I love watching Have I Got News For You every week it is on every Friday on BBC One. I think it is really good and very funny to it is only on for thirty minutes just half an hour and I really like it.

Weevles Updates Disabled Bloggers Team

Weevl Bloggers Corner

I love watching Have I Got News For You every week it is on every Friday on BBC One. I think it is really good and very funny to it is only on for thirty minutes just half an hour and I really like it.

I am looking forward to seeing Wwe RAW and Smackdown from this week and catching up with both of them later on this week because I haven’t even seen both of them yet.

These were the metro’s seven years ago in 2016 when I was twenty nine and then thirty years old when I was late twenties early thirties when I was younger. These were the old metro’s from back then back in those days and sometimes you can still see these kind of metro’s out and about at other Metro Station’s.

Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (19 May 1860 – 1 December 1952) was an Italian statesman, who served as the Prime Minister of Italy from October 1917 to June 1919. Orlando is best known for representing Italy in the 1919 Paris Peace Conference with his foreign minister Sidney Sonnino. He was also known as “Premier of Victory” for defeating the Central Powers along with the Entente in World War I. He was also the provisional President of the Chamber of Deputies between 1943 and 1945, and a member of the Constituent Assembly that changed the Italian form of government into a republic. Aside from his prominent political role, Orlando was a professor of law and is known for his writings on legal and judicial issues, which number over a hundred works.

Orlando was born in Palermo, Sicily. His father, a landed gentleman, delayed venturing out to register his son’s birth for fear of Giuseppe Garibaldi‘s Expedition of the Thousand, who had just stormed into Sicily on the first leg of their march to build an Italian nation.

Orlando taught law at the University of Palermo and was recognized as an eminent jurist. In 1897, he was elected in the Italian Chamber of Deputies (Italian: Camera dei Deputati) for the district of Partinico for which he was constantly reelected until 1925.[6] He aligned himself with Giovanni Giolitti, who was Prime Minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921.

A liberal, Orlando served in various roles as a minister. In 1903, he served as Minister of Education under Prime Minister Giolitti. In 1907, he was appointed Minister of Justice, a role he retained until 1909. He was re-appointed to the same ministry in November 1914 in the government of Antonio Salandra until his appointment as Minister of the Interior in June 1916 under Paolo Boselli.

After the Italian military disaster in World War I at Caporetto on 25 October 1917, which led to the fall of the Boselli government, Orlando became Prime Minister, and he continued in that role through the rest of the war. He had been a strong supporter of Italy’s entry in the war. He successfully led a patriotic national front government, the Unione Sacra, and reorganized the army. Orlando was encouraged in his support of the Allies because of secret incentives offered to Italy in the London Pact of 1915. Italy was promised significant territorial gains in Dalmatia.[5] Orlando’s first act as head of the government was to fire General Luigi Cadorna and appoint the well-respected General Armando Diaz in his place. He then reasserted civilian control over military affairs, which Cadorna had always resisted. His government instituted new policies that treated Italian troops less harshly and instilled a more efficient military system, which were enforced by Diaz. The Ministry for Military Assistance and War Pensions was established, soldiers received new life insurance policies to help their families in the case of their deaths, more funding was put into propaganda efforts aimed at glorifying the common soldier, and annual paid leave was increased from 15 to 25 days. On his own initiative Diaz also softened the harsh discipline practiced by Cadorna, increased rations, and adopted more modern military tactics which had been observed on the Western Front. All of these had the net effect of greatly increasing the formerly-crumbling army’s morale. Orlando’s government quickly proved popular among the general population and successfully reconstituted national morale after the disaster of Caporetto, with Orlando even publicly pledging to retreat to “my Sicily” if necessary and resist the Austrian invaders from there, though he was also assured that there would be no military collapse.

With the Austro-Hungarian offensive stopped by Diaz at the Second Battle of the Piave River, a lull in fighting ensued on the Italian front as both sides brought up their logistical elements. Orlando ordered an investigation into the causes of the defeat at Caporetto, which confirmed that it was the fault of the military leadership. While he continued to reform the military, he refused demands from both sides of the political aisle calling for mass trials of generals and ministers. The Italian front stabilized enough under his leadership that Italy was able to send hundreds of thousands of troops to the Western Front to buttress their allies while themselves preparing for a major offensive to knock Austria-Hungary out of the war. This offensive materialized in November 1918, the Italians launched the Battle of Vittorio Veneto and routed the Austro-Hungarians, a feat that coincided with the collapse of Austro-Hungarian Army and the end of the First World War on the Italian Front, as well as the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The fact that Italy recovered and ended up on the winning side in 1918 earned for Orlando the title “Premier of Victory.”

