (When Berlin approved the new army group, it became Twelfth Army.) The army group broke through the Russian lines after a brief, but intense, bombardment directed by Lieutenant Colonel Georg Bruchmüller, an artillery genius recalled from medical retirement. One-third of the opposing Russian First Army were casualties in the first five hours. From then on Hindenburg often called on Bruchmüller. The Russians withdrew across the Narev River. However, steamroller frontal attacks cost dearly: by 20 August Gallwitz had lost 60,000 men.

Evacuation of Poland

As the Russians withdrew from the Polish Salient, Falkenhayn insisted on pursuing them into Lithuania. However, Hindenburg and Ludendorff were dissatisfied with this plan. Hindenburg would later claim that he saw it as “a pursuit in which the pursuer gets more exhausted than the pursued”.

On 1 June, Hindenburg’s Nieman and Tenth Armies spearheaded attacks into Courland in an attempt to pocket the defenders. Ultimately, this plan was foiled by the prudent commander of the Fifth Russian Army who defied orders by withdrawing into defensible positions shielding Riga.

Despite the setback in Latvia, Hindenburg, and Ludendorff continued to rack up victories on the Eastern Front. In August, the Germans stormed the Novogeorgievsk fortress. Numerous Russian sources call the fall of Novogeorgievsk the most shameful page in the history of the Russian Imperial army. The German Tenth Army besieged Kovno, a Lithuanian city on the Nieman River defended by a circle of forts. It fell on 17 August, along with 1,300 guns and almost 1 million shells. On 5 August his forces were consolidated into Army Group Hindenburg, which took the city of Grodno after bitter street fighting but could not trap the retreating defenders because the rail lines lacked the capacity to bring up the needed men. They occupied Vilnius on 18 September, then halted on ground favorable for a defensive line. On 6 August, German troops under Hindenburg used chlorine gas against Russian troops defending Osowiec Fortress. The Russians demolished much of Osowiec and withdrew on 18 August.

In October, Hindenburg moved headquarters to Kovno. They were responsible for 108,800 km2 (42,000 mi2) of conquered Russian territory, which was home to three million people and became known as Ober Ost. The troops built fortifications on the eastern border while Ludendorff “with his ruthless energy” headed the civil government, using forced labor to repair the war damages and to dispatch useful products, like hogs, to Germany. A Hindenburg son-in-law, who was a reserve officer and a legal expert, joined the staff to write a new legal code. Baltic Germans who owned vast estates feted Hindenburg and he hunted their game preserves.

Hindenburg would later judge German operations in 1915 to be “unsatisfactory”. In his memoirs, he recounted that “[t]he Russian bear had escaped our clutches” and abandoning the Polish salient had shortened their lines substantially. Conversely, victorious Falkenhayn believed that “The Russian Army has been so weakened by the blows it has suffered that Russia need not be seriously considered a danger in the foreseeable future”. The Russians replaced their experienced supreme commander, Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, a man whose skill Hindenburg held in high regard, with the Tsar.

1916

Brusilov Offensive

Main article: Brusilov Offensive

In the spring of 1916, the Central Powers experienced a military catastrophe in the East that left Germany bearing much of the war effort until the end of hostilities. On 4 June, the Russian Army began a massive offensive along 480 km (300 mi) of the southwestern front in present-day western Ukraine. In the ensuing onslaught, four armies commanded by General Aleksei Brusilov overwhelmed entrenchments that the Austro-Hungarians long regarded as impregnable. Probing assault troops located three weak spots which then were struck in force. In nine days they captured more than 200,000 men and 200 guns and pushed into the open country.

Under Hindenburg’s command, Ober Ost desperately shored up weak points with soldiers stripped from less threatened positions. Ludendorff was so distraught on the phone to OHL that General Wilhelm Groener (who directed the army’s railroads and had been a competitor with Ludendorff on the General Staff) was sent to evaluate his nerves, which were judged satisfactory. For a week the Russians kept attacking: they lost 80,000 men; the defenders 16,000. On 16 July the Russians attacked the German lines west of Riga but were ultimately thwarted. When looking back on the Russian offensive, Hindenburg admitted that another attack of such scale and ferocity would have left his forces “faced with the menace of a complete collapse.”

Commander of the Eastern Front

After having their strength decimated by the Russians in the Brusilov Offensive, the Austro-Hungarian forces submitted their Eastern Front forces to Hindenburg’s command on 27 July (except for Archduke Karl’s Army Group in southeast Galicia, in which General Hans von Seeckt was chief of staff). General von Eichhorn took over Army Group Hindenburg, while Hindenburg and Ludendorff, on a staff train equipped with the most advanced communication apparatus, visited their new forces. At threatened points, they formed mixed German and Austro-Hungarian units while other Austro-Hungarian formations were bolstered by a sprinkling of German officers. Officers were exchanged between the German and Austro-Hungarian armies for training. The derelict citadel of the Brest Fortress was refurbished as their headquarters. Their front was almost 1,000 km (620 mi) and their only reserves were a cavalry brigade plus some artillery and machine gunners.

