This is a list of Northumberland Fusiliers battalions in World War I. When the First World War broke out in August 1914, the Northumberland Fusiliers, a fusilier infantry regiment of the British Army, consisted of 7 battalions, eventually expanding to 52 battalions, although not all existed at the same time, of which 29 served overseas. It was the second largest infantry regiment of the British Army during World War I, surpassed only by the 88 battalions of the London Regiment.

The Northumberland Fusiliers earned 67 battle honours and was awarded five Victoria Crosses but at the cost of over 16,000 soldiers killed in action, and many thousands wounded.The Northumberland Fusiliers mostly saw action in the main theatre of war, engaged in static trench warfare on the Western Front in Belgium and France, but also participated in fighting on the Macedonian front, the Gallipoli Campaign, the Sinai and Palestine Campaign and the Italian Front.

Pre-war

At the outbreak of the First World War, the Northumberland Fusiliers consisted of seven battalions.

Expansion

The expansion in battalions mostly came through two sources: the duplication of the Territorial Force battalions and the formation of Kitchener’s New Armies. Of the 45 battalions raised during the war, 10 were Territorial Force and 27 were New Army.

Territorial Force

In accordance with the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act 1907 which brought the Territorial Force into being, the TF was intended to be a home defence force for service during wartime and members could not be compelled to serve outside the country. However, on the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914, many members volunteered for Imperial Service. Therefore, TF units were split into 1st Line (liable for overseas service) and 2nd Line (home service for those unable or unwilling to serve overseas) units. 2nd Line units performed the home defence role, although in fact most of these were also posted abroad in due course. Later, a 3rd Line was formed to act as a reserve, providing trained replacements for the 1st and 2nd Line units. When 2nd Line battalions were formed, the 1st Line took on a fractional designation so, for example, 4th Battalion became 1/4th Battalion (first fourth) and its 2nd Line was designated 2/4th Battalion (second fourth); in due course the 3rd Line was formed as the 3/4th Battalion (third fourth).

In the summer of 1915, personnel of 2nd and 3rd line battalions who had not volunteered for overseas service were formed into Provisional Battalions. They were used to form Provisional Brigades and later Home Service divisions (71st, 72nd, and 73rd Divisions); on 1 January 1917 they became numbered battalions of line infantry regiments. In the case of the Northumberland Fusiliers, the 21st and 22nd Provisional Battalions became the 35th and 36th Battalions (T.F.) of the regiment

New Army

Kitchener was one of the few people in 1914 to realize that the war was not going to be a short one; he believed that it would last three years and would require an army of 70 divisions. He eschewed the Territorial Force – partly due to the limitations imposed by its terms of service but also due to the poor impression he formed when observing the French Territorials in the Franco-Prussian War – and did not make use of the framework envisioned by Haldane. He launched his appeal for 100,000 volunteers on 7 August 1914 to form a New Army of six divisions (and support units) and within a few days this target had been reached; by the end of September, half a million volunteers had come forward to form the New Armies

Each of the 69 line infantry regiments raised one battalion for the First (K1) and for the Second New Armies (K2) designated as Service battalions and numbered after the existing Territorial Force battalions (so 8th and 9th (Service) Battalions for the Northumberland Fusiliers). This rigid structure did not take account of the differing ability of regiments to raise troops based upon the population of their recruiting areas. Therefore, the Third New Army (K3) had a much higher proportion of battalions from the more populous north of England, notably Cheshire, Lancashire, Yorkshire, Durham and Northumberland (10th, 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th (Service) Battalions). The Fourth New Army (K4) was formed from men of the Reserve and Special Reserve battalions which were over establishment. Originally formed into the 30th – 35th Divisions, these were broken up so the battalions could train recruits and send drafts to the first three New Armies. The regiment raised the 15th (Reserve) Battalion in this manner.

While the first four New Armies were being raised, a number of units were also being raised by committees in cities and towns, and by other organizations and individuals – the Pals battalions. These were housed, clothed and fed by their committees until the War Office took them over in 1915 and the raisers’ expenses were refunded. These units formed the Fifth and Sixth New Armies (later called the new Fourth and Fifth New Armies when the original Fourth New Army was broken up). The Northumberland Fusiliers raised the largest number of pals battalions of any regiment, notably including the Tyneside Scottish and Tyneside Irish Brigades: 16th (Newcastle), 17th (NER Pioneers), 18th (1st Tyneside Pioneers), 19th (2nd Tyneside Pioneers), 20th (1st Tyneside Scottish), 21st (2nd Tyneside Scottish), 22nd (3rd Tyneside Scottish), 23rd (4th Tyneside Scottish), 24th (1st Tyneside Irish), 25th (2nd Tyneside Irish), 26th (3rd Tyneside Irish), and 27th (4th Tyneside Irish) battalions.

