For weary refugees and prisoners of war, treasure was a bar of soap and a handkerchief.

Volunteer Ann Curtis, from Suffolk, knew a lot about this kind of treasure. She put in 88 hours of needlework to create individual treasure bags.

“About 1200 officers and men arriving in Switzerland for internment from Germany were provided with chintz treasure bags containing washing materials, handkerchiefs etc, which were very popular,” reported the Red Cross.

“Indeed, many of the bags were recognised three months later at the general repatriation doing duty as hand luggage.

“About 3,000 of these fitted bags were handed to the prisoners passing through Switzerland on their way home from Germany after the Armistice.

“Another 550 were given to civilian refugees passing through from Austria, Poland, Hungary, etc and were quite invaluable to the women, many of whom were accompanied by small children.”

The organisation relied on hundreds of volunteers like Ann to stitch, sew and knit products for prisoners of war and hospital and wards.

The Red Cross issued material and standard patterns to follow. Hour after hour, knitting needles clicked and scissors snipped in communities across the UK.

When she wasn’t sewing treasure bags, Ann Curtis made hot water bottle covers.

Eighty-three-year-old volunteer Martha Antobus in Cheshire knitted 40 pairs of woolly socks.

And Mr Stevenette, described as “an old gentleman of over 80, knitted 44 mufflers – his knitting exceeded all other workers.”

There was such huge demand for these items that in 1915 the Red Cross set up the Central Work Rooms. Throughout the war over 1,200 women worked in these London offices. They produced 705,500 bandages and 75,530 garments ranging from hot water bottle covers, pyjamas, dressing gowns and kitbags to pants, surgeon’s gowns, socks and pillow cases.

They used flannel, sheep’s wool and even some dog’s wool made from long-haired breeds such as Pekinese and Pomeranians.

Sewing all these garments was not without its perils. VAD nurse Helen Beale wrote to her family:

“We are very pleased this evening as the pin that the girl swallowed on Wednesday last has just emerged safely – she has been having cotton wool sandwiches and suet pudding etc. It really is rather wonderful to think that it has travelled so far inside her without pricking!”

Sometimes ‘doing your bit’ meant getting your feet wet.

During both world wars you could find children and adults doing their bit by getting muddy and wet in peat bogs. They were collecting sphagnum moss, a small, bright green plant that was often called ‘bog moss’. It was a time-consuming, cold and uncomfortable job.

The moss was harvested and dried on an industrial scale, particularly during the First World War. In those days, before antibiotics, this moss was mildly antiseptic and could soak up a lot of fluid.

In short, it was a brilliant wound dressing.

In Ireland, Red Cross sphagnum moss centres were set up in every county. Women volunteers collected enough sphagnum moss to make close to one million dressings.

Ethel Adams was one of these women. Volunteering in County Tyrone, Ethel gathered sphagnum moss almost full time. She picked, gathered and dried the moss, sending it off to the Red Cross depots in Belfast and Armagh. She paid for the postage herself as another way to support the cause.

“In County Tyrone, sphagnum moss depots did continuous work from 1916 to October 1918,” recorded the Red Cross journal.

“Sending their supplies to Derry and Belfast, they were manufactured into dressings, the moss from this county having been considered of exceptionally good quality.”

Ethel did not just collect moss on her own – she organised a local group to gather as much as possible.

As if that wasn’t enough, she then volunteered at the Belfast moss depot. Here she clocked up 100 hours of volunteering in just three months. Ethel received a war workers badge in recognition of her efforts.

If you think hospital food is bad today, spare a thought for patients during the First World War.

Hospital caterers had a budget of just 20 pence per day to cook up a varied diet for one patient. Anything more expensive was considered an extravagance.