Supreme Commander of the Central Powers

In the west, the Germans were hemorrhaging in the battles of Verdun and the Somme. Influential Army officers, led by the artillery expert Lieutenant Colonel Max Bauer, a friend of Ludendorff’s, lobbied against Falkenhayn, deploring his futile steamroller at Verdun and his inflexible defense along the Somme, where he packed troops into the front-line to be battered by the hail of shells and sacked commanders who lost their front-line trench. German leaders contrasted Falkenhayn’s bludgeon with Hindenburg’s deft parrying. The tipping point came when Falkenhayn ordered a spoiling attack by Bulgaria on Entente lines in Macedonia, which failed with heavy losses. Thus emboldened, Romania declared war on Austro-Hungary on 27 August, adding 650,000 trained enemies who invaded Hungarian Transylvania. Falkenhayn had been adamant that Romania would remain neutral. During the Kaiser’s deliberations about who should command Falkenhayn said “Well, if the Herr Field Marshall has the desire and the courage to take the post”. Hindenburg replied “The desire, no, but the courage—yes”. Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg favored Hindenburg, supposing him amenable to moderate peace terms, mistaking his amiability as tractability and unaware that he was intent on enlarging Prussia.[citation needed]

Hindenburg was summoned to Pless on 29 August where he was named Chief of the Great General Staff and, by extension, the Supreme Army Command. Ludendorff demanded joint responsibility for all decisions”;Hindenburg did not demur. Henceforth, Ludendorff was entrusted with signing most orders, directives, and daily press reports. The eastern front was commanded by Leopold of Bavaria, with Hoffmann as his chief of staff. Hindenburg was also appointed the Supreme War Commander of the Central Powers, with nominal control over six million men. Until the end of the war, this arrangement formed the basis of Hindenburg’s leadership which would come to be known as the Third OHL.

The British were unimpressed: General Charteris, Haig’s intelligence chief, wrote to his wife “poor old Hindenburg is sixty-four years of age, and will not do very much.” Conversely, the German War Cabinet was impressed by his swift decision-making. They credited “Old Man Hindenburg” with ending the “Verdun folly” and setting in motion the “brilliant” conquest of Romania.

Hindenburg and Ludendorff visited the Western Front in September, meeting the Army commanders and their staffs as well as their leaders: Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, Albrecht, Duke of Württemberg and Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia. Both crown princes, with Prussian chiefs of staff, commanded Army Groups. Rupprecht and Albrecht were presented with field marshal’s batons. Hindenburg told them that they must stand on the defensive until Romania was dealt with, meanwhile defensive tactics must be improved—ideas were welcome. A backup defensive line, which the Entente called the Hindenburg Line, would be constructed immediately. Ludendorff promised more arms. Rupprecht was delighted that two such competent men had “replaced the dilettante ‘Falkenhayn’.” Bauer was impressed that Hindenburg “saw everything only with the eye of the soldier.”

Bolstering defense

Under Field Marshal Hindenburg’s leadership, the German Supreme Army Command issued a Textbook of Defensive Warfare that recommended fewer defenders in the front line relying on light machine guns. If pushed too hard, they were permitted to pull back. Front-line defenses were organized so that penetrating enemy forces found themselves cut down by machine gun fire and artillery from those who knew the ranges and location of their own strong points. Subsequently, the infantry would counterattack while the attacker’s artillery was blind because they were unsure where their own men were. A reserve division was positioned immediately behind the line, if it entered the battle it was commanded by the division whose position had been penetrated. (Mobile defense was also used in World War II.) Responsibilities were reassigned to implement the new tactics: front-line commanders took over reserves ordered into the battle and for flexibility, infantry platoons were subdivided into eight-man units under a noncom.

Field officers who visited headquarters often were invited to speak with Hindenburg, who inquired about their problems and recommendations. At this time he was especially curious about the eight-man units, which he regarded as “the greatest evidence of the confidence which we placed in the moral and mental powers of our army, down to its smallest unit.” Revised Infantry Field Regulations were published and taught to all ranks, including at a school for division commanders, where they maneuvered a practice division. A monthly periodical informed artillery officers about new developments. In the last months of 1916, the British battering along the Somme produced fewer German casualties. Overall, “In a fierce and obstinate conflict on the Somme, which lasted five months, the enemy pressed us back to a depth of about six miles on a stretch of nearly twenty-five miles Thirteen new divisions were created by reducing the number of men in infantry battalions, and divisions now had an artillery commander. Every regiment on the western front created an assault unit of stormtroopers selected from their fittest and most aggressive men. Lieutenant General Ernst von Höppner was given responsibility for both aerial and antiaircraft forces; the army’s vulnerable zeppelins went to the navy. Most cavalry regiments were dismounted and the artillery received their badly needed horses.