The locally recruited – pals – battalions formed depot companies and in 1915 these were grouped into local reserve battalions to provide reinforcements for their parents. The regiment formed 28th, 29th (Tyneside Scottish), 30th (Tyneside Irish), 31st, 32nd, 33rd (Tyneside Scottish), and 34th (Tyneside Irish) Reserve Battalions.

The regiment formed eight other battalions. The 37th (Home Service) Battalion was formed in April 1918 to replace the 36th Battalion when it moved to the Western Front. The 38th Battalion was formed in June 1918, but was absorbed into the 22nd Battalion before the end of the month.

The regiment raised three Garrison Battalions (1st, 2nd, and 3rd) of officers and men unfit for active service but considered fit for garrison duty at home and overseas, thereby releasing fitter troops for front line service.

In May 1917, the Training Reserve was reorganized with the battalions becoming more specialized in their training. Young Soldier Battalions took in recruits aged 18 years and one month and, after basic training, posted them to one of two linked Graduated Battalions. Eventually, 23 Young Soldier Battalions and 46 Graduated Battalions were formed. On 27 October 1917, these were allocated to 23 infantry regiments and thereby the Northumberland Fusiliers gained the 51st (Graduated), 52nd (Graduated) and 53rd (Young Soldier) Battalions.

Reserve battalions

A number of reserve battalions served during the war. They recruited and trained drafts for the active service units and were designated by use of (Reserve) after the battalion number. These had a number of different origins and had a variety of fates.

Special Reserve battalions

The Childers Reforms of 1881 created regimental districts, each allocated a two-battalion regiment, usually bearing a “county” title. Existing two-battalion regiments of foot (1st to 25th inclusive) were redesignated, whereas the single-battalion foot regiments were paired to become the 1st or 2nd battalions of the new regiments. At the same time the existing militia and rifle volunteer units of the district became battalions of their regiments, the militia numbered after the regulars – thus 3rd (Millitia) Battalion, 4th (Millitia) Battalion, etc. – and the volunteers in a separate sequence – 1st Volunteer Battalion, 2nd Volunteer Battalion, etc. As the 5th (Northumberland) (Fusiliers) Regiment of Foot already had two battalions, it simply became the Northumberland Fusiliers as the county regiment of Northumberland. The Northumberland Light Infantry Militia became the 3rd (Militia) Battalion and the rifle volunteers formed the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Volunteer Battalions of the regiment.

Further reforms by Haldane in 1908 saw the militia transferred to a new “Special Reserve” as “Reserve” – 3rd battalions – or “Extra Reserve” – 4th and subsequent – battalions. The volunteer battalions were renumbered in the same sequence as the regulars and millitia. Hence, the 3rd (Millitia) Battalion became the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion and the volunteers became the 4th, 5th and 6th Battalions of the Northumberland Fusiliers.

Almost all of the Special Reserve battalions remained in the United Kingdom throughout the war, training replacements and providing drafts to the regular battalions. The 3rd (Reserve) Battalion remained part of the regiment as a training unit until the end of the war.

2nd Reserve battalions[edit]

On 8 October 1914, each Reserve and Extra Reserve battalion of the line infantry regiments were instructed to form a Service battalion. The battalions thus raised, including the 15th (Service) Battalion, were used to form the divisions of Kitchener’s Fourth New Army. The divisions were never fully formed; the need for trained reinforcements for the first three New Armies meant that they were broken up and the infantry battalions were used to provide and train reinforcements. On 10 April 1915, the infantry battalions became reserve formations to be known as 2nd Reserve battalions (in the sense that they were second to the original Reserve and Extra Reserve battalions). The 15th Battalion became the 15th (Reserve) Battalion and provided replacements for the 8th – 14th battalions.

The introduction of conscription caused a reorganisation of the reserve battalions as the regimental system could not cope with the number of new recruits. A new, centralized, system was put in place, called The Training Reserve. On 1 September 1916, the 15th Battalion became part of the new organisation.

Local Reserve battalions[edit]

The locally recruited Service battalions of the Fifth and Sixth New Armies – the Pals battalions – formed depot companies and in 1915 these were grouped into Local Reserve battalions to provide reinforcements for their parents. Like the 2nd Reserve battalions, they became part of the Training Reserve on 1 September 1916.

