Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener

Technically, Earl Kitchener was not a Great War General.

By the time of World War One, the former Field Marshal was serving in the government role of Secretary of State for War.

Prior to this, Kitchener had enjoyed one of the most distinguished careers in the British Army. He had served across the world, including in Egypt, Sudan, India, and South Africa.

By 1909, Kitchener had been appointed Field Marshal: the highest rank in the British Army.

Kitchener was one of the most famous men in the British Empire. His reputation as one of the finest soldiers of his era won him great renown. He even served as commanding officer of 55,000 or so troops stationed in London for the Coronation of King George V, acting as one of the swords tasked with guarding the new monarch during the ceremony.

While storm clouds were gathering over Europe, Kitchener was serving as the British Agent and Consul-General in Egypt. Prime Minister Herbert Asquith recalled the former Field Marshal in August 1914 and quickly appointed him Secretary of State for War.

Interestingly, Kitchener was one of the few who foresaw a long war. It wouldn’t be all over by Christmas as others were predicting.

He may not have been commanding soldiers in the field but Kitchener’s influence over the British Army during the war’s early stages was significant.

The small professional British Expeditionary Force had been obliterated during the war’s earliest campaigns. It was up to Kitchener, who predicted Britain would have to use all its manpower “to the last million”, to recruit and train new British armies from scratch.

The solution was the creation of “New Armies” drafted from civilian conscripts.

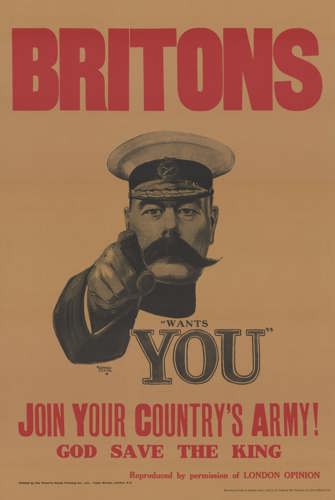

A wave of recruitment swept over the UK, spurred on by the now iconic “Lord Kitchener Wants You” poster designed by Alfred Leete.

Ordinary men and women signed up to either fight or support the war effort by the million.

While this allowed the British Empire to eventually field the largest armies it have wielded up to that stage, the “New Armies” were not without their drawbacks.

One problem was the Pals Battalions. These were units made up of young men from close local communities, be they towns, villages, or even streets.

They may have been good for morale and creating tight-knit bonds among soldiers, but Great War battlefields were brutal. Entire communities were tragically wiped out, sometimes within the space of several minutes.

Despite his enormous popularity with the public, Kitchener was not without criticism.

His running of the war effort came under fire following costly setbacks in the Dardanelles at Gallipoli and Loos, Belgium, and his handling of the munitions crisis. Gradually, his powers were reduced as others took up the burden of steering the course of the war, but he would be relied on for more diplomatic purposes.

In 1916, Kitchener was appointed to lead a delegation to Tsarist Russia to discuss armament supplies and support for the beleaguered Russian Army.

Together with France and Britain, Russia was one of the Entente Powers opposing Imperial Germany and its allies.

On the 5th of June 1916, Kitchener and his delegation left Scapa Flow naval base, Scotland, aboard HMS Hampshire. The ship and its passengers were headed for the Russian port of Arkhangelsk.

A misreading of weather reports, and intelligence indicating German submarine activity in the North Sea, spelled trouble for Hampshire from the off.

Conditions were harsh with Hampshire battling its way through a force 9 gale.

Suddenly, the steamship hit a mine laid by the newly launched U-75. Terrible damage was caused to the ship’s hull.

HMS Hampshire and 737 souls sank beneath the waves in rough seas west of the Orkney Islands. Earl Kitchener was one of Hampshire’s casualties. Only 12 men survived.

Eyewitnesses spotted Kitchener stoically standing on the ship’s quarterdeck for the 20 minutes it took Hampshire to sink. His body was never found.