In October General Philippe Pétain began a series of limited attacks at Verdun, each starting with an intense bombardment coordinated by his artillery commander General Robert Nivelle. Then a double creeping barrage led the infantry into the shattered first German lines, where the attackers stopped to repel counterattacks. With repeated nibbles by mid-December 1916 the French retook all the ground the Germans had paid for so dearly. Nivelle was given command of the French Army.

Headquarters routine

Hindenburg’s day at OHL began at 09:00 when he and Ludendorff discussed the reports—usually quickly agreeing on what was to be done. Ludendorff would give their staff of about 40 officers their assignments, while Hindenburg walked for an hour or so, thinking or chatting with guests. After conferring again with Ludendorff, he heard reports from his departmental heads, met with visitors, and worked on correspondence. At noon Ludendorff gave the situation report to the Kaiser unless an important decision was required when Hindenburg took over. He lunched with his personal staff, which included a son-in-law who was an Army officer. Dinner at 20:00 was with the general staff officers of all ranks and guests—crowned heads, allied leaders, politicians, industrialists and scientists. They left the table to subdivide into informal chatting groups. At 21:30 Ludendorff announced that time was up and they returned to work. After a junior officer summarized the daily reports, he might confer with Ludendorff again before retiring.

The Hindenburg program

Under Hindenburg, the Third OHL set ambitious benchmarks for arms production in what became known as the Hindenburg Programme, which was directed from the War Office by General Groener. Major goals included a new light machine gun, updated artillery, and motor transport, but no tanks because they considered them too vulnerable to artillery. To increase output they needed skilled workers. The army released a million men.For total war, the Supreme Army Command wanted all German men and women from 15 to 60 enrolled for national service. Hindenburg also wanted the universities closed, except for medical training, so that empty places would not be filled by women. To swell the next generation of soldiers he wanted contraceptives banned and bachelors taxed.When a Polish army was being formed he wanted Jews excluded. Few of these ideas were adopted, because their political maneuvering was vigorous but inept, as Admiral Müller of the Military Cabinet observed “Old Hindenburg, like Ludendorff, is no politician, and the latter is at the same time a hothead.” For example, women were not included in the service law that ultimately passed, because in fact more women were already seeking employment than there were openings.

The extent of his command

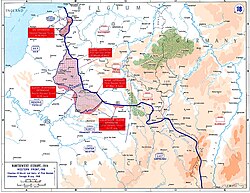

Following the death of Austro-Hungarian emperor Franz Joseph on 21 November, Hindenburg met his successor Charles, who was frank about hoping to stop the fighting. Hindenburg’s Eastern Front ran south from the Baltic to the Black Sea through what now are the Baltic States, Ukraine, and Romania. In Italy, the line ran from the Swiss border on the west to the Adriatic east of Venice. The Macedonian front extended along the Greek border from the Adriatic to the Aegean. The line contested by the Russians and Ottomans between the Black and Caspian Sea ran along the heights of the Caucasus mountains. Hindenburg urged the Ottomans to pull their men off the heights before winter but they did not. In his memoirs, he would later allege this was because of their “policy of massacre of the Armenians“. The front in Palestine ran from the Mediterranean to the southern end of the Dead Sea, and the defenders of Baghdad had a flank on the Tigris River. The Western Front ran southward from Belgium until near Laon, where it turned east to pass Verdun before again turning south to end at the Swiss Border. The remaining German enclaves in Africa were beyond his reach; an attempt to resupply them by dirigible failed. The Central Powers were surrounded and outnumbered.

1917

Arms buildup and unrestricted submarine warfare

By the second quarter of 1917, Hindenburg and Ludendorff were able to assemble 680,000 more men in 53 new divisions[70] and provide them with an adequate supply of new light machine guns. Field guns were increased from 5,300 to 6,700 and heavies from 3,700 to 4,340. They tried to foster fighting spirit by “patriotic instruction” with lectures and films[71] to “ensure that a fight is kept up against all agitators, croakers and weaklings”.[72] Meanwhile, to mitigate the risk of being attacked before their buildup was complete, Germany’s new military leadership waged unrestricted submarine warfare on allied shipping, which they claimed would defeat the British in six months. Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg and his allies expressed opposition to this policy, not wanting to bring the United States and other neutrals into the war. After securing the Dutch and Danish borders, Hindenburg announced that unrestricted submarine warfare was imperative and Ludendorff added his voice. On 9 January the chancellor was forced to bow to their unsound military judgments.[citation needed]