Territorial Force Reserve battalions

Almost all Territorial Force battalions had formed a 3rd Line – designated with the fractional 3/ – by June 1915; they supplied reinforcements to their parent 1st and 2nd Lines. In the autumn of 1915 they were brought together in 14 Third Line Groups, one for each of the pre-war T.F. divisions– those of the Northumberland Fusiliers joining the Northumbrian Third Line Group, along with those of the East Yorkshire Regiment then Green Howards,and the Durham Light Infantry.

In April 1916 they dropped the fractional designation and became Reserve Battalions T.F. On 1 September 1916 the reserve territorial battalions of each regiment were amalgamated into a single unit (or two units in certain large regiments, for example the Manchester Regiment’s 5th and 8th Reserve Battalions). At the same time, the Third Line Groups were renamed as Reserve Brigades T.F. The Northumbrian Reserve Brigade T.F. commanded 4th (Reserve) Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers, 4th (Reserve) Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment,4th (Reserve) Battalion, Green Howards, and 5th (Reserve) Battalion, Durham Light Infantry in the Hornsea area as part of the Humber Garrison.

Along with the Special Reserve battalions, the T.F. Reserve battalions remained as regimental reserves. New recruits were posted to them first until they were up to strength, then to the Training Reserve. When drafts were needed for the overseas units, they were taken first from the regimental reserves; if there were insufficient trained replacements then recourse was made to the Training Reserve.

Battalions

1st Battalion

The 1st Battalion was a regular army battalion, stationed in Portsmouth at the outbreak of World War I. It was assigned to the 9th Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division and remained with it throughout the war. It landed at Le Havre on 14 August 1914 and remained on the Western Front until the Armistice with Germany. It fought in the following major battles:Battle of MonsFirst Battle of the AisneFirst Battle of YpresBattle of the Somme (1916)Battle of Arras (1917)Third Battle of YpresFirst Battle of the Somme (1918)Battle of the Lys (1918)Second Battle of the Somme (1918)Battles of the Hindenburg LineFinal Advance in Picardy

2nd Battalion

The 2nd Battalion was a regular army battalion, stationed in Sabathu, India as part of the 9th (Sirhind) Brigade, 3rd (Lahore) Division at the outbreak of World War I.It departed Karachi on 20 November 1914, arrived at Plymouth on 22 December and proceeded to Winchester where it joined the 84th Brigade, 28th Division. It moved to the Western Front in January 1915 and on to the Salonika front in November. In June 1918, it left 28th Division and was transferred to France where it joined the 150th Brigade, 50th (Northumbrian) Division for the rest of the war. During the war, it fought in the following battles with 28th Division:Second Battle of YpresBattle of LoosStruma

and with 50th Division:Battles of the Hindenburg LineFinal Advance in Picardy

3rd (Reserve) Battalion

The 3rd Battalion was a Special Reserve battalion based in Newcastle upon Tyne at the outbreak of war. In August 1914 it moved to East Boldon (near Sunderland) where it remained throughout the war as part of the Tyne Garrison and provided drafts to the regular (1st and 2nd) battalions.The battalion was disembodied on 29 July 1919 (personnel transferred to the 1st Battalion on 12 July) but was not formally disbanded until April 1953.

4th Battalion (T.F.)

In peacetime, the 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th Battalions formed the Northumberland Brigade, Northumbrian Division. They were mobilised on the outbreak of the war and were posted to the Tyne Defences. The 4th Battalion was redesignated as 1/4th Battalion with the formation of the 2nd Line battalion in November 1914. In April 1915, the brigade was posted to France and on 14 May was redesignated as 149th (Northumberland) Brigade in 50th (Northumbrian) Division. On 15 July 1918, the battalion was reduced in strength to a cadre and transferred to Lines of Communication duties. On 16 August 1918, it was assigned to the 118th Brigade, 39th Division. It was disbanded on 10 November 1918.[8] It took part in the following battles with 50th Division:Second Battle of YpresBattle of the Somme (1916)Battle of Arras (1917)Third Battle of YpresFirst Battle of the Somme (1918)Battle of the Lys (1918)

This history of the 5th Battalion – redesignated as 1/5th Battalion with the formation of the 2nd Line battalion in November 1914 – was identical to that of the 4th Battalion.

6th Battalion (T.F.)

This history of the 6th Battalion – redesignated as 1/6th Battalion with the formation of the 2nd Line battalion in December 1914 – was identical to that of the 4th Battalion.

7th Battalion (T.F.)