Kitchener’s death rocked the British Empire. He was an exceptionally popular figure with the British public.

Upon hearing the news, one sergeant on the Western Front is recorded to have said: “Now we’ve lost the war.”

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, who would go on to become overall commander of the British Army, said: “How shall we get on without him?”

The Entente Powers would go on to win a costly victory, but the death of Kitchener was a massive blow to British morale.

Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, is commemorated on the Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton, UK.

Brigadier-General John Gough VC

Upon his death on 22nd February 1915, many in British high command were absolutely devastated when John Gough, Johnnie to his friends, passed away.

Gough was known as a fighting general, a man of great determination and grit but also tempered by realism and pragmatism.

His contemporary General Sir George Barrow described Gough as “a twentieth-century Chevalier Bayard”, referencing the 15th-century French knight Pierre Terrail. Terrail was known as a paragon of virtue and duty, something which, according to his friends and colleagues, Gough embodied.

Gough is famous for a remark made in November 1914 during a German attack.

“As he watched the enemy swarming over a low ridge one of his staff said the fight was decided,” historian Ian F.W. Beckett reports in his book Johnnie Gough V.C. “Gough turned with his eyes ablaze and exclaimed: ‘God will never let those devils win’”.

It’s said this quote completely summed up Gough’s character and attitude.

Further reinforcing his reputation was how Gough earned the Victoria Cross as a 31-year-old Major in the Rifle Brigade while serving in Somaliland.

On 22nd April 1903, Gough and his column of troops were attacked during the Third Somaliland expedition.

The British managed to conduct a solid defence and a fighting withdrawal but some men were left behind. Gough returned to the front to aid Captains William George Walker and George Murray Rolland in transporting a mortally wounded officer out of the firing line.

The wounded man was hoisted aboard a camel but was tragically, fatally wounded and died.

Rolland and Walker were given Victoria Crosses for their actions. Gough downplayed his role in the incident, but it was later revealed the then Major was also worthy of the Commonwealth’s highest military honour.

The Brigadier-General was often used as a sounding board for Field Marshal Douglas Haig, having travelled to France with I Corps of the BEF of which Haig was commander. He continued to be Haig’s number two when Haig took up greater command responsibilities as the war progressed.

Gough was considered a constructive yet not uncritical voice and had a good understanding of how Haig’s mind worked.

Many of his contemporaries believed that if Gough had gone on to command a division, he would have reached even higher rank. Indeed, he was poised to take command of one of Kitchener’s New Armies in February 1915.

Image: An armoured vehicle during the battle of Neuve Chapelle. John Gough was preparing for the battle before he was killed (© IWM Q 50727)

At this time, Gough was preparing for the attack on Neuve Chapelle. This action would result in small territorial gains for the Entente but incur just shy of 13,000 British and Indian casualties.

Gough was expected to take full command of one of the New Army divisions in March 1915. He would have achieved the rank of Major-General had this come to pass. Sadly, it was not to be.

On 20th February 1915, Gough headed to the front to visit the 2nd Battalion of the Rifle Brigade at Fauquissart, some 3 km north of Neuve Chappelle. His plan was to take lunch at the HQ Officers’ Mess there, before travelling back to the UK to take command of his new division.

While inspecting the line, Gough was hit in the chest by a ricocheting German bullet. The Brigadier-General was mortally wounded.

While it was not unusual for senior officers to get hit by sniper’s bullets, this particular incident was essentially down to massive bad luck. It’s thought that the bullet came from a single shot at a distance of 1,000 yards from the British front line, deep within German territory. It’s only by chance Gough was hit.

A field ambulance unit ferried Gough to Estaires, around 7 km from the frontline, where Gough succumbed to his wounds. He died on the morning of 22nd February 1915.

Gough was buried in the Estaires Communal Cemetery where he is commemorated to this day.

He was posthumously knighted and gazetted as a Knight Bachelor. This added to a long list of honours Gough had acquired over his highly distinguished military career.