OHL moved west to the pleasant spa town of Bad Kreuznach in southwest Germany, which was on a main rail line. The Kaiser’s quarters were in the spa building, staff offices were in the orange court, and the others lived in the hotel buildings. In February a third Army Group was formed on the Western Front to cover the front in Alsace-Lorraine, commanded by Archduke Albrecht of Württemberg. Some effective divisions from the east were exchanged for less competent divisions from the west. Since their disasters of the previous year, the Russian infantry had shown no fight and in March the revolution erupted in Russia. Shunning opportunity, the Central Powers stayed put; Hindenburg feared that invaders would resurrect the heroic resistance of 1812.[citation needed]

The great withdrawal and defending the Western Front

[edit]

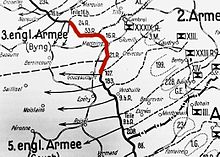

On the Western Front, the Third OHL deduced the German Army’s huge salient between the valley of the Somme and Laon obviously was vulnerable to a pincer attack, which indeed the French were planning. The new Hindenburg line ran across its base. Subsequently, On 16 March, Hindenburg authorized Operation Alberich whereby German forces were ordered to move out all able-bodied inhabitants and portable possessions to this line. In the process, they destroyed every building, leveled all roads and bridges, cut down every tree, fouled every well, and burned every combustible. In 39 days the Germans withdrew from a 1000 mi2 (2,590 km2) area, more ground than they had lost to all Allied offensives since 1914.[73] The cautiously following Allies also had to cope with booby traps, some exploding a month later. The new German front called the Hindenburg line was 42 km (26 mi) shorter freeing-up 14 German divisions.[citation needed]

On 9 April, the British attacked at Arras and overtook two German lines while occupying part of a third as the Canadians swept the Germans completely off the Vimy Ridge. When the excitable Ludendorff became distraught over such developments, Hindenburg reportedly calmed his First Quartermaster-General by “pressing his hand” and assuring him, “We have lived through more critical times than today together.“[74] Ultimately, the British tried to exploit their opening with a futile cavalry charge but did not press further. In the battle’s aftermath, the Third OHL discovered one reason behind the British attack’s success was that the Sixth Army commander, Ludwig von Falkenhausen, had failed to properly apply their instructions for a defense in depth by keeping reserve troops too far back from the front lines.[75][76] As a result of this failure, Falkenhausen along with several staff officers were stripped of their command.[77]

The Eastern Front

[edit]

After the Romanov dynasty’s fall from power, Russia remained at war under the new revolutionary government led by Alexander Kerensky. In the Kerensky Offensive launched on 1 July, the Russian army pushed Austro-Hungarian forces in Galicia on 1 July. In order to counter this success, six German divisions mounted a counterattack on 18 July that tore a hole through the Russian front through which they sliced southward toward Tarnopol. The ensuing German advance threatened to encircle the Russian attackers, thereby causing them to retreat. At the end of August, the advancing Central Powers stopped at the frontier of Moldavia. To keep up the pressure and to seize ground he intended to keep, Hindenburg shifted north to the heavily fortified city of Riga (today in Latvia) which has the broad Dvina River as a moat. On 1 September the Eighth Army, led by Oskar von Hutier, attacked; Bruchmüller’s bombardment, which included gas and smoke shells, drove the defenders from the far bank east of the city, the Germans crossed in barges and then bridged the river, immediately pressing forward to the Baltic coast, pocketing the defenders of the Riga salient. Next, a joint operation with the navy seized Oesel and two smaller islands in the Gulf of Riga. The Bolshevik revolution took Russia out of the war, and an armistice was signed on 16 December.

The Reichstag peace resolution

Hindenburg detested Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg for arguing against unrestricted submarine warfare. Then in July, the Reichstag debated a resolution for peace without “annexations or indemnities”. Colonel Bauer and the Crown Prince hurried to Berlin to block the move. The Minister of War urged Hindenburg and Ludendorff to join them, but when they arrived the Kaiser told them that “there could be no justification for their presence in Berlin”. They should “return in haste to Headquarters where they certainly would be much better occupied.”In a letter to the Emperor dated 12 July 1917, Ludendorff threatened to resign, and Hindenburg joined in the ultimatum. The Kaiser declined to accept. By then the majority parties in the Reichstag saw Bethmann Hollweg as an unacceptable negotiator for peace because he had been chancellor too long and was too weak in his dealings with the Supreme Army Command. The crisis was resolved when Bethmann Hollweg voluntarily resigned. Ludendorff and Bauer wanted to replace both the Kaiser and chancellor with a dictator, but Hindenburg would not agree. On 19 July, the Reichstag passed the resolution calling for a peace of understanding without “territorial acquisitions achieved by force and violations of political, economic or financial integrity”, which the new chancellor Georg Michaelis agreed to “interpret”.