This history of the 7th Battalion – redesignated as 1/7th Battalion with the formation of the 2nd Line battalion in September 1914 – was identical to that of the 4th Battalion until February 1918. British divisions on the Western Front were reduced from a 12-battalion to a 9-battalion basis in February 1918 (brigades from four to three battalions) and the 1/7th Battalion was transferred to 42nd (East Lancashire) Division as Pioneers on 12 February 1918 where it remained for the rest of the war.[8] It took part in the following battles with 50th Division:Second Battle of YpresBattle of the Somme (1916)Battle of Arras (1917)Third Battle of YpresFirst Battle of the Somme (1918)Second Battle of the Somme (1918)

and with the 42nd Division:Battles of the Hindenburg LineFinal Advance in Picardy

2/4th, 2/5th and 2/6th Battalions (T.F.)

The 2/4th and 2/5th Battalions were formed at Blyth in November 1914 and the 2/6th Battalion at Newcastle on 28 December 1914. In January 1915 they were assigned to the 188th (2/1st Northumberland) Brigade, 63rd (2nd Northumbrian) Divisionat Swalwell Camp near Newcastle. In November 1915, the brigade moved to York and in July 1916 the Division was broken up; the battalions remained with the brigade at York. In November 1916, the battalions were assigned to the 217th Brigade, 72nd Division at Clevedon. They moved to Northampton in January 1917 and to Ipswich in May.The 2/5th and 2/6th Battalions were disbanded on 6 and 5 December 1917 and the 2/4th Battalion on 8 April 1918 at Ipswich.

2/7th Battalion (T.F.)

The 2/7th Battalion was formed at Alnwick on 26 September 1914 and assigned to the 188th (2/1st Northumberland) Brigade, 63rd (2nd Northumbrian) Division in January 1915. In January 1917 the battalion moved to Egypt as a garrison battalion. It was disbanded on 15 September 1919.

3/4th, 3/5th, 3/6th and 3/7th Battalions (T.F.)

The 3rd Line battalions were formed in June 1915 at Hexham (3/4th), Newcastle (3/5th and 3/6th) and Alnwick (3/7th). On 8 April 1916 they became Reserve Battalions at Catterick: the 3/4th Battalion was redesignated as 4th (Reserve) Battalion, 3/5th as 5th (Reserve), 3/6th as 6th (Reserve), and 3/7th as 7th (Reserve). On 1 September 1916, the 4th (Reserve) Battalion absorbed the other three. After March 1917 it was at Atwick, Hornsea, to South Dalton in early 1918 and by July 1918 was at Rowlston (near Hornsea) where it remained in the Northumbrian Reserve Infantry Brigade until the end of the war. It was disbanded on 17 April 1919 at Rowlston.

8th (Service) Battalion

The 8th (Service) Battalion was formed at Newcastle on 19 August 1914. as part of Kitchener’s First New Army – K1 – and was assigned to the 34th Brigade, 11th (Northern) Division at Grantham. In July 1915 it departed for the Mediterranean and landed at Gallipoli on 7 August. In January 1916 it moved to Egypt where it formed part of the Suez Canal Defences, and in July to France where it spent the rest of the war (still in 34th Brigade, 11th Division) It was disbanded on 27 June 1919 at Newcastle. It fought in the following battles:Battles of Suvla including the Landing at Suvla Bay and the Battle of Scimitar HillBattle of the Somme (1916)Battle of Messines (1917)Third Battle of YpresBattle of Arras (1918)Battles of the Hindenburg LineFinal Advance in Picardy

9th (Northumberland Hussars) Battalion

The 9th (Service) Battalion was formed at Newcastle on 8 September 1914 as part of Kitchener’s Second New Army – K2 – and was assigned to the 52nd Brigade, 17th (Northern) Division at Wareham. In July 1915 it moved to the Western Front where it was to remain until the end of the war. On 3 August 1917, it was transferred to the 103rd Brigade, 34th Division.On 25 September 1917, it absorbed the 2/1st Northumberland Hussars and became the 9th (Northumberland Hussars) Battalion. On 26 May 1918, it was transferred to the 183rd Brigade, 61st (2nd South Midland) Division. It was disbanded on 1 November 1919 in France. It fought in the following battles with 17th Division:Battle of the Somme (1916)Battle of Arras (1917)

with the 34th Division:Third Battle of YpresFirst Battle of the Somme (1918)Battle of the Lys (1918)

and with the 61st Division:Final Advance in Picardy

10th and 11th (Service) Battalions

The 10th and 11th (Service) Battalions were formed at Newcastle on 22 September 1914 as part of Kitchener’s Third New Army – K3 – and were assigned to the 68th Brigade, 23rd Division at Bullswater, near Frensham. In August 1915 they moved to the Western Front and in November 1917 to the Italian Front, where they remained, still in 68th Brigade, 23rd Division. The 10th Battalion was reduced to cadre in Italy in 1918. They were disbanded in Newcastle on 11 and 25 June 1919. They fought in the following major battles:Battle of the Somme (1916)Battle of Messines (1917)Third Battle of YpresBattle of the PiaveBattle of Vittorio Veneto

