At the beginning of 1914 the British Army had a reported strength of 710,000 men including reserves, of which around 80,000 were professional soldiers ready for war. By the end of the First World War almost 25 percent of the total male population of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland had joined up, over five million men. Of these, 2.67 million joined as volunteers and 2.77 million as conscripts (although some volunteered after conscription was introduced and would most likely have been conscripted anyway). Monthly recruiting rates for the army varied dramatically.

August 1914

At the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914, the British regular army numbered 247,432 serving officers and other ranks. This did not include reservists liable to be recalled to the colours upon general mobilization or the part-time volunteers of the Territorial Force. About one-third of the peace-time regulars were stationed in India and were not immediately available for service in Europe.

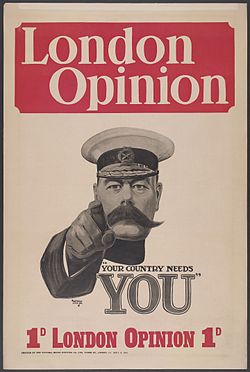

For a century British governmental policy and public opinion were against conscription for foreign wars. At the start of World War I the British Army consisted of six infantry divisions, one cavalry division in the United Kingdom formed shortly after the outbreak of the war, and four divisions located overseas. Fourteen Territorial Force divisions also existed, and 300,000 soldiers were in the Reserve Army. Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, considered the Territorial Force untrained and useless. He believed that the regular army must not be wasted in immediate battle, but instead used to help train a new army with 70 divisions—the size of the French and German armies—that he foresaw would be needed to fight a war lasting many years.

British Army medical categories

All recruits underwent a physical exam by Army medical officers to ascertain whether they would be suitable for military service which used a number and lettering system to categorise the health of each recruit. The following list are the categories used by the British Army in 1914.

- A Able to march, see to shoot, hear well and stand active service conditions.

- A1 Fit for dispatching overseas, as regards physical and mental health, and training

- A2 As A1, except for training

- A3 Returned Expeditionary Force men, ready except for physical condition

- A4 Men under 19 who would be A1 or A2 when aged 19

- B Free from serious organic diseases, able to stand service on lines of communication in France, or in garrisons in the tropics.

- B1 Able to march 5 miles, see to shoot with glasses, and hear well

- B2 Able to walk 5 miles, see and hear sufficiently for ordinary purposes

- B3 Only suitable for sedentary work

- C Free from serious organic diseases, able to stand service in garrisons at home.

- C1 Able to march 5 miles, see to shoot with glasses, and hear well

- C2 Able to walk 5 miles, see and hear sufficiently for ordinary purposes

- C3 Only suitable for sedentary work

- D Unfit but could be fit within 6 months.

- D1 Regular Royal Artillery (RA), Royal Engineers (RE), infantry in Command Depots

- D2 Regular RA, RE, infantry in Regimental Depots

- D3 Men in any depot or unit awaiting treatment

Examinations

Medical examinations were conducted in a very specific way according to War Office Instructions issued within the Regulations for the Medical Services of the Army, the Regulations for Recruiting, and the regulations for the Territorial Force on 1 August 1914. Basic requirements for a recruit was that their height, weight, chest measurement and age all correlated with a standard table. Medical examiners were given the discretion to decide a recruit’s “apparent age,” based on their appearance and physical stature, when they did not bring satisfactory documentation for proof of age.

Detailed body examinations would include looking for signs of sexually transmitted diseases, vaccination marks, lesions and rashes; the scrotum and anus would also be checked; there would be a stethoscopic examination of the heart, lung and abdomen; the hands and feet, elbows and knees would be studied for lameness, weakness and deformities; teeth (for loss and decay as being unable to chew because of poor oral hygiene was a common cause for failing the medical examination); eyesight and hearing.

Aside from the physical tests, examiners would also the note the intelligence, voice, and character of the recruit in response to questions they would ask him. This would be used to create a psychological profile that would help determine the fitness of the candidate.

Medical rejections and deferments

There were numerous medical reasons why recruits might be deemed unfit for service.