The resolution became advantageous in August when Pope Benedict XV called for peace. The German response cited the resolution to finesse specific questions like those about the future of Belgium. The industrialists opposed Groener’s advocacy of an excess profits tax and insistence that workers take a part in company management. Ludendorff relieved Groener by telegram and sent him off to command a division.[citation needed]

Hindenburg’s 70th birthday was celebrated lavishly all over Germany, 2 October was a public holiday, an honor that until then had been reserved only for the Kaiser. Hindenburg published a birthday manifesto, which ended with the words:

With God’s help our German strength has withstood the tremendous attack of our enemies, because we were one, because each gave his all gladly. So it must stay to the end. ‘Now thank we all our God’ on the bloody battlefield! Take no thought for what is to be after the war! This only brings despondency into our ranks and strengthens the hopes of the enemy. Trust that Germany will achieve what she needs to stand there safe for all time, trust that the German oak will be given air and light for its free growth. Muscles tensed, nerves steeled, eyes front! We see before us the aim: Germany honored, free, and great! God will be with us to the end!”

Victory in Italy

Bavarian mountain warfare expert von Dellmensingen was sent to assess the Austro-Hungarian defenses in Italy, which he found poor. Then he scouted for a site from which an attack could be mounted against the Italians. Hindenburg created a new Fourteenth Army with ten Austro-Hungarian and seven German divisions and enough airplanes to control the air, commanded by Otto von Below. The attackers slipped undetected into the mountains opposite to the opening of the Soča valley. The attack began during the night when the defender’s trenches in the valley were abruptly shrouded in a dense cloud of poison gas released from 894 canisters fired simultaneously from simple mortars. The defenders fled before their masks would fail. The artillery opened fire several hours later, hitting the Italian reinforcements hastening up to fill the gap. The attackers swept over the almost empty defenses and marched through the pass, while mountain troops cleared the heights on either side. The Italians fled west, too fast to be cut off. Entente divisions were rushed to Italy to stem the retreat by holding a line on the Piave River. Below’s Army was dissolved and the German divisions returned to the Western Front, where in October Pétain had directed a successful limited objective attack in which six days of carefully planned bombardment left crater-free pathways for 68 tanks to lead the infantry forward on the Lassaux plateau south of Laon, which forced the Germans off of the entire ridge—the French Army had recovered.

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

In the negotiations with Soviet Russia, Hindenburg wanted to retain control of all Russian territory that the Central Powers occupied, with German grand dukes ruling Courland and Lithuania, as well as a large slice of Poland. Their Polish plan was opposed by Foreign Minister Richard von Kühlmann, who encouraged the Kaiser to listen to the views of Max Hoffmann, chief of staff on the Eastern Front. Hoffmann demurred but when ordered argued that it would be a mistake to bring so many Slavs into Germany, when only a small slice of Poland was needed to improve defenses. Ludendorff was outraged that the Kaiser had consulted a subordinate, while Hindenburg complained that the Kaiser “disregards our opinion in a matter of vital importance.” The Kaiser backed off, but would not approve Ludendorff’s order removing Hoffmann, who is not even mentioned in Hindenburg’s memoir. When the Soviets refused the terms offered at Brest-Litovsk the Germans repudiated the armistice and in a week occupied the Baltic states, Belarus and Ukraine, which had signed the treaty as a separate entity. Now the Russians signed also. Hindenburg helped to force Kühlmann out in July 1918.[citation needed]

1918

In January more than half a million workers went on strike; among their demands was a peace without annexations. The strike collapsed when its leaders were arrested, the labor press suppressed, strikers in the reserve called for active duty, and seven great industrial concern taken under military control, which put their workers under martial law. On 16 January Hindenburg demanded the replacement of Count von Valentini, the chief of the Civil Cabinet. The Kaiser bridled, responding “I do not need your parental advice”, but nonetheless fired his old friend. The Germans were unable to tender a plausible peace offer because OHL insisted on controlling Belgium and retaining the French coalfields. All of the Central Powers’ cities were on the brink of starvation and their armies were on short rations. Hindenburg realized that “empty stomachs prejudiced all higher impulses and tended to make men indifferent.” He blamed his allies’ hunger on poor organization and transportation, not realizing that the Germans would have enough to eat if they collected their harvest efficiently and rationed its distribution effectively.

Opting for a decision in the west

German troops were in Finland, the Baltics, Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, much of Romania, the Crimea, and in a salient east of Ukraine extending east almost to the Volga and south into Georgia and Armenia. Hundreds of thousands of men were needed to hold and police these conquests. More Germans were in Macedonia and in Palestine, where the British were driving north; Falkenhayn was replaced by Otto Liman von Sanders, who had led the defense of Gallipoli. All Hindenburg required was that these fronts stand firm while the Germans won in the west, where now they outnumbered their opponents. He firmly believed that his opponents could be crushed by battlefield defeats regardless of their far superior resources.

Offensive tactics were tailored to the defense. Their opponents were adopting defense in depth. He would attack the British because they were less skillful than the French. The crucial blow would be in Flanders, along the River Lys, where the line was held by the Portuguese Army. However, winter mud prevented action there until April. Consequently, their first attack, named Michael, was on the southern part of the British line, at a projecting British salient near Saint-Quentin. Schwerpunkts would hit on either side of the salient’s apex to pocket its defenders, the V Corps, as an overwhelming display of German power.