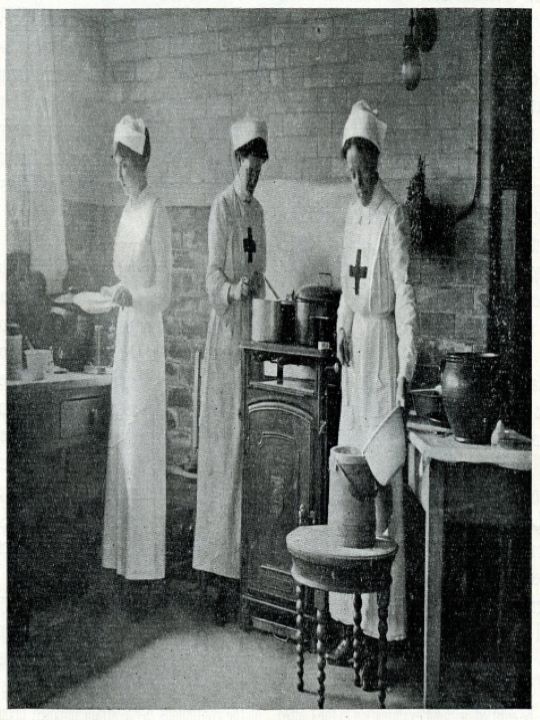

Then food shortages began in 1917. By this time the Red Cross was running temporary hospitals across the UK. Known as auxiliary hospitals, they treated injured servicemen – but they also had to feed them. We worked with the Ministry of Food and the War Office to ensure our patients had enough to eat.

Anne Auden was a Girl Guide who volunteered in the kitchens of Brookdale Red Cross hospital at Alderley Edge, Cheshire. For more than two years she popped in every week to roll up her sleeves and peel hundreds of potatoes.

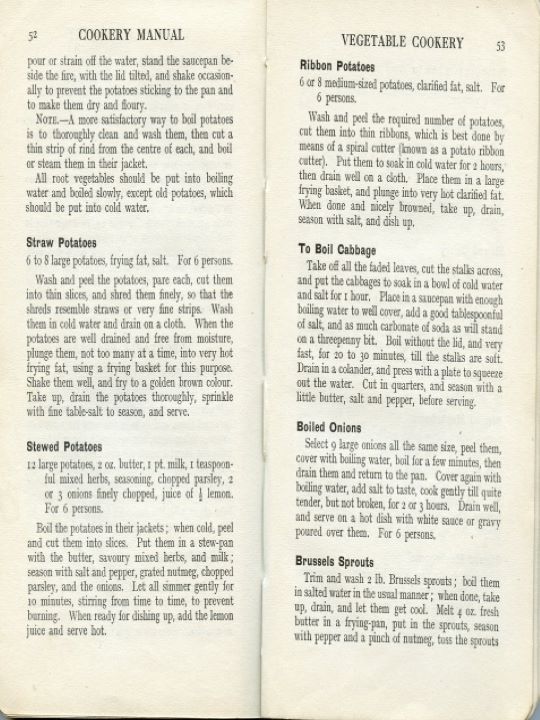

The Red Cross produced a cookery manual suggesting different ways to cook potatoes for patients (boil, stew, bake and fry in ‘ribbons or ‘straws’).

Many favourite foods – sugar, tea, meat, margarine, butter, cheese, fish, suet, golden syrup and jam – were all in limited supply. Bacon was off the menu as it was sold at double its pre-war price.

Breakfast in a Red Cross hospital was, therefore, porridge, cold boiled ham or fishcakes.

Dinner might be stewed tripe, boiled mutton, tapioca and savoury hash – no doubt made from some of Anne’s peeled potatoes.

For afters there were baked jam rolls, rhubarb and custard or bread and butter pudding. But some cooks struggled to get the recipes quite right…

One woman volunteered at a Red Cross hospital as a kitchen maid. In the topsy turvy world of the war, old class divides were often blurred. Women from rich families volunteered alongside working class women and girls.

This particular woman found herself serving as a kitchen maid to her own cook. But she did not share her cook’s expertise.

The Red Cross journal from 1916 reports that this woman “had been in trouble several times for her incompetence, and was passing a sleepless night of worry in connection with a lemon sponge.” It had not come right, and she knew what awaited her in the morning.

“Suddenly she had an idea. Rising from her bed, she crept to the kitchen… What exactly she did will never be known, but a message of thanks came down from the ward next day, with the comment that it was the best bread-and-butter pudding the patients had ever tasted.”