Orlando was one of the Big Four, the main Allied leaders and participants at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, along with U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau and Britain’s Prime Minister David Lloyd George. Although, as prime minister, he was the head of the Italian delegation, Orlando’s inability to speak English and his weak political position at home allowed the conservative foreign minister, the half-Welsh Sidney Sonnino, to play a dominant role.

Their differences proved to be disastrous during the negotiations. Orlando was prepared to renounce territorial claims for Dalmatia to annex Rijeka (or Fiume as the Italians called the town) — the principal seaport on the Adriatic Sea — while Sonnino was not prepared to give up Dalmatia. Italy ended up claiming both and received neither, running up against Wilson’s policy of national self-determination. Orlando supported the Racial Equality Proposal introduced by Japan at the conference.

Orlando dramatically left the conference early on April 24th 1919. He returned briefly the following month, but was forced to resign just days before the signing of the resultant Treaty of Versailles. The fact he was not a signatory to the treaty became a point of pride for him later in his life. French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau dubbed him “The Weeper,” and Orlando himself recalled proudly: “When … I knew they would not give us what we were entitled to … I writhed on the floor. I knocked my head against the wall. I cried. I wanted to die.”

His political position was seriously undermined by his failure to secure Italian interests at the Paris Peace Conference. Orlando resigned on 23 June 1919, following his inability to acquire Fiume for Italy in the peace settlement. The so-called “Mutilated victory” was one of the causes of the rising of Benito Mussolini. In December 1919, he was elected president of the Italian Chamber of Deputies, but never again served as prime minister.

When Benito Mussolini seized power in 1922, Orlando initially tactically supported him, but broke with him over the murder of Giacomo Matteotti in 1924. After that, he abandoned politics and resigned from the Chamber of Deputies in 1925, until 1935, when Mussolini’s march into Ethiopia stirred Orlando’s nationalism. He reappeared briefly in the political spotlight when he wrote Mussolini a supportive letter.

On 28 June 1914, Poincaré was at the Longchamps racetrack when he received news of the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. Poincaré was fascinated by the report but stayed on to watch the race.

In 1913, it had been announced that Poincaré would visit St. Petersburg in July 1914 to meet Tsar Nicholas II. Accompanied by Premier René Viviani, Poincaré went to Russia for the second time (but for the first time as president) to reinforce the Franco-Russian Alliance. On 15 July, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister, Count Leopold von Berchtold, used a back channel to informed foreign countries of Austria-Hungary‘s intention to present an ultimatum to Serbia. When Poincaré arrived in St. Petersburg on 20 July, the Russians told him by 21 July of the Austrian ultimatum and German support for Austria. Although Prime Minister Viviani was supposed to be in charge of French foreign policy, Poincaré promised the Tsar unconditional French military backing for Russia against Austria-Hungary and Germany. In his discussions with Nicholas II, Poincaré talked openly of winning an eventual war, not avoiding one. Later, he attempted to hide his role in the outbreak of military conflict and denied having promised Russia anything.

Poincaré arrived back in Paris on 29 July and at 7 am on 30 July, with Poincaré’s full approval, Viviani sent a telegram to Nicholas affirming that:

in the precautionary measures and defensive measures to which Russia believes herself obliged to resort, she should not immediately proceed to any measure which might offer Germany a pretext for a total or partial mobilization of her forces.

In his diary entry for the day, Poincaré wrote that the purpose of the message was not to prevent war from breaking out but to deny Germany a pretext and thereby obtain British support for the Franco-Russian alliance. He approved of Russian mobilization. A French covering force, five army corps strong, was deployed on the German border at 4:55 pm, as per normal premobilization procedure. Poincaré and Viviani demanded that the covering force be installed ten kilometers from the border, for the sole reason that France would look innocent in the eyes of Britain.A note was immediately sent to London to tell the British about the maneuver and gain their sympathy against Germany.

On 31 July the German ambassador in Paris, Count Wilhelm von Schoen, presented to Viviani a quasi-ultimatum warning that, if Russia did not end its mobilization within twelve hours, Germany would mobilize. Mobilization meant war. That same day, the Chief of the General Staff of the French Army, General Joseph Joffre appealed for general mobilization, falsely claiming that Germany had been secretly mobilizing for two or three days. Poincaré backed Joffre’s request. French general mobilization was decreed at 1600 hours on 1 August.On 1 August, Poincaré lied to Francis Bertie, the British ambassador to France, claiming that Russian mobilization had only been decreed after Austria’s.