Additional troops and skilled commanders, like von Hutier, were shifted from the east. Army Group von Gallwitz was formed in the west on 1 February. One quarter of the western divisions were designated for attack; to counter the elastic defense, during the winter each of them attended a four-week course on infiltration tactics. Storm troops would slip through weak points in the front line and slice through the battle zone, bypassing strong points that would be mopped up by the mortars, flamethrowers, and manhandled field guns of the next wave. As always surprise was essential, so the artillery was slipped into attack positions at night, relying on camouflage for concealment; the British aerial photographers were allowed free rein before D-day. There would be no preliminary registration fire; the gunners were trained for map firing in schools established by Bruchmüller. In the short, intense bombardment each gun fired in a precise sequence, shifting back and forth between different targets, using many gas shells to keep defenders immersed in a toxic cloud. On D-day, the air force would establish air supremacy and strafe enemy strong points, and also update commanders on how far the attackers had penetrated. Signal lamps were used for messaging on the ground. Headquarters moved close to the front and as soon as possible would advance to pre-selected positions in newly occupied ground. OHL moved to Spa, Belgium while Hindenburg and Ludendorff were closer to the attack at Avesnes, France, which re-awoke his memories of occupied France 41 years before.

Breaking the trench stalemate

Operation Michael began on 21 March. The first day’s reports were inconclusive, but by day two the Germans knew they had broken through some of the enemy artillery lines. But the encirclement failed because British stoutness gave their V Corps time to slip out of the targeted salient. On day four, German forces moved on into the open country, and the Kaiser prematurely celebrated by awarding Hindenburg the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross, a medal first created for von Blücher. As usual, Hindenburg set objectives as the situation evolved. South of the salient, the Germans had almost destroyed the British Fifth Army, so they pushed west to cut between the French and British armies. However, they advanced too slowly through the broken terrain of the former Somme battlefields and the ground devastated when withdrawing the year before, and because troops stopped to loot food and clothing, and the Allies maintained a fluid defensive line, manned by troops brought up and supplied by rail and motor transport. Hindenburg hoped the Germans would get close enough to Amiens to bombard the railways with heavy artillery, but they were stopped just short, after having advanced a maximum of 65 km (40 mi). Hindenburg also hoped that civilian morale would crumble, because Paris was being shelled by naval guns mounted on rail carriages 120 km (75 mi) away, but he underestimated French resilience.

The Allied command was dismayed. French headquarters realized: “This much became clear from the terrible adventure, that our enemies were masters of a new method of warfare. … What was even more serious was that it was perceived that the enemy’s power was due to a thing that cannot be improvised, the training of officers and men.”

Prolonging Michael with the drive west delayed and weakened the attack in Flanders. Again the Germans broke through, smashing the Portuguese defenders and forcing the British from all of the ground they had paid so dearly for in 1917. However, French support enabled the British to save Hazebrouck, the rail junction that was the German goal. To draw the French reserves away from Flanders, the next attack was along the Aisne River where Nivelle had attacked the year before. Their success was dazzling. The defender’s front was immersed in a gas cloud fired from simple mortars. Within hours the Germans had reoccupied all the ground the French had taken by weeks of grinding, and they swept south through Champagne until they halted for resupply at the Marne River.

However, the Germans had lost 977,555 of their best men between March and the end of July, while Allied ranks were swelling with Americans. Their dwindling stock of horses were on the verge of starvation, and the ragged troops thought continually of food. One of the most effective propaganda handbills, which the British showered on the German lines, listed the rations received by prisoners of war. The German troops resented their officers’ better rations and reports of the ample meals at headquarters; in his memoirs, Ludendorff devotes six pages to defending officer’s rations and perks.After an attack, the survivors needed at least six weeks to recuperate, but now crack divisions were recommitted much sooner. Tens of thousands of men were skulking behind the lines. Determined to win, Hindenburg decided to expand the salient pointing toward Paris to strip more defenders from Flanders. The attack on Gouraud‘s French Fourth Army followed the now familiar scenario, but was met by a deceptive elastic defense and was decisively repelled at the French main line of resistance. Hindenburg still intended to make a decisive attack in Flanders, but before the Germans could strike, the French and Americans, led by light tanks, smashed through the right flank of the German salient on the Marne. The German defense was halfhearted; they had lost. Hindenburg went on the defensive. The Germans withdrew one by one from the salients created by their victories, evacuating the wounded and supplies, and retiring to shortened lines. Hindenburg hoped to hold a line until their enemies were ready to bargain.