- Any signs or symptoms of tuberculosis

- Syphilis

- Any respiratory tract infections

- Palpitations or heart disease

- Generally impaired constitution

- Poor eyesight

- Hearing loss

- Stammering

- Tooth decay that inhibited eating

- Deformity of chest or joints

- Abnormal curvature of spine

- Intelligence

- Hernia

- Haemorrhoids

- Varicose veins or varicocele

- Chronic skin conditions

- Chronic ulcers

- Fistula

- Any other disease or physical defect that would prevent military service

Volunteer Army, 1914–15

In 1914, the British had about 5.5 million men of military age, with another 500,000 reaching the age of 18 each year. The first call was for 100,000 volunteers, made on 11 August, followed by another 100,000 on 28 August. By 12 September, almost half a million men had enlisted. At the end of October, 898,005 men had enlisted, of whom approximately 640,000 were non-TF enlistments. Around 250,000 underage boys also volunteered, either by lying about their age or giving false names. These were always rejected if the lie was discovered.

The standard Regular terms of service in the British Army were 7 years service with the colours, and 5 years in the reserve. To facilitate recruitment, supplementary Regular terms of service were announced by Army Order 296 dated 6 August 1914. Recruits to the New Army could serve for “three years or the duration of the war, whichever the longer”. These “General Service” terms were changed by Army Order 470 dated 7 November, simplified to “the duration of the war.” The recruit had the right to choose the regiment they joined.

To address the short-term need for trained men to replenish the originally deployed BEF units, supplementary Special Reserve terms of service were announced by Army Order 295 dated 6 August 1914, rescinded 7 November 1914. Ex-military men could reenlist for “one year or the duration of the war, whichever the longer”.

It was believed that former NCOs may be reticent to reenlist, having to serve as Privates. Given the need not only for former privates to enlist, but also experienced NCOs to play a part in the expansion of the army, Army Order 315 dated 17 August 1914 clarified matters. It states that ‘an ex-non-commissioned officer of the regular army who enlists [under the supplemental terms of service announced on 6 August 1914].. [will be] promoted forthwith to the rank held on discharge.

One early peculiarity was the formation of ‘pals battalions‘: groups of men from the same factory, football team, bank or similar, joining and fighting together. The idea was first suggested at a public meeting by Lord Derby. Within three days, he had enough volunteers for three battalions. Lord Kitchener gave official approval for the measure almost instantly and the response was impressive. Manchester raised nine specific pals battalions (plus three reserve battalions); one of the smallest was Accrington, in Lancashire, which raised one. One consequence of pals battalions was that a whole town could suffer a severe impact on its military-aged menfolk in a single day of fierce battle.

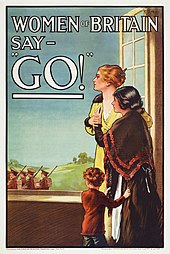

The women’s suffrage movement was sharply divided, the slight majority becoming very enthusiastic patriots and asking their members to give white feathers (the sign of the coward) in the streets to men who appeared to be of military age to shame them into service. After assaults became prevalent the Silver War Badge was issued to men who were not eligible or had been medically discharged.

The available pool was diminished by roughly 1.5 million men who were “starred”: kept in essential occupations. Almost 40 percent of the men who volunteered were rejected for medical reasons. Malnutrition was widespread in U.K. society; working class 15‑year‑olds had an average height of only 5 feet 2 inches (157 cm) while the upper class was 5 feet 6 inches (168 cm)

From the start Kitchener insisted that the British must build a massive army for a long war, arguing that the British were obliged to mobilise to the same extent as the French and Germans. His goal was 70 divisions, and the Adjutant General asked for 92,000 recruits per month, well above the number volunteering (see the graph). The obvious remedy was conscription, which was a hotly debated political issue. Many Liberals, including Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, were ideologically opposed to compulsion, but by 1915 they were wavering.

15 July 1915 the National Registration Act was passed by the British Government, exactly one month later there was a census of every citizen aged 15 to 65, approximately 29 million forms completed. A pink coloured registration card was issued to each registree, listing pertinent data. These records were ordered to be destroyed in 1921, yet some did survive, including the lately discovered forms of 2,409 women living in Cirencester, since transcribed and made publicly available. The Cabinet were given a strong warning in September 1915 in a paper presented by their only Labour member, Minister of Education Arthur Henderson. He argued many working men would strongly resist serving a nation in which they did not have a legitimate share in governing. They resented the idea of being dragooned to face possible death by a Parliament they had no part in electing—forty percent of men over 21 were denied the vote by the franchise and registration laws (until the Representation of the People Act of 1918). To them conscription was yet another theft of working men’s rights by rich capitalists. The only counter-argument the Government could offer was it was of absolute necessity. Workers must be convinced that there were too few volunteers to meet the need, meaning the loss of the war and the end of Britain! Army leaders should convince Union leaders by stating military facts. Henderson’s own son was killed in the war a year later.