After Germany declared war on France on 3 August, Poincaré said: “Never was a declaration of war received with such satisfaction”. He appeared before the National Assembly at 3 pm on 4 August to announce that France was now at war forming the doctrine of the union sacrée in which he announced that: “nothing will break the union sacrée in the face of the enemy. “Dans la guerre qui s’engage, la France […] sera héroïquement défendue par tous ses fils, dont rien ne brisera devant l’ennemi l’union sacrée” (“In the coming war, France will be heroically defended by all its sons, whose sacred union will not break in the face of the enemy”). During the meeting, Poincaré and Viviani were silent on Russia’s mobilization, claiming instead that Russia had been negotiating to the end.

Poincaré became increasingly sidelined after the accession to power of Georges Clemenceau as Prime Minister in 1917. He believed the Armistice happened too soon and that the French Army should have penetrated far deeper into Germany. At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, negotiating the Treaty of Versailles, he wanted France to wrest the Rhineland from Germany to put it under Allied military control.

Ferdinand Foch urged Poincaré to invoke his powers as laid down in the constitution and take over the negotiations of the treaty due to worries that Clemenceau was not achieving France’s aims. He did not, and when the French Cabinet approved of the terms which Clemenceau obtained, Poincaré considered resigning, although again he refrained.

When World War I began in July 1914, Italy was a partner in the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, but decided to remain neutral. However, a strong sentiment existed within the general population and political factions to go to war against Austria-Hungary, Italy’s historical enemy.

Annexing territory along the two countries’ frontier stretching from the Trentino region in the Alps eastward to Trieste at the northern end of the Adriatic Sea was a primary goal and would “liberate” Italian speaking populations from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, while uniting them with their cultural homeland. During the immediate pre-war years, Italy started aligning itself closer to the Entente powers, France and Great Britain, for military and economic support.

On April 26, 1915, Italy negotiated the secret Pact of London by which Great Britain and France promised to support Italy annexing the frontier lands in return for entering the war on the Entente side. On May 3, Italy resigned from the Triple Alliance and later declared war against Austria-Hungary at midnight on May 23.

At the beginning of the war, the Italian army boasted less than 300,000 men, but mobilization greatly increased its size to more than 5 million by the war’s end in November 1918. Approximately 460,000 were killed and 955,000 were wounded in the conflict.

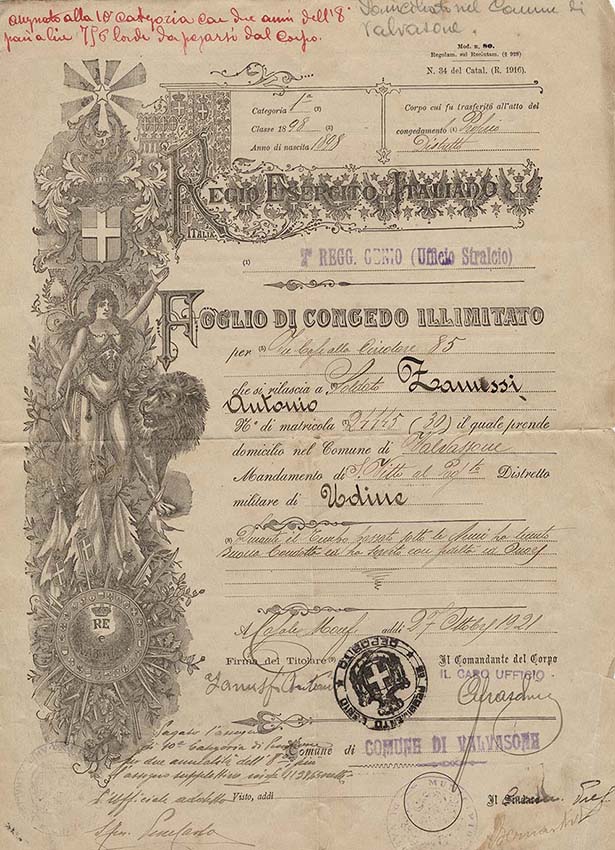

This service record is for Antonio Zanussi, who served in the 2nd Engineers. Zanussi was conscripted in February 1917, entered the service March 17, 1917 and fought in the campaign against Austria-Hungary in 1917-18. The record states that Zanussi served with good conduct and faithful service.

This postcard honors the memory of Captain Giuseppe Tagliamonte, commander of the 10th Infantry Company at the battle of Selz along the Italian/Austro-Hungarian frontier in northeastern Italy during the 2nd Isonzo Offensive. Tagliamonte was killed during the battle on July 19, 1915 and was awarded the Gold Medal of Military Valor, among Italy’s highest military decorations.

Do you feel stuck in a rut because you find daily living skills a challenge, then look no further than Wise Group. For further information contact 07990 540 794.