Ludendorff’s breakdown

After the retreat from the Marne, Ludendorff became distraught, shrieking orders and often in tears. At dinner on 19 July, he responded to a suggestion of Hindenburg’s by shouting “I have already told you that is impossible”—Hindenburg led him from the room. On 8 August, the British completely surprised the Germans with a well-coordinated attack at Amiens, breaking well into the German lines. Most disquieting was that some German commanders surrendered their units and that reserves arriving at the front were taunted for prolonging the war. For Ludendorff, Amiens was the “black day in the history of the German Army.” Bauer and others wanted Ludendorff replaced, but Hindenburg stuck by his friend; he knew that “Many a time has the soldier’s calling exhausted strong characters.” A sympathetic physician who was Ludendorff’s friend persuaded him to leave headquarters temporarily to recuperate. (His breakdown is not mentioned in Hindenburg’s or his own memoirs.) On 12 August, Army Group von Boehn was created to firm up the defenses in the Somme sector. On 29 September Hindenburg and Ludendorff told the incredulous Kaiser that the war was lost and that they must have an immediate armistice.

Defeat and revolution

A new chancellor, Prince Maximilian of Baden, opened negotiations with President Woodrow Wilson, who would deal only with a democratic Germany. Prince Max told the Kaiser that he would resign unless Ludendorff was dismissed, but that Hindenburg was indispensable to hold the army together. On 26 October the Kaiser slated Ludendorff before curtly accepting his resignation—then rejecting Hindenburg’s. Afterwards, Ludendorff refused to share Hindenburg’s limousine. Colonel Bauer was retired. Hindenburg promptly replaced Ludendorff with Groener, the chief of staff of Army Group Kiev, which was assisting a breakaway Ukrainian State to fend off the Bolsheviks while receiving food and oil.

The Germans were losing their allies. In June the Austro-Hungarians in Italy attacked the Entente lines along the Piave River but were repelled decisively. On 24 October the Italians crossed the river in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. After a few days of resolute resistance the defense collapsed, weakened by the defection of men from the empire’s subject nations and by starvation: the men in their Sixth Army had an average weight of 120 lb (54 kg). On 14 October, Austria-Hungary asked for an armistice in Italy, but the fighting went on. In September the Entente and their Greek allies attacked in Macedonia. The Bulgarians begged for more Germans to stiffen their troops, but Hindenburg had none to spare. Many Bulgarian soldiers deserted as they retreated toward home, opening the road to Constantinople. The Austro-Hungarians were pushed back in Serbia, Albania and Montenegro, and signed an armistice on 3 November. The Ottomans were overextended, trying to defend Syria while exploiting the Russian collapse to move into the Caucasus, despite Hindenburg’s urging them to defend what they had. The British and Arabs broke through in September, capturing Damascus. The Armistice of Mudros was signed on 30 October.

Woodrow Wilson’s 23 October diplomatic note to Germany had indirectly called for the Kaiser’s abdication when it stated that the United States would negotiate only with representatives of the German people, not the monarchy. Wilhelm, determined to lead the Army home in the event of disturbances in Berlin, refused to abdicate.A week later, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhard Scheer without authorization made plans to dispatch the Imperial Fleet on a last battle against the British. Sailors in Kiel mutinied and set up workers’ and soldiers’ councils that spread quickly across Germany, sparking the German Revolution of 1918–1919. On 8 November, Hindenburg and the Kaiser met with 39 regimental officers at Spa. There he delivered a situation report and answered questions. Then Hindenburg left and Groener asked the officers to answer confidentially two questions about whether their troops would follow the Kaiser. The answers were decisive: the army would not. The Kaiser then agreed to abdicate without doing so at the time. In Berlin, however, Prince Max had already publicly announced the Kaiser’s abdication and his own resignation, and that the Social Democrat leader Friedrich Ebert, was the new chancellor. The Empire had crumbled all but bloodlessly. That evening Groener telephoned Ebert, whom he knew and trusted, to tell him that if the new government would fight Bolshevism and support the Army, then the Field Marshal would lead a disciplined army home. Hindenburg’s remaining in command bolstered the new government’s position.

The withdrawal became more fraught when the armistice obliged all German troops to leave Belgium, France, and Alsace-Lorraine in 14 days and to be behind the Rhine in 30 days. Stragglers would become prisoners. When the seven men from the executive committee of the soldiers’ council formed at Spa arrived at OHL they were greeted politely by a lieutenant colonel, who acknowledged their leadership. When they broached the march home he took them to the map room, explaining allocation of roads, and scheduling unit departures, billeting, and feeding. They agreed that the existing staffs should make these arrangements. To oversee the withdrawals OHL transferred headquarters from Belgium to Kassel in Germany, unsure how their officers would be received by the revolutionaries. They were greeted by the chairman of the workers’ and soldiers’ councils who proclaimed “Hindenburg belongs to the German nation.” His staff intended to billet him in the Kaiser’s palace there, Wilhelmshöhe. Hindenburg refused because they did not have the Kaiser’s permission, instead settling into a humble inn, thereby pleasing both his monarchist staff and the revolutionary masses. In the west 1.25 million men and 500,000 horses were brought home in the time allotted.