12th and 13th (Service) Battalions

The 12th and 13th (Service) Battalions were formed at Newcastle on 22 September 1914, also as part of Kitchener’s Third New Army – K3 – and were assigned to the 62nd Brigade, 21st Division at Halton Park. They moved to France in September 1915. They were amalgamated on 1 August 1917 as the 12th/13th (Service) Battalion.The combined battalion remained in 62nd Brigade, 21st Division on the Western Front for the rest of the war.The 12th/13th Battalion was disbanded at Catterick on 1 May 1919. They fought in the following battles:Battle of LoosBattle of the Somme (1916)Battle of Arras (1917)Third Battle of YpresBattle of Cambrai (1917)First Battle of the Somme (1918)Battle of the Lys (1918)Second Battle of the Somme (1918)Battles of the Hindenburg LineFinal Advance in Picardy

14th (Service) Battalion (Pioneers)

The 14th (Service) Battalion was formed at Newcastle on 22 September 1914, also as part of Kitchener’s Third New Army – K3 – and was assigned to the 21st Division at Halton Park, initially as Army Troops, but from February 1915 as a Pioneer Battalion.It moved to France in September 1915 where it remained with 21st Division on the Western Front for the rest of the war. The 14th Battalion was disbanded on 16 July 1919 in France. It took part in the following battles:Battle of LoosBattle of the Somme (1916)Battle of Arras (1917)Third Battle of YpresBattle of Cambrai (1917)First Battle of the Somme (1918)Battle of the Lys (1918)Second Battle of the Somme (1918)Battles of the Hindenburg LineFinal Advance in Picardy

15th (Reserve) Battalion

The 15th (Service) Battalion was formed at Darlington in October 1914, as part of Kitchener’s original Fourth New Army – K4 – and was assigned to the 89th Brigade, 30th Division. The Fourth New Army was not fully formed when the decision was made to use it to provide replacements for the first three New Armies (K1, K2 and K3). The divisions were broken up on 10 April 1915; the infantry brigades and battalions became reserve formations and the other divisional troops were transferred to the divisions of the Fifth and Sixth New Armies.15th (Service) Battalion became a 2nd Reserve battalion and was redesignated as 15th (Reserve) Battalion. It remained in 89th Brigade which now became 1st Reserve Brigade. It provided replacements for the 8th – 14th battalions In September 1916, it was absorbed by the other Training Reserve battalions of the 1st Reserve Brigade.[8][39]

16th (Service) Battalion (Newcastle)

The 16th was a Pals battalion, raised in Newcastle in September 1914 by the Newcastle and Gateshead Chamber of Commerce. It was taken over be the War Office in April 1915 and in June 1915, the 16th (Newcastle) Battalion was assigned to the 96th Brigade, 32nd Division at Catterick. On 22 November 1915, it landed at Boulogne and remained on the Western Front until 7 February 1918 when it was disbanded at Elverdinghe. Its personnel were transferred to the T.F. battalions: A Company to 1/4th, B Company to 1/5th and C Company to 1/6th in 50th Division, D Company to 1/7th in 42nd Division and the remainder to the 13th Entrenching Battalion. The battalion fought in the following battles:Battle of the Somme (1916) (including the battles of Albert, Bazentin Ridge, Ancre Heights and Ancre)

17th (Service) Battalion (N.E.R. Pioneers)

The 17th Battalion was also a Pals battalion, raised by the North Eastern Railway at Hull in September 1914. It became a pioneer battalion on 11 January 1915 and was assigned to the 32nd Division at Catterick in June. It was taken over by the War Office on 1 September 1915, and landed at Havre on 21 November with 32nd Division. On 19 October 1916 it moved to GHQ Railway Construction Troops, 2 September 1917 back to 32nd Division, 15 November back to GHQ Railway Construction Troops and finally on 31 May 1918 to 52nd (Lowland) Division as Pioneer Battalion where it remained until the end of the war It was disbanded at Newcastle on 27 June 1919. The battalion took part in the following battles with 32nd Division:Battle of the Somme (1916) (including the battles of Albert, Bazentin Ridge, Ancre Heights and Ancre)

and with 52nd Division:Second Battle of the Somme (1918)Battle of Arras (1918)Battles of the Hindenburg LineFinal Advance in Artois

18th (Service) Battalion (1st Tyneside Pioneers)

The 18th Battalion was a Pals battalion raised in Newcastle on 15 October 1914 by the Lord Mayor and City. On 8 February 1915 it became a Pioneer Battalion and in July joined 34th Division at Kirkby Malzeard. It was taken over by the War Office on 15 August 1915, and landed at Havre on 8 January 1916 with 34th Division. It was reduced to cadre strength on 18 May 1918. On 17 June 1918, it was transferred to the infantry and assigned to the 116th Brigade, 39th Division. It moved again on 29 July 1918, when it was assigned to the 118th Brigade, 39th Division. On 16 August 1918, it was assigned as Divisional Troops to the 66th Division. Its last move was on 20 September 1918, when it was assigned to the 197th Brigade as Lines of Communication troops. It was disbanded in France in June 1919.While attached to 34th Division, it saw action at:Battle of the Somme (1916)Battle of Arras (1917)Third Battle of Ypres First Battle of the Somme (1918)Battle of the Lys (1918)

19th (Service) Battalion (2nd Tyneside Pioneers)

The 19th Battalion was a Pals battalion raised in Newcastle on 16 November 1914 by the Lord Mayor and City. On 8 February 1915 it became a Pioneer Battalion and in July joined 35th Division at Masham. It was taken over by the War Office in August 1915, and landed at Havre on 29 January 1916 with 35th Division. It remained with the 35th Division as Pioneers on the Western Front for the rest of the war. 19th Battalion was disbanded on 30 April 1919 at Ripon. The 35th Division was involved in the following battles:Battle of the Somme (1916)Third Battle of YpresFirst Battle of the Somme (1918)Final Advance in Flanders

20th, 21st, 22nd and 23rd (Service) Battalions (Tyneside Scottish)

The 1st – 4th Tyneside Scottish Battalions were Pals battalions raised in Newcastle by the Lord Mayor and City on 14 October (1st), 26 September (2nd), 5 November (3rd) and 16 November 1914 (4th). In March 1915 they moved to Alnwick and together they formed 102nd (Tyneside Scottish) Brigade, 34th Division in June 1915. They were taken over by the War Office on 15 August 1915, moved to Salisbury Plain at the end of the month and crossed to France in January 1916.Due to extremely heavy casualties suffered during the attack at La Boiselle on 1 July 1916,[n] the Brigade was attached to the 37th Division between 6 July and 22 August 1916 in exchange for 111th Brigade.

British divisions on the Western Front were reduced from a 12-battalion to a 9-battalion basis in February 1918 (brigades from four to three battalions): the 20th and 21st Battalions were disbanded on 3 February and the 25th Battalion joined from the 103rd (Tyneside Irish) Brigade on the same date. As a result of the losses suffered in the Ludendorf Offensive (First Battle of the Somme and Battle of the Lys), 102nd Brigade had to be extensively reorganized. On 16 May 1918, the 23rd Battalion was reduced to cadre and transferred to Lines of Communication duties; it joined 116th Brigade, 39th Division on 17 June, to 66th Division on 16 August and to 197th Brigade on 20 September where it remained for the rest of the war. The 22nd Battalion was likewise reduced to cadre on 17 May; it returned to England on 18 June with 16th Division. It absorbed the new 38th Battalion at Margate and was posted to 48th Brigade, 16th Division at Aldershot. It returned to France in July where it remained for the rest of the war.The 22nd Battalion was disbanded on 14 June 1919 at Catterick, and the 23rd Battalion in June 1919 in France.

While part of the 34th Division, the Tyneside Scottish took part in the following major actions:Battle of the Somme (1916) (Battle of Albert only)Battle of Arras (1917)Third Battle of YpresFirst Battle of the Somme (1918)Battle of the Lys (1918)

While part of the 16th Division, the 22nd Battalion also took part in the Final Advance in Artois and Flanders.

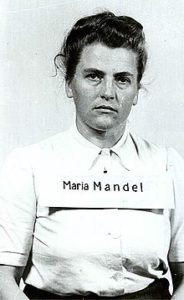

24th, 25th, 26th and 27th (Service) Battalions (Tyneside Irish)

A support company of the Tyneside Irish Brigade advancing on 1 July 1916.