Hindenburg did not want to involve the Army in the defense of the new government against their civil enemies. Instead the Army supported the independent Freikorps (modeled on formations used in the Napoleonic wars), supplying them with weapons and equipment. In February 1919, OHL moved east to Kolberg to mount an offensive against impinging Soviet troops, but they were restrained by the Allied occupation administration, which in May 1919 ordered all German troops in the east home. On 25 June 1919, Hindenburg retired to Hanover once again. He settled in a splendid new villa, which was a gift of the city, despite his admittedly having “lost the greatest war in history”.

Military reputation

“Victory comes from movement” was Schlieffen’s principle for war. Hindenburg expounded on Schlieffen’s ideas as an instructor and later applied them during World War I. By employing such tactics, retreats and mobile defenses commanded by Hindenburg proved effective, and his Schwerpunkt attacks broke through the trench barrier on the Western Front. However, they failed to produce decisive victories because penetrating forces proved too slow to capitalize on their breakthroughs.

Hindenburg has undergone a historical revalution: his teaching of tactics and years on the General Staff have been less emphasised while he is remembered as a commander in Ludendorff’s shadow. Winston Churchill in 1923, depicted Hindenburg as a figurehead awed by the mystique of the General Staff, concluding that “Ludendorff throughout appears as the uncontested master.” Parkinson stated that he is a “beloved figurehead”,while to Stallings he is “an old military booby”. These judgements stem from Ludendorff, who was famous during the war and immediately thereafter wrote his comprehensive memoir with himself center stage. Hindenburg’s less detailed memoir never disputed his colleague’s claims, military decisions were made collectively not individually, and it is less useful to historians because it was written for general readers. Ludendorff continued emphasising his preeminence in print, which Hindenburg never disputed publicly.

Others did though, the OHL officers who testified before the Reichstag committee investigating the collapse of 1918 agreed that Hindenburg was always in command. He managed by setting objectives and appointing capable people to do their jobs, for instance “giving full scope to the intellectual powers” of Ludendorff. These subordinates often felt he did little, even though he was setting the overall course. Ludendorff may have overrated himself, repressing repeated demonstrations that he lacked resilience essential to command. Postwar he displayed poor judgment and an attraction to unusual ideas, contrasting with his former commander’s adaptation to changing times.

Most of their conferences were in private, but on 26 July 1918 the chief of staff of the Seventh Army, Fritz von Lossberg traveled to OHL to request permission to withdraw to a better position

Without knocking I entered Ludendorff’s office and found him loudly arguing with the field marshal. I assumed it was over the situation at the Seventh Army. In any case as soon as I entered the field marshall asked me to give my assessment of the situation at the Seventh Army. I described it in short terms and emphasized especially that based on my own observations I thought the condition of the troops was cause for serious concern. For the past few days the Seventh Army commanding general, the staff, and I had all been recommending a withdrawal from the increasingly untenable front lines. I told Hindenburg that I had come to Avesenes with the concurrence of the Seventh Army commanding general to secure such an order. The field marshall turned to Ludendorff, saying something to the effect of ‘Now Ludendorff, make sure that the order goes out immediately. ‘ He then left Ludendorff’s office rather upset.

— Lossberg

Hindenburg’s record as a commander starting in the field at Tannenberg, then leading four national armies, culminating with breaking the trench deadlock in the west, and then holding a defeated army together, is unmatched by other soldiers in World War I. However, military skill is only one component of the record: “… in general, the maladroit politics of Hindenburg and Ludendorff led directly to the collapse of 1918….”

Several treatments were devised. Acute conjunctivitis required alkaline eye irrigations over and over again until the symptoms lessened and abated. With the large numbers of patients admitted to hospital units, this meant the nurses started at one end of the ward and by the time they had reached the other end of the unit, it was time to begin a new round of treatments.5 For those who had breathed in the mustard gas, nurses at Base Hospital 32 helped devise a mixture of “guiacol, camphor, menthol, oil of thyme and eucalyptus [that forced the patients to expectorate the inflammatory material]. Patients received immediate relief, [respirations were less labored so] … healing was begun.”6

Several treatments were devised. Acute conjunctivitis required alkaline eye irrigations over and over again until the symptoms lessened and abated. With the large numbers of patients admitted to hospital units, this meant the nurses started at one end of the ward and by the time they had reached the other end of the unit, it was time to begin a new round of treatments.5 For those who had breathed in the mustard gas, nurses at Base Hospital 32 helped devise a mixture of “guiacol, camphor, menthol, oil of thyme and eucalyptus [that forced the patients to expectorate the inflammatory material]. Patients received immediate relief, [respirations were less labored so] … healing was begun.”6