The 1st – 4th Tyneside Irish Battalions were Pals battalions raised in Newcastle by the Lord Mayor and City on 14 November (1st), 9 November (2nd), 23 November 1914 (3rd) and 5 January 1915 (4th). In March 1915 they moved to Woolsington and together they formed 103rd (Tyneside Irish) Brigade, 34th Division in June 1915. They were taken over by the War Office on 27 August 1915, moved to Salisbury Plain at the end of the month and crossed to France in January 1916.Due to extremely heavy casualties suffered during the attack at La Boiselle on 1 July 1916, the Brigade was attached to the 37th Division between 6 July and 22 August 1916 in exchange for 112th Brigade.

On 10 August 1917, the 24th and 27th Battalions were amalgamated as the 24th/27th Battalion. British divisions on the Western Front were reduced from a 12-battalion to a 9-battalion basis in February 1918 (brigades from four to three battalions): the 25th Battalion joined the 102nd (Tyneside Scottish) Brigade on 3 February and the 24th/27th and 26th Battalions were disbanded on 26 February.[3] As a result of the losses suffered in the Ludendorf Offensive (First Battle of the Somme and Battle of the Lys), 102nd Brigade had to be extensively reorganized. On 16 May 1918, the 25th Battalion was reduced to cadre and transferred to Lines of Communication duties; it joined 39th Division on 17 June, to 66th Division on 16 August and to 197th Brigade on 20 September where it remained for the rest of the war. 25th Battalion was disbanded in France in June 1919.

While part of the 34th Division, the Tyneside Irish took part in the following major actions:Battle of the Somme (1916) – Battle of Albert Battle of Arras (1917)Third Battle of YpresFirst Battle of the Somme (1918)Battle of the Lys (1918)

28th (Reserve) Battalion)

The 28th Battalion was formed at Cramlington in July 1915 from the depot companies of the 18th and 19th Battalions as a Local Reserve battalion. In November 1915 it was at Ripon in the 19th Reserve Brigade, and in December to Harrogate. On 1 September 1916, it was absorbed by the Training Reserve Battalions of 19th Reserve Brigade.

29th (Reserve) Battalion (Tyneside Scottish)

The 29th Battalion was formed at Alnwick in July 1915 from the depot companies of the 20th, 21st, 22nd and 23rd Battalions as a Local Reserve battalion In January 1916 it was at Barnards Castle in the 20th Reserve Brigade, and in April to Hornsea. On 1 September 1916, it became 84th Training Reserve Battalion, 20th Reserve Brigade at Hornsea.

30th (Reserve) Battalion (Tyneside Irish)

The 30th Battalion was formed at Woolsington in July 1915 from the depot companies of the 24th, 25th, 26th and 27th Battalions as a Local Reserve battalion.In November 1915 it was at Richmond in the 20th Reserve Brigade, and in December to Catterick. On 1 September 1916, it became 85th Training Reserve Battalion, 20th Reserve Brigade at Hornsea.

31st (Reserve) Battalion[edit]

The 31st Battalion was formed at Catterick in November 1915 from the depot companies of the 16th Battalion as a Local Reserve battalion in the 20th Reserve Brigade. In April 1916 it moved to Hornsea and on 1 September 1916, it became 86th Training Reserve Battalion, 20th Reserve Brigade at Hornsea.

32nd (Reserve) Battalion[edit]

The 32nd Battalion was formed at Ripon in November 1915 from the depot companies of the 17th Battalion as a Local Reserve battalion in the 19th Reserve Brigade. In December 1915 it moved to Harrogate and in June 1916 to Usworth, Washington. On 1 September 1916, it became 80th Training Reserve Battalion, 19th Reserve Brigade at Newcastle.

33rd (Reserve) Battalion (Tyneside Scottish)

The 33rd Battalion was formed at Hornsea in June 1916 from the 29th Battalion as a Local Reserve battalion. On 1 September 1916, it was absorbed into the Training Reserve Battalions of 20th Reserve Brigade at Hornsea.

34th (Reserve) Battalion (Tyneside Irish)

The 34th Battalion was formed at Hornsea in June 1916 from the 30th Battalion as a Local Reserve battalion.On 1 September 1916, it was absorbed into the Training Reserve Battalions of 20th Reserve Brigade at Hornsea.

35th Battalion (T.F.)

The 21st Provisional Battalion (T.F.) was formed about June 1915 from the Home Service personnel of the T.F. Battalions. On 1 January 1917 it became the 35th Battalion (T.F.) of the regiment at Herne Bay in 227th Brigade. It remained at Herne Bay until early 1918 when it moved to Westleton where it remained until the end of the war[3] with 227th Brigade. The 35th Battalion was disbanded on 4 September 1919 at Saxmundham.

36th Battalion (T.F.)

The 22nd Provisional Battalion (T.F.) was formed about June 1915 from the Home Service personnel of the T.F. Battalions. On 1 January 1917 it became the 36th Battalion (T.F.) of the regiment at St. Osyth in 222nd Brigade. It moved to Ramsgate in March 1917 and to Margate in April 1918. On 27 April it became a Garrison Guard battalion and went to France in May where it joined 178th Brigade, 59th (2nd North Midland) Division. The “Garrison Guard” title was dropped by July. It was still with 178th Brigade, 59th Division at the end of the war.It was reduced to cadre on 5 November 1919 in France and disbanded on 28 November in Northern Command. It took part in the following battles:Second Battle of the Somme (1918)Final Advance in Artois and Flanders

37th (Home Service) Battalion

The 37th (Home Service) Battalion was formed on 27 April 1918 at Margate to replace the 36th Battalion (T.F.) in 222nd Brigade. It remained at Margate in 222nd Brigade until the end of the war. It was disbanded on 25 June 1919 at Canterbury.

38th Battalion[edit]

The short-lived 38th Battalion was formed at Margate on 1 June 1918. It was absorbed by the 22nd Battalion (3rd Tyneside Scottish) on 18 June.

1st Garrison Battalion

The 1st Garrison Battalion was formed in August 1915 and then sent to the island of Malta on Garrison duties. It was disbanded in India on 4 March 1920.

2nd Garrison Battalion

The 2nd Garrison Battalion was formed at Newcastle in October 1915, it was then sent to India in February 1916. It joined Sialkot Brigade, 2nd (Rawalpindi) Division, moved to Poona Brigade, Poona Divisional Area in March 1917and to Ahmednager Brigade in October where it remained until the end of the war. It was disbanded in the UK on 19 January 1920.

3rd (Home Service) Garrison Battalion

The 3rd (Home Service) Garrison Battalion was formed at Sunderland about March 1916. It sent to Ireland in 1917 and was at Belfast in 1918. It was disbanded in Ireland on 24 June 1919.

51st (Graduated) Battalion

The 51st (Graduated) Battalion was formed on 27 October 1917 by the redesignation of the 238th Graduated Battalion, Training Reserve. It originated as the new 4th Training Reserve Battalion. It was in 206th (2nd Essex) Brigade, 69th (2nd East Anglian) Division at Welbeck. Early in 1918 it moved to Middlesbrough and later to Guisborough where it remained until the end of the war. The battalion was converted to a service battalion as 51st (Service) Battalion on 8 February 1919. It was reduced to cadre in 1919 before being disbanded on the Rhine on 28 March 1920.

52nd (Graduated) Battalion

The 52nd (Graduated) Battalion was formed on 27 October 1917 by the redesignation of the 276th Graduated Battalion, Training Reserve. It originated as the 3rd Training Reserve Battalion (formerly 10th (Reserve) Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment). It was in 200th (2/1st Surrey) Brigade, 67th (2nd Home Counties) Division at Canterbury. On 5 March 1918 it joined 206th Brigade, 69th Division at Barnards Castle and in June to Guisborough where it remained until the end of the war.The battalion was converted to a service battalion as 52nd (Service) Battalion on 8 February 1919. It was disbanded on the Rhine on 28 March 1920.

53rd (Young Soldier) Battalion

The 53rd (Young Soldier) Battalion was formed on 27 October 1917 by the redesignation of the 5th Young Soldier Battalion, Training Reserve. It originated as the 5th Training Reserve Battalion (formerly 10th (Reserve) Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment) at Rugeley, Cannock Chase. It remained in the United Kingdom throughout the war.[84] The battalion was converted to a service battalion as 53rd (Service) Battalion on 8 February 1919. It was disbanded on the Rhine on 26 October 1919.

Post-war

The Northumberland Fusiliers continued to raise new battalions after the end of the war: the 39th (Service) Battalion on 10 May 1919 and the 40th (Service) Battalion in September 1919. They were disbanded in France on 5 March 1920 and 19 September 1919, respectively.

All of the war-raised battalions had been disbanded by the end of March 1920. The 1st Line Territorial Force battalions were reconstituted on 7 February 1920 as part of the new Territorial Armywhere they once again formed the Northumberland Brigade in the Northumbrian Division. Therefore, the Northumberland Fusiliers entered the inter-war period with

- 1st Battalion

- 2nd Battalion

- 3rd Battalion (Militia)

- 4th Battalion (T.A.)

- 5th Battalion (T.A.)

- 6th Battalion (T.A.)

- 7th Battalion (